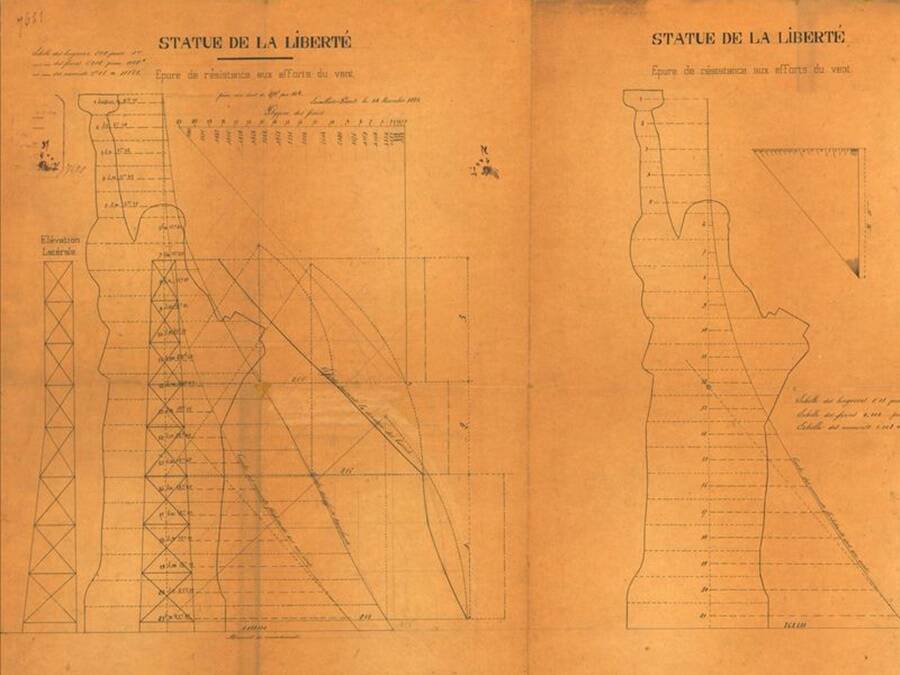

These newly-uncovered drawings show that late alterations were made to Lady Liberty's raised arm.

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique MapsNewly found sketches from Gustave Eiffel’s workshop show a different design for the Statue of Liberty.

In 2018, map dealer Barry Lawrence Ruderman procured a folder containing materials that once belonged to famed architect Gustave Eiffel in an auction in Paris.

Eiffel — best known for his eponymous tower structure in Paris — was commissioned to construct the skeleton of the Statue of Liberty by designer Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi.

Ruderman’s purchase was supposed to be blueprint copies related to the statue’s construction. But little did he know that the folder would also contain never-before-seen original sketches of the statue’s construction, revealing late changes that had been made to its structural design.

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the original drawings that were inside Ruderman’s purchased folder had been hidden in plain sight because they were stuck folded together.

The true value of the documents was finally revealed after they were sent to a conservator who placed the papers in a humidified chamber to soften their grip.

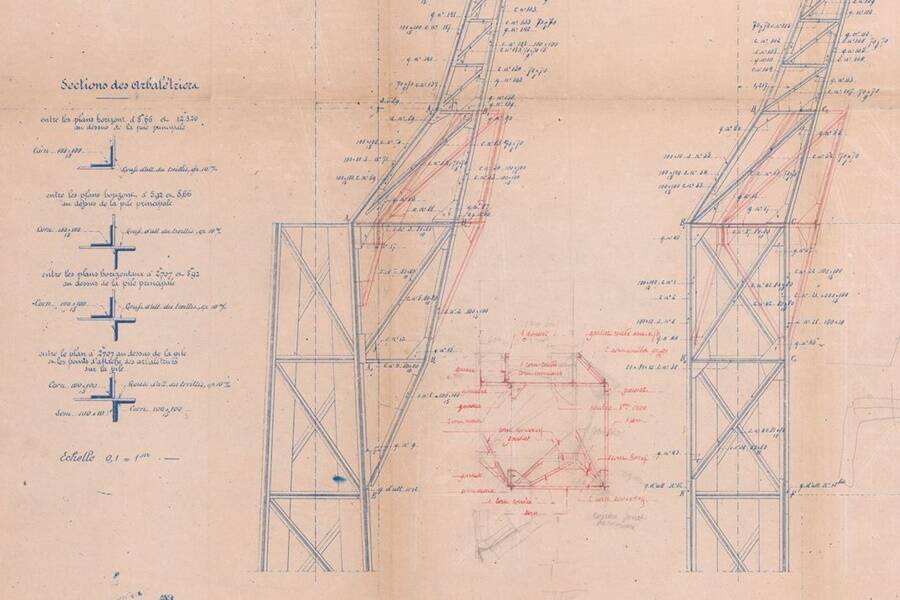

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique MapsRed ink markings were made to the original blue ink drawings as if to make adjustments to the statue’s arm.

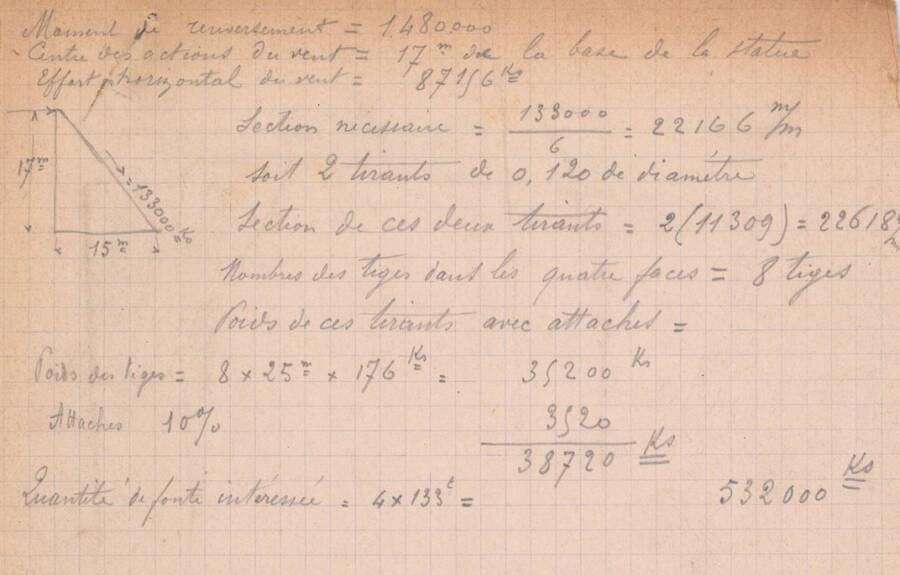

The separated documents were more than Ruderman could have envisioned: 22 original engineering drawings of the Statue of Liberty, including handwritten annotations and calculations inside its margins.

“To find the drawings from which all the blueprints were made, that’s just as good as it could get,” said Alex Clausen, the director of Ruderman’s gallery.

The newly discovered drawings depict multiple angle views of Eiffel’s designs for the iron trusswork to support the enormous statue. The papers also feature closeups of many key elements of the statue, like the hardware needed to attach the statue to its concrete base.

On the margin of the drawings appear handwritten calculations which seem to have been adjustments to the original measurements planned out by Eiffel.

Most notably, several drawings show Lady Liberty’s arm with a bulkier shoulder, holding the torch much higher than was later built. The bulkier drawings offer a sturdy structural foundation to support the raised arm of the statue.

But one of these drawings is hand-marked in red ink, drawing an outline that has the statue’s arm tilted more outward, as Bartholdi wanted.

Barry Lawrence Ruderman Antique MapsA page of handwritten calculations estimating forces on the statue due to winds in the gusty harbor.

“It looks like somebody is trying to figure out how to change the angle of the arm without wrecking the support,” said historian Edward Berenson who authored the book The Statue Of Liberty: A Transatlantic Story. “This could be evidence for a change in the angle that we ended up with in the real Statue of Liberty.”

Drawing up a sturdy foundation for the massive 151-foot tall Statue of Liberty was no easy feat. In addition to its height, the statue’s facade was made out of copper as thin as two stacked pennies.

It needed to withstand the forceful winds ripping through New York’s harbor and the potential for corrosion from the surrounding saltwater.

To fortify the foundation, Eiffel installed asbestos insulation between the iron skeleton and copper exterior. He also devised an interior skeleton made out of wrought iron designed with a network of springs to absorb the force of the winds.

Eiffel’s ingenious design allowed the structure to maintain its integrity up until the statue’s restoration project in the 1980s. The statue now sways up to three inches during a 50 mile per hour wind while its torch sways up to six inches.

More astonishingly, the date on the sketches and pages, July 28, 1882, suggests that the change to the statue’s arm design — depicted in handwritten red ink on the schematics — was likely a last-minute addition since most of the statue had already been built at that point.

Akerberg/NY Daily News Archive via Getty ImagesA crowd gathers around a model of the Statue of Liberty in Times Square.

Historians have long suspected that Eiffel’s initial designs had intended for a more sound foundation to support Lady Liberty’s raised arm. But the lack of material evidence representing the collaboration between Eiffel and Bartholdi meant that hypothesis could never be supported — until now.

However, historians still question how a last-minute change to such a massive construction project was able to bypass Eiffel’s approval.

One possibility is that Eiffel may have been too busy with his other projects at that stage of Lady Liberty’s construction and handed it over to his assistants to oversee the project’s completion.

“That may be one reason why Bartholdi decided he could make modifications, because he knew that Eiffel was not totally hands-on,” said Berenson. “Bartholdi played down Eiffel’s contributions because he was kind of an egotistical guy.”

After nearly a decade of construction and a grueling transatlantic journey between France and the United States and a two-year reassemblage, the Statue of Liberty was finally dedicated on Oct. 28, 1886. It still stands tall today.

Next, meet Emma Lazarus, the courageous Jewish poet behind the Statue of Liberty’s famous inscription, and take a look at 44 poignant photos of Ellis Island immigrants that convey the hope and hardships of coming to America.