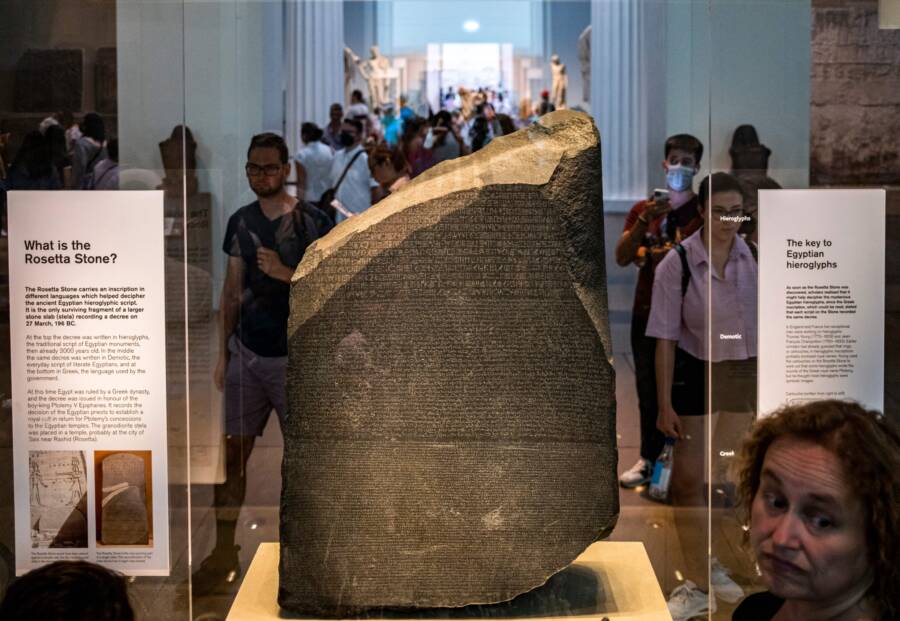

Now on display in the British Museum, the Rosetta Stone is a granite tablet from 196 B.C.E. inscribed with a decree in Egyptian hieroglyphics, ancient Greek, and Demotic script.

AMIR MAKAR/AFP via Getty ImagesThe Rosetta Stone is currently housed at the British Museum, as seen there in July 2022.

As French troops prepared to face Ottoman forces in Rosetta, Egypt, in July 1799, they stumbled upon a chunk of carved stone. Stuck into the wall of a fort, it displayed three languages — and soon proved to be the key to deciphering the long-lost language of Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Inscribed in 196 B.C.E., the so-called Rosetta Stone was acquired by the British in the early 19th century and has been held for centuries in the storied British Museum. But its future placement is more controversial.

Stumbling Upon The Rosetta Stone

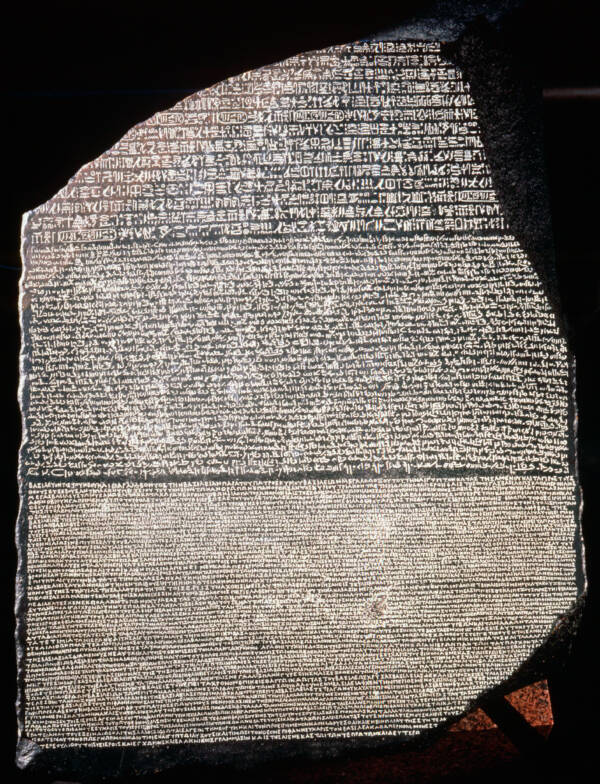

Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty ImagesThe Rosetta Stone is inscribed with three languages, Egyptian hieroglyphics, the simpler Egyptian Demotic script, and ancient Greek.

No one set out to find the Rosetta Stone. Indeed, on July 19, 1799, French troops were merely fortifying an old fort in Rashid, or Rosetta, Egypt, to prepare for a looming battle with the Ottoman army. According to the British Museum, they were digging foundations when they came across the mysterious relic.

The stone, filled with detailed inscriptions, was about 44 inches tall, 30 inches wide, and weighed around 1,680 pounds. As History noted, Napoleon Bonaparte had instructed his soldiers to look out for Egyptian artifacts to bring back to France, so the stone’s potential importance was not lost on the French soldiers who stumbled across it.

“Among the fortification works … carried out on the old Rashid fort (now called Fort Julien) on the left bank of the Nile … a beautiful black granite stone, of fine grain and hard as a hammer, was excavated,” the Courier de l’Egypte announced at the time. “Only one side is polished, and on it are three distinct inscriptions, separated into three parallel strips.”

Pierre-François Bouchard, the soldier who’d overseen the work at the fort in Rosetta, transported the stone to Cairo. But the stone didn’t stay in French hands. After the British defeated the French in the Napoleonic War in 1801, they took possession of it.

Then, the race to translate the Rosetta Stone began.

The Quest To Understand The Ancient Stone

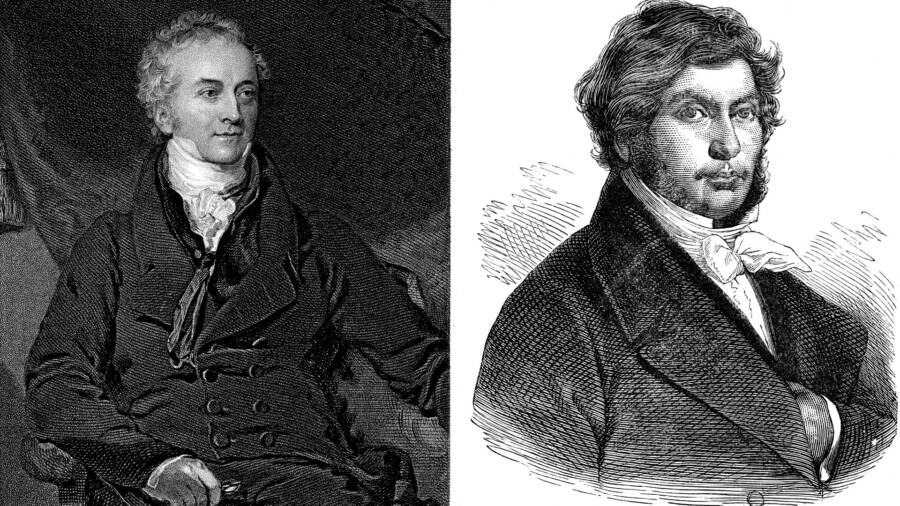

Oxford Science Archive/Print Collector/Getty Images and Ann Ronan Pictures/Print Collector/Getty ImagesThomas Young, left, and Jean-Francois Champollion, right, two of the main scholars who cracked the code of the Rosetta Stone.

Though the use of hieroglyphics had died out after the fourth century due to the rise of Christianity, scholars of the 19th century could still read ancient Greek, which was one of the three languages found carved into the stone.

They learned that the stone contained a religious decree that affirmed the loyalty of Greek priests to Ptolemy V Epiphanes, a pharoah who’d taken power in 204 B.C.E.

The stone also gave instructions for copies of it to be placed in temples throughout Egypt. And, significantly, it contained a note saying that the same message had been inscribed in the following three languages: hieroglyphics used for official religious business, the more informal Demotic script, and the administrative language of ancient Greek.

Once scholars had managed to translate the ancient Greek, they turned their focus to understanding the hieroglyphics. This work fell largely to two men, British scientist Thomas Young, and French linguist Jean-Francois Champollion.

According to History, Young started to examine the Rosetta stone in 1814. He found that some of the hieroglyphics were contained in an oval, which he called cartouches, and that these spelled out royal names like Ptolemy. But as the British Museum noted, Young was ultimately unable to figure out how the signs conveyed meaning.

That task fell to Champollion, who started studying the Rosetta Stone in 1822. Champollion had extensive knowledge about Egypt and even understood the Coptic language, which had descended from ancient Egyptian. He found that the hieroglyphics contained Coptic sounds.

“I’ve got it!” Champollion allegedly cried, per National Geographic, when he made his breakthrough. Then, the French linguist fell into a dead faint and didn’t recover for five days.

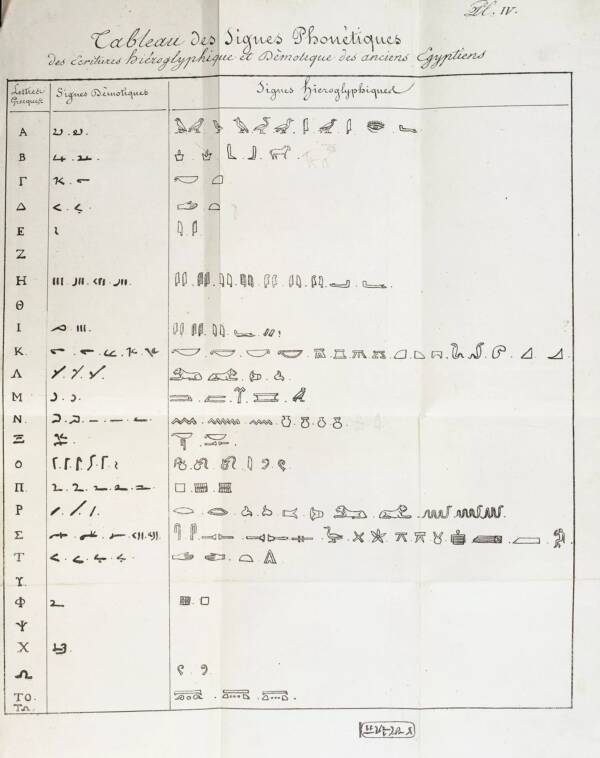

British MuseumChampollion’s translation from ancient Greek to Demotic script to hieroglyphics.

Champollion’s discovery, and further works on hieroglyphics, made him the so-called “Father of Egyptology.” According to The Irish Times, he figured out that the symbols fell into four categories. They were either pictograms (describing objects), ideograms (describing abstract ideas), used phonetically, or used as a derivative, which could alter the meaning of a group of symbols.

Thanks to him, the language of hieroglyphics had been revived — and allowed archaeologists to understand inscriptions left on temples and tombs all over Egypt.

But the story of the Rosetta Stone doesn’t end there. Indeed, it continues into modern times, as Egypt and the United Kingdom debate over which country has the right to display this pivotal historical artifact.

The Controversy Around The Rosetta Stone Today

Fox Photos/Getty ImagesVisitors to the British Museum examine the Rosetta Stone in 1932.

According to the British Museum, the institution acquired the Rosetta Stone in 1802, shortly after the British had won the artifact from the French. Because the museum couldn’t hold the stone’s great weight, a new gallery was constructed to display it and other artifacts.

Ever since — aside from a two-year period during World War I — the Rosetta Stone has remained in British hands. On display at the British Museum, the artifact attracts some six million visitors per year.

But some Egyptians think that it’s time for the United Kingdom to return the stone to Egypt. According to Art News, former Egyptian antiquities minister Zahi Hawass has been pushing for the return of the Rosetta Stone from the U.K., as well as a bust of Queen Nefertiti from Germany, and a sculpted Zodiac ceiling from France.

“I believe those three items are unique and their home should be in Egypt. We collected all the evidence that proves that these three items are stolen from Egypt,” Hawass told The National.

He added, “The Rosetta Stone is the icon of Egyptian identity. The British Museum has no right to show this artifact to the public.”

Hawass claims that he’s appealed to the British Museum for the return of the Rosetta Stone since 2003 and that he plans to present a petition signed by Egyptian academics in October 2022. The British Museum, for its part, claims that Egypt has made no such formal request for the Rosetta Stone.

But given that museums around the world have repatriated objects in recent years, it seems possible that the Rosetta Stone may find its way back to Egypt eventually. For now, there’s a replica of the famous artifact at the Cairo Museum of Egyptian Antiquities.

And some think that the replica may be enough. Eltayeb Abbas, the head of archaeology at the Grand Egyptian Museum, says that as much as he’d like to have the artifact back, he doubts that the real-life Rosetta Stone will ever return to Egypt.

“If we are going to talk seriously — these objects will never come to Egypt,” Abbas told Evening Standard. “But being there in Berlin or London in the British Museum — that is good propaganda for Egypt. It’s a good advert.”

As such, the story of the Rosetta Stone is ongoing. Whether the artifact will remain in the United Kingdom or return to Egypt is unknown. But the significance of this carved stone is indisputable. Thanks to linguists like Champollion, it provided the key to understanding a lost language.

After reading about the Rosetta Stone, discover the story of Cleopatra’s death. Or, look through these fascinating facts about ancient Egypt.