Determined to prove that ancient peoples could have made contact with one another across the oceans, Norwegian ethnographer Thor Heyerdahl built a raft out of balsa logs and hemp rope — and successfully used it to cross the Pacific Ocean in 1947.

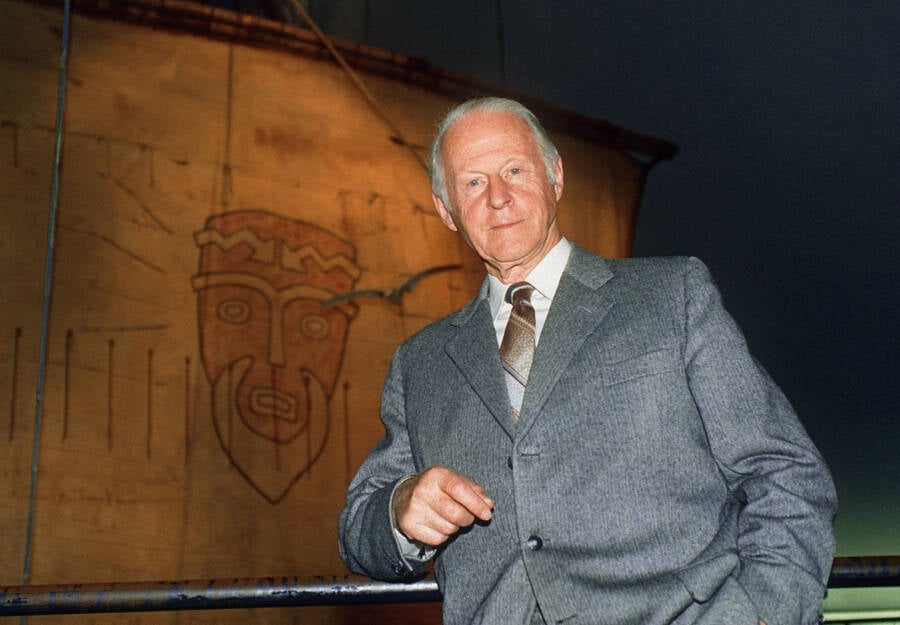

ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty ImagesThor Heyerdahl with artifacts from Easter Island.1957.

When Thor Heyerdahl looked at the ancient world, he saw patterns. Artifacts, language, and cultural activities like pyramid building in disparate cultures convinced Heyerdahl that ancient people might have interacted with one another across oceans. And so he set out to prove it.

Over 30 years, Heyerdahl completed several transoceanic voyages to prove that ancient people could have influenced each other. Traveling by simple boat, he and his small team traversed thousands of nautical miles to demonstrate that such travel could have been possible in ancient times, too.

In the end, Heyerdahl’s voyages didn’t prove anything definitive, but they did suggest that ancient people could have embarked on similar ones. And though Heyerdahl’s beliefs were largely dismissed in his day, some modern-day scholars see what he was seeing.

How Thor Heyerdahl Became An Adventurer

Born on October 6, 1914, in Larvik, Norway, Thor Heyerdahl developed a fascination with the world at a young age. His mother, Alison, was the head of the Larvik area museums association and inspired her son’s interest in nature and animals.

In pursuit of that interest, Heyerdahl enrolled in the University of Oslo to study zoology and geography in 1933. But Heyerdahl’s academic career was short-lived. Restless and eager to see the world, he dropped out in 1936 and went to live in Polynesia with his new wife, Liv Coucheron Torp.

The Kon-Tiki MuseumThor Heyerdahl with his first wife, Liv Coucheron Torp, during their stay in French Polynesia.

There, living on Fatu-Hiva in the Marquesas Islands of French Polynesia, Heyerdahl began to wonder how early people had settled there. According to The New York Times, he concluded that they had probably ridden eastern ocean currents to navigate from South America.

History Daily reported that Heyerdahl came to this conclusion for a couple of reasons. The first being that Polynesians ate South American plants like sweet potatoes and seemed to share certain myths and legends with Peruvians. Heyerdahl believed that this wasn’t a coincidence, but rather evidence that the ancient civilizations had somehow interacted with each other.

He began to develop his ideas as the years passed, though his pursuit of answers was briefly put on hold during World War II. Then, Heyerdahl served in the Free Norwegian armed forces in the north of the country. But once the war ended, he turned back to his research.

There was just one problem — most academics didn’t support Heyerdahl’s theory. They argued that ancient people had migrated to Polynesian from the west, from Asia, and that ancient South Americans would not have been able to cross the ocean.

So, Thor Heyerdahl decided to prove that such a crossing was possible. In 1947, he prepared to sail from Peru to French Polynesia in a simple boat.

The Many Voyages Of Thor Heyerdahl

Keystone/Getty ImagesThor Heyerdahl and his Kon-Tiki raft in 1947.

On April 28, 1947, Thor Heyerdahl set out to prove his theory that the islands in Polynesia could have been contacted by ancient South Americans. Along with five others, Heyerdahl climbed onto a raft made of balsa logs tied together with hemp rope. The raft was dubbed Kon-Tiki after the Incan sun god, Viracocha, for whom “Kon-Tiki” was said to be an old name, and the expedition started to sail east.

“The Kon-Tiki expedition opened my eyes to what the ocean really is,” Heyerdahl wrote of the journey in his 1950 book Kon-Tiki. “It is a conveyor and not an isolator.”

After 101 days at sea, Heyerdahl and his crew landed successfully in the French Polynesian atoll, Raroia. With that, Heyerdahl had proven that it was possible for ancient people to have made the same 4,300-mile voyage by simple watercraft.

But Thor Heyerdahl didn’t stop there. In addition to expeditions in the Galápagos Islands and Easter Island — both of which Heyerdahl believed had been settled by South Americans — Heyerdahl also began to consider other possible transoceanic connections between ancient cultures.

In the late 1960s, he turned his attention to Egypt. Heyerdahl was entranced by similarities between ancient Egyptians and ancient Mexicans, like the Egyptian construction of the pyramids and the ruins of Chichén Itzá in Mexico.

In 1969, he set off on a transatlantic voyage from Morocco to Barbados in a reed boat called Ra to prove scholars, who doubted that ancient Egyptians could have made such a voyage, wrong.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThor Heyerdahl, in blue, oversees the construction of his Ra ship in front of the Egyptian pyramids.

Unlike Kon-Tiki, however, the first Ra voyage was a failure. Heyerdahl’s vessel floundered 600 miles from Barbados after sailing for 3,000 miles. Determined to prove his theory, Heyerdahl made the voyage again in 1970 with Ra II. After 57 days at sea, the reed boat successfully made the 4,000-mile voyage from Morocco to Barbados.

“I still don’t know [what exactly this proves],” Heyerdahl wrote, as reported by The New York Times.

“I have no theory but that a reed boat is seaworthy and the Atlantic is a conveyer. But I would hereafter consider it barely short of a miracle if the multitude of active maritime expeditions during the millennia of antiquity never happened to… be swept off course while struggling to avoid shipwreck in the dreaded currents around Cape Juby.”

Seven years later, Thor Heyerdahl made yet another voyage to explore possible connections between ancient cultures in the Middle East. After building a reed boat called Tigris, Heyerdahl and his crew sailed down the Tigris River to prove that ancient Sumerians could have influenced cultures in present-day Egypt and India.

That voyage, however, came to an unexpected conclusion when Heyerdahl and his crew reached Ethiopia. When officials refused to allow them to land because of ongoing strife, Heyerdahl burned his boat.

“Our planet is bigger than the reed bundles that have carried us across the seas,” he and his crew wrote in a letter to the U.N., “and yet small enough to run the same risks unless those of us still alive open our eyes and minds to the desperate need of intelligent collaboration to save ourselves and our common civilization from what we are about to convert into a sinking ship.”

By then, with Heyerdahl in his 60s, the adventurer decided to retire from his sea-faring life. But he felt that he’d left a significant impact and asked important questions about how early civilizations might have interacted with each other.

“I have proved that all the ancient pre-European civilizations could have intercommunicated across oceans with the primitive vessels they had at their disposal,” he said, according to The New York Times. “I feel that the burden of proof now rests with those who claim the oceans were necessarily a factor in isolating civilizations.”

But did Thor Heyerdahl actually prove his naysayers wrong?

The Legacy Of The Norwegian Explorer

AGNETE BRUN/AFP via Getty ImagesThor Heyerdahl in 1990 in Oslo, Norway.

By the time Thor Heyerdahl died on April 18, 2002, most scholars remained convinced that Polynesia had been settled by people migrating from the west — not the east, as Heyerdahl suggested.

Indeed, recent genetic studies suggest that Polynesia was first settled by people who came from Asia, probably from Taiwain or the Philippines.

However, according to Science Norway, other genetic studies have suggested that Heyerdahl was onto something — and the ancient Polynesians did in fact have South American DNA.

Meanwhile, other modern scholars argue that it was the other way around, and that people sailing from Polynesia influenced ancient people in South America. After all, many island cultures in the Pacific have long-standing traditions of navigating to other islands by simple watercraft.

For now, it’s a question that merits more exploration, discussion, and tests. But that’s all Thor Heyerdahl ever really wanted, anyway.

“I have challenged a lot of old dogma, and this has stimulated a lot of discussion,” Heyerdahl said before he died. “And in science you need discussion.”

After reading about the adventures of Thor Heyerdahl, look through these fascinating maps of the ancient world. Or, see how researchers proved that Vikings landed at Lanse-aux-Meadows in Canada 500 years before Christopher Colombus.