Tiberius ruled as Rome's second emperor from 14 to 37 C.E., but he wasn't as well-liked as his predecessor Augustus, and he spent much of his reign in seclusion on the island of Capri.

The British Library/Flickr Creative CommonsThe Roman emperor Tiberius was an acclaimed military commander, launching his first campaign at 22 years old.

Although Tiberius began his reign as the second emperor of Rome as a competent, acclaimed military commander, his time as one of the most powerful leaders in the world ended in estrangement and self-exile.

When Tiberius was a child, his mother divorced his father and married Augustus, the man who became Rome’s first emperor. From an early age, Tiberius was trained to be a leader, studying military tactics as well as rhetoric and diplomacy. When Augustus had no biological sons — and all of his grandsons died young or were exiled — he adopted Tiberius as his own and named him his heir.

After a series of successful military campaigns, Tiberius became emperor in 14 C.E. upon the death of Augustus. He strengthened Rome’s navy and filled the treasury, but he also enacted several unpopular policies, such as halting the funding of gladiatorial games. What’s more, Tiberius wasn’t nearly as charismatic as his predecessor, so he fell out of favor with both the Senate and the Roman people.

Roman emperor Tiberius spent the final decades of his reign in self-isolation on the island of Capri, where he delegated much of the actual governing of the empire to others. By the time he died in 37 C.E., he’d established a reputation of tyranny and debauchery — but he may not have entirely deserved it.

Growing Up In The Shadow Of Augustus

Following the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C.E., the future of Roman rule was uncertain. Caesar had named his 18-year-old great-nephew Augustus, also known as Octavian, as his heir, but many citizens disagreed with the dictator’s decision.

Public DomainThe Death of Julius Caesar by Vincenzo Camuccini, 1806.

In the resulting power struggle, Augustus eliminated many of his rivals, including Caesar’s former protégé, Mark Antony. Amid the chaos, Tiberius’ father, Tiberius Claudius Nero, had pledged his support to Antony. With Antony defeated, however, Tiberius’ family became fugitives.

By the time Tiberius was three, his family had been granted amnesty, and they returned to Rome. His mother, Livia Drusilla, was pregnant with her second son at the time, but she caught the attention of Augustus. He found himself entranced by her, and he divorced his own wife and forced Livia to leave her husband so that he could take her as his own.

Tiberius and his father were cast aside, and when his younger brother Drusus was born, he joined them. This lasted for six years until the elder Tiberius died and his two sons were sent to live with their mother and Augustus.

Jonathan Larsen / Diadem Images / Alamy Stock PhotoA statue of Augustus in Rome.

Tiberius and Drusus grew up alongside Augustus’ daughter Julia and his nephew Marcellus. The three boys were each trained as potential successors to Augustus’ throne, as there was no clear law to determine which of them would be the heir. Tiberius proved to be a quick learner, and he began dining with kings and overseeing religious ceremonies before he was 14. However, he struggled to convey his ideas well, and he was not known to be handsome.

When Tiberius was 15, Augustus took him and Marcellus to Gaul to inspect outposts, where each boy learned a great deal about military fortifications. Upon their return home, Augustus declared that Marcellus and Julia would be married, effectively confirming that Marcellus would be the next emperor. However, this would not come to pass — and Tiberius soon found that his life was no longer in his control.

Death, Adultery, And Tiberius’ Rise To Power

Public DomainTiberius served as the second emperor of Rome from 14 C.E. to 37 C.E.

Around 19 B.C.E., Tiberius wed a woman named Vipsania Agrippina, and their marriage was a rare love match. Around the same time, the future emperor led his first military command at the age of 22. His success brought him great acclaim, and he soon became a respected leader who was known for the care he showed toward his men.

Everything was going well for Tiberius. He’d found a wife he loved, and he was poised to have a long and triumphant military career. Then, his luck started to turn when his younger brother, Drusus, died after falling from a horse in 9 B.C.E. Marcellus had also perished from an illness by this point, leaving Tiberius as the only remaining option from Augustus’ original three potential successors. However, Julia had remarried after Marcellus’ death and birthed sons who were related to Augustus by blood and would thus likely become his heirs instead.

When Julia’s second husband died as well, though, Augustus was determined to marry her off once more — this time to Tiberius. He had no choice. He was forced to divorce his beloved wife, Vipsania.

The marriage of Tiberius and Julia was no fairytale romance. She soon grew tired of her new husband, and he became resentful of his new wife. Julia sought the company of other men, which put Tiberius in a moral conundrum. By the law of Augustus himself, a husband was required to denounce a wife who committed adultery. Yet to inform the emperor of his own daughter’s infidelity would no doubt cause him great shame.

Public DomainA 19th-century painting by Russian artist Pavel Svedomsky of Julia in exile after Augustus learned of her infidelity to Tiberius.

So, Tiberius asked for fighting commands that would take him away from Rome, and his request was granted. He spent most of his time outside of the city, but during one visit back home, he happened to encounter Vipsania, who had remarried. Overcome with grief, Tiberius allegedly wept and followed her through the streets. In response, Augustus demanded that Tiberius never see Vipsania again.

Although the future Roman emperor Tiberius was awarded more and more power, he remained aggrieved by the path his life had taken. In 6 B.C.E., he essentially retired and went into self-imposed exile on the island of Rhodes. During that period, something changed within Tiberius. He grew angry and bitter.

While Tiberius was gone, his mother secured proof of Julia’s infidelity and presented it to Augustus. The emperor could not find it in his heart to execute his own daughter, as his law decreed, but he did exile her. Then, over the next several years, Julia’s sons either died or were exiled themselves. By 4 C.E., Augustus had no other option than to make Tiberius his heir, and he adopted him as his own son.

Ten years later, on August 19, 14 C.E., Augustus died, and Tiberius became the second emperor of Rome.

The Reign Of Roman Emperor Tiberius

For the most part, Tiberius’ early rule was largely a continuation of Augustus’. Under the new emperor, Rome was strong and secure, and it functioned efficiently. Moreover, Tiberius cast aside some of the more pompous traditions of Augustus and Caesar before him — notably, he refused to let a month be named for him. He also stopped funding gladiatorial games, a policy that was unpopular with the Roman people.

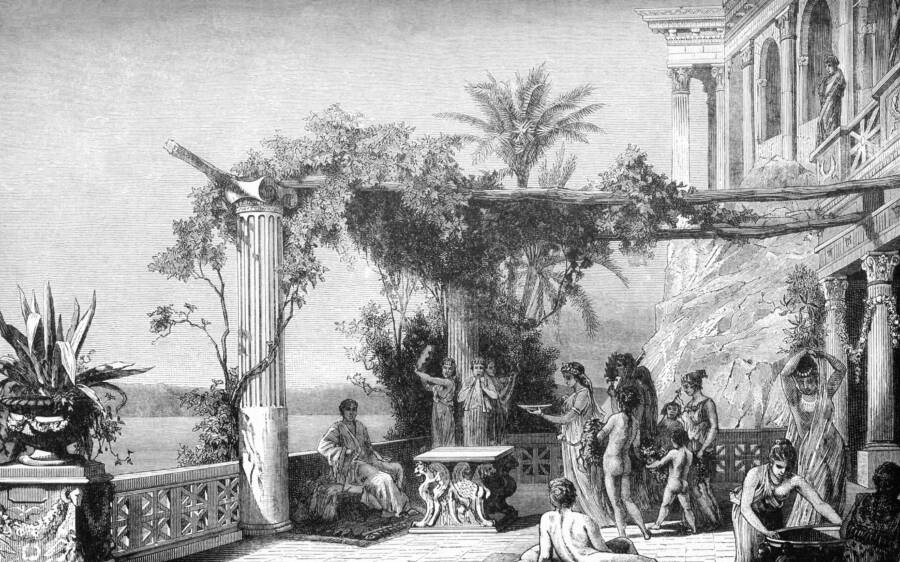

Ivy Close Images / Alamy Stock PhotoTiberius enjoyed the island of Capri and spent much of his time there, especially in his later years.

However, in 23 C.E., tragedy struck. Tiberius’ son Drusus, named after his late brother, died. Soon, the emperor began to withdraw into himself and focus less on the empire. He delegated most of the governing work to Sejanus, a member of his Praetorian Guard, and he essentially became an emperor in name only.

While Sejanus effectively ruled Rome in Tiberius’ stead, the emperor left the city for the island of Capri, where he remained until his death. There, over the course of a decade, Tiberius established his controversial legacy.

He built several villas across Capri, many of which reportedly featured dungeons and torture chambers. Disturbing rumors about abusing women and sexually assaulting children began to spread about the emperor, some of which were later recorded by the historian Suetonius:

“He acquired a reputation for still grosser depravities that one can hardly bear to tell or be told, let alone believe… The story is also told that once at a sacrifice, attracted by the acolyte’s beauty, he lost control of himself and, hardly waiting for the ceremony to end, rushed him off and debauched him and his brother, the flute-player, too; and subsequently, when they complained of the assault, he had their legs broken.”

These accusations largely remain unfounded, but they contributed to the emperor’s reputation for cruelty and depravity. However, even if they were true, Tiberius didn’t lose his mind entirely. He soon became aware that he had given Sejanus almost complete power and began enacting a plan to take that power back. He smuggled a letter to the Roman Senate denouncing Sejanus and calling for his execution. The Senate complied.

ALLTRAVEL / Alamy Stock PhotoA statue of Tiberius on Monte Solarno on Capri.

With Sejanus gone, Tiberius’ concern shifted to the matter of succession. With few living heirs — and many undesirables among them — he settled on what he considered the least offensive option: a young man named Gaius Caesar Germanicus, more commonly known by his nickname, Caligula. If Tiberius was considered depraved in his time, Caligula would eventually usurp that legacy.

The reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius came to a sudden end in the spring of 37 C.E. when he was 78 years old. One version of his demise tells how he hurt his shoulder while throwing a javelin during a ceremonial game and fell into a coma. Assuming he was on his deathbed, the Praetorian Guard announced that Caligula would be Tiberius’ successor, and word quickly spread.

Public DomainThe Death of Tiberius by Jean-Paul Laurens, 1864.

When the emperor suddenly seemed to recover, however, it threw a wrench into the plan to ascend Caligula to the throne. One member of the Guard then made a decisive choice. As panic set in, the soldier went to Tiberius’ chamber and smothered the emperor with his blankets. However, it’s more likely that he simply died from a heart attack.

It’s unclear today if some of the more unsavory rumors about the Roman emperor Tiberius are true. If so, his legacy as a depraved ruler would be well-deserved. Otherwise, perhaps a more nuanced look at his tumultuous life may explain some of the famed leader’s more questionable decisions.

After reading about the complicated legacy of the Roman emperor Tiberius, discover the nine worst emperors in the history of Rome. Then, go inside the fall of Rome.