From Operation Teardrop to the Biscari massacre, these are the atrocities that the U.S. would rather forget.

Wikimedia Commons

One need only say the word “Nuremberg” and most anyone with a passing knowledge of history will immediately recall the few dozen Nazis who stood trial for some of the world’s worst war crimes ever in that German city soon after World War II.

Yet even those with an above-average knowledge of history will scarcely recall the war crimes perpetrated by the Allies, including the United States, during the war.

This is of course because perhaps the greatest spoil of war is that of writing its history. Sure, any war’s victors get to set the terms of the surrender and the peace, but that’s merely the stuff of the present and the near future. The true reward for the winning side is getting to recast the past so as to reshape the future.

So it is that the history books say comparatively little about the war crimes committed by the Allies during World War II. And while these crimes were certainly neither as widespread nor as appalling as those committed by the Nazis, many committed by the United States were utterly devastating indeed:

U.S. War Crimes Of World War 2: Mutilation In The Pacific

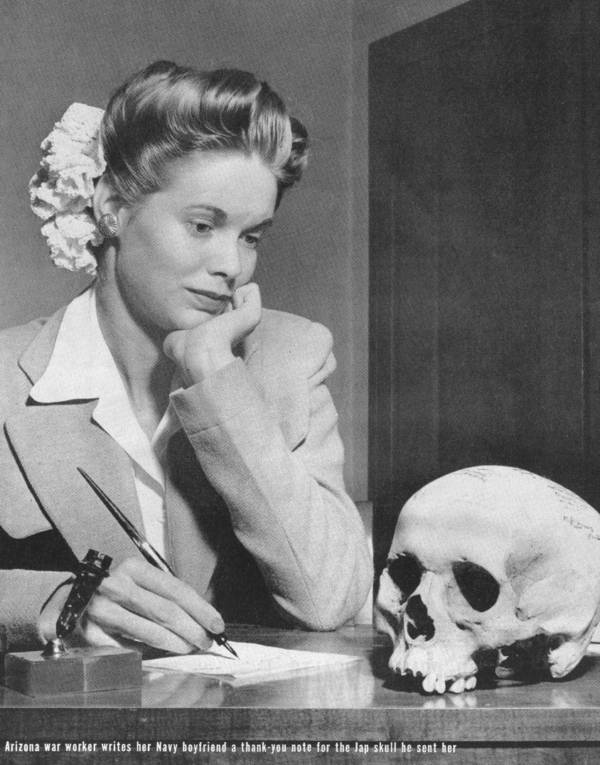

Ralph Crane, Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images via WikimediaPhoto published in the May 22, 1944 issue of LIFE magazine, with the following caption: “When he said goodby two years ago to Natalie Nickerson, 20, a war worker of Phoenix, Arizona, a big, handsome Navy lieutenant promised her a Jap. Last week, Natalie received a human skull, autographed by her lieutenant and 13 friends and inscribed: ‘This is a good Jap-a dead one picked up on the New Guinea beach.’ Natalie, surprised at the gift, named it Tojo. The armed forces disapprove strongly of this sort of thing.”

In 1984, some four decades after the battles of World War II had torn the area apart, the Mariana Islands repatriated the remains of Japanese soldiers killed there during the war back to their homeland. Nearly 60 percent of those corpses were missing their skulls.

Throughout the United States’ campaign in the Pacific theater, American soldiers indeed mutilated Japanese corpses and took trophies — not just skulls, but also teeth, ears, noses, even arms — so often that the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet himself had to issue an official directive against it in September 1942.

And when that didn’t take, the Joint Chiefs of Staff were forced to issue the same order again in January 1944.

Ultimately, however, neither order seemed to make much difference. While it’s understandably all but impossible to determine precisely how many incidents of corpse mutilation and trophy taking occurred, historians generally agree that the problem was widespread.

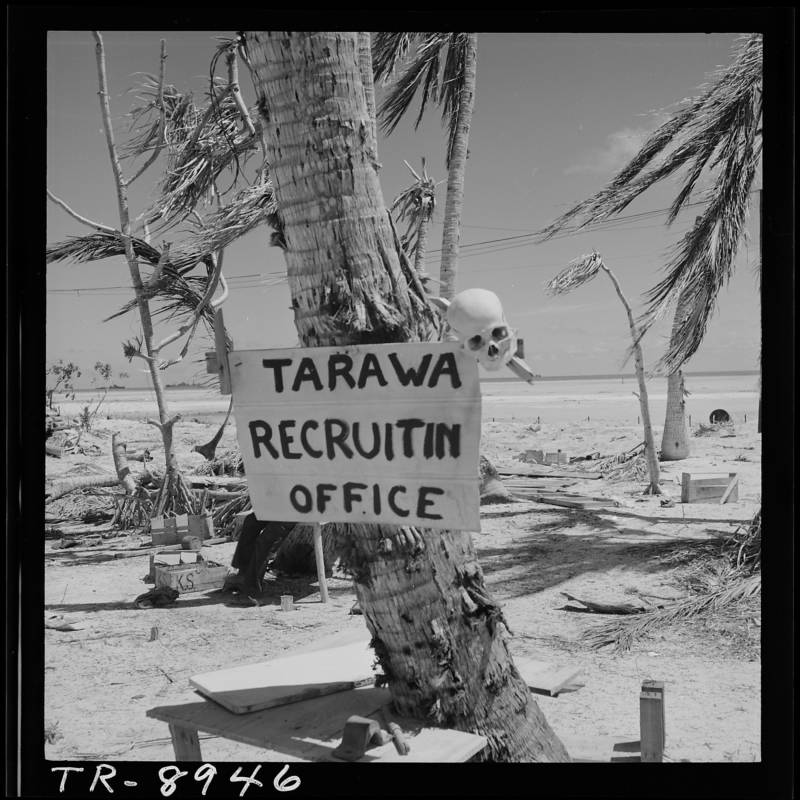

Wikimedia CommonsA skull fixed to a tree in Tarawa, December 1943.

According to James J. Weingartner’s Trophies of War, it is clear that the “practice was not uncommon.” Similarly, Niall Ferguson writes in The War of the World,that “boiling the flesh off enemy [Japanese] skulls to make souvenirs was not an uncommon practice. Ears, bones and teeth were also collected.”

And as Simon Harrison puts it in “Skull trophies of the Pacific War, “The collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered.”

In addition to the assessments of historians, we’re left also with several equally grim anecdotes that suggest the appalling breadth of the problem. Indeed, the extent to which repugnant activities like corpse mutilation were able to sometimes poke their way into the mainstream back home suggests just how often they were going on down in the depths of the battlefield.

Consider, for example, that on June 13, 1944, The Nevada Daily Mail wrote (in a report that has since been cited by Reuters) that Congressman Francis E. Walter presented President Franklin Roosevelt with a letter opener made out of a Japanese soldier’s arm bone. In response, Roosevelt reportedly said, “This is the sort of gift I like to get” and “There’ll be plenty more such gifts.”

Then there was the infamous photo published in LIFE magazine on May 22, 1944, depicting a young woman in Arizona gazing at the Japanese skull sent to her by her boyfriend serving in the Pacific.

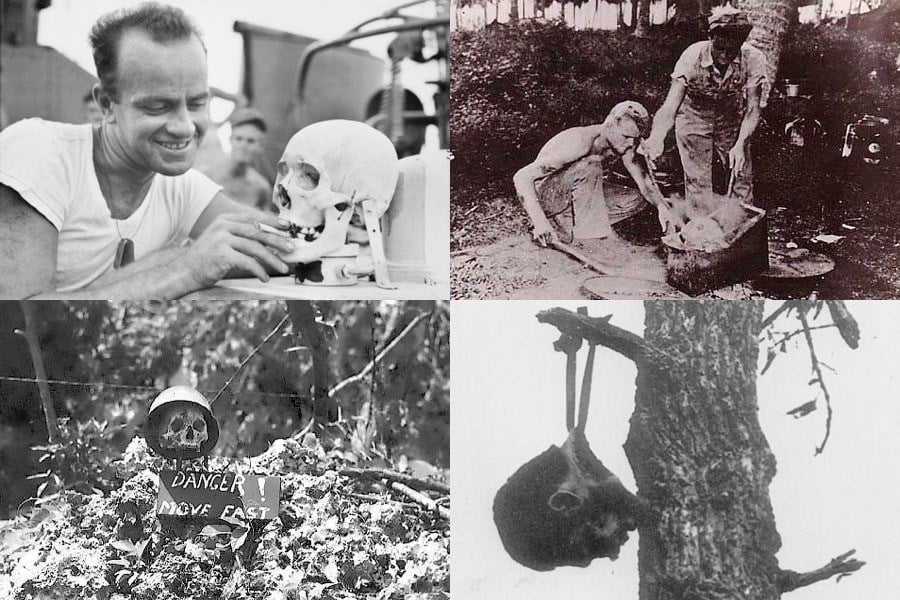

Wikimedia CommonsClockwise from top left: U.S. soldier with the Japanese skull adopted as the “mascot” of Navy Motor Torpedo Boat 341 circa April 1944, U.S. soldiers boiling a Japanese skull for preservation purposes circa 1944, a Japanese soldier’s severed head hangs from a tree in Burma circa 1945, a skull adorns a sign at Peleliu in October 1944.

Or consider that when famed pilot Charles Lindbergh (who wasn’t allowed to enlist but did fly bombing missions as a civilian) passed through customs in Hawaii on his way home from the Pacific, the customs agent asked him if he was carrying any bones. When Lindbergh expressed shock at the question, the agent explained that the smuggling of Japanese bones had become so common that this question was now routine.

Elsewhere in his wartime journals, Lindbergh notes that Marines explained to him that it was common practice to remove ears, noses, and the like from Japanese corpses, and that killing Japanese stragglers for this purpose was “a sort of hobby.”

Surely it’s just this sort of conduct that induced Lindbergh, one of the great American heroes of the pre-war period, to render this damning summation on American atrocities committed against the Japanese in his journals:

As far back as one can go in history, these atrocities have been going on, not only in Germany with its Dachaus and its Buchenwalds and its Camp Doras, but in Russia, in the Pacific, in the riotings and lynchings at home, in the less-publicized uprisings in Central and South America, the cruelties of China, a few years ago in Spain, in pogroms of the past, the burning of witches in New England, tearing people apart on the English racks, burnings at the stake for the benefit of Christ and God. I look down at the pit of ashes….This, I realize, is not a thing confined to any nation or to any people. What the German has done to the Jew in Europe, we are doing to the Jap in the Pacific.