Charles Dickens devoted much of his life to writing about the struggles of the working class. On the eve of his birthday, we look back on the historically awful conditions that may have inspired him to write in the first place.

A portrait of of Charles Dickens at his writing desk in 1858.

Over two centuries ago, Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth, England. Dickens would go on to write an array of now-classics such as Great Expectations, Oliver Twist and A Tale of Two Cities, but Dickens’ life, like that of so many of his characters, did not have an easy beginning.

The prolific English writer entered the labor force at age 12. That experience, brought on by a profligate father who was jailed for his debt, profoundly influenced the subjects and themes of Dickens’ work, which centered largely on the working class and labor conditions.

Instead of moving to jail with the rest of the family as was common at the time, Charles was put to work at a boot-blacking factory for around ten hours a day. Dickens would eventually translate his experiences there into the books that would one day make him rich and famous, particularly Oliver Twist.

In spite of his fame, Dickens never lost his connection to the British working class, and fiery critiques of Victorian society are a constant throughout his works. This wasn’t just for the sake of a provocative novel: as the historical record shows, there was a lot to shout about at the time. Let’s look at five of the most shocking labor practices of the Dickensian age.

Child Labor: The Mills and the Chimneys

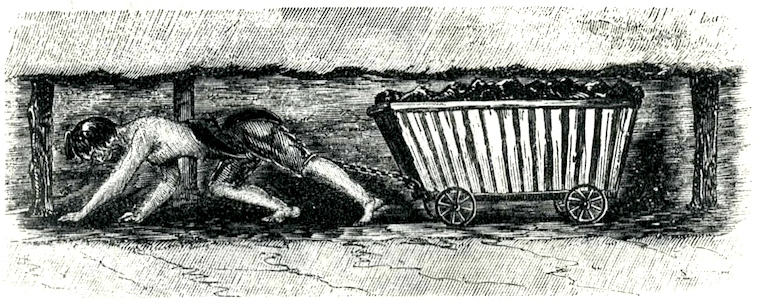

A young girl drags a load of coal through a mine shaft in 1800s England.

Although the late 18th century Industrial Revolution did not create child labor, it did allow for its wide use throughout Britain. Kids could often be found working in factories and mines, and dropping out of school in order to do so was by no means a problem.

Regulations at these factories and mines were few and far between: the Cotton Mills and Factories Act of 1819 put the minimum working age at 9 years old. The law also stipulated that children between 9 and 16 years old could work a maximum of 12 hours per day.

In 1832, the Ten Hour Bill passed. As its name implies, the law limited working time to a “generous” 10 hours a day. In 1834’s Chimney Sweeps Act, Parliament pushed the legal age for cleaning chimneys up to 14 years old.

Dickens himself saw what horrible consequences child labor could have on childhood. In A Christmas Carol, Dickens describes children Ignorance and Want as follows:

“Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility.

Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds.” In Bleak House, Dickens’ humor is almost too painfully wry when he writes, “It is said that the children of the very poor are not brought up, but dragged up.”

House work: Masters and Maids

Thomas Kennington’s famous painting, “A Pinch of Poverty,” captures the distress of the poor in Victorian England.

The Master and Servant Act of 1823 criminalized any employee who breached a contract. Indeed, an indentured servant who attempted to cut his or her ties with a master and seek work elsewhere could be considered a “criminal,” while their often-abusive masters remained shrouded in legal protection. This act — meant to discourage workers from organizing and demanding better treatment — effectively forced employees to stay loyal to their masters irrespective of what they did, out of fear of prison.

And this fear was real: In a single year, decades after the law was passed, over 10,000 servants were tried for violating this law. None of their masters faced prosecution.

Wrote lawyer Ernest Jones at the time, “[I]n one year alone, 1864, the last return given, under the Master and Servants Act, 10,246 working men were imprisoned at the suit of their masters — not one master at the suit of the men!”

Debt prisons: pay for your stay while you pay down your debt

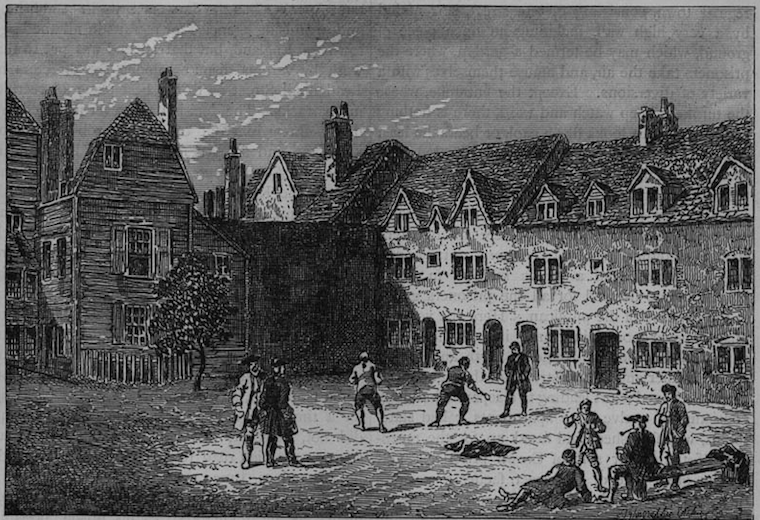

Marshalsea Prison around the time Dickens’s father would have been an inmate.

We can’t forget debt prisons, whose existence and use personally affected Dickens and may have triggered him to focus on themes of social inequity in his work. Debt put his own father and family in jail: In 1824 John Dickens, along with his wife and kids, was sent to South London’s Manshalea prison, whose fictionalization Dickens describes in Little Dorrit:

“The imprisoned air, the imprisoned light, the imprisoned damps, the imprisoned men, were all deteriorated by confinement. As the captive men were faded and haggard, so the iron was rusty, the stone was slimy, the wood was rotten, the air was faint, the light was dim. Like a well, like a vault, like a tomb, the prison had no knowledge of the brightness outside.”

Only debtors stayed in Marshalea. They had to pay rent in jail as well, which had the effect of compounding debt and thus keeping debtors in jail for years. When Dickens’ father was sent to Marshalea, he owed £40 — which when converted to present day USD is approximately $4,700, assuming inflation of 2 percent.

Hard times: hangings and forced extradition to Australia

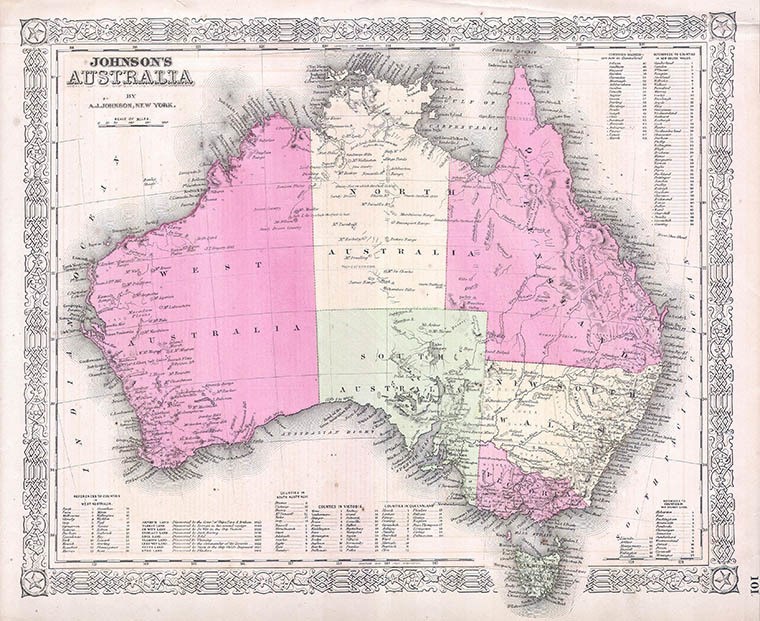

An 1865 map of Australia. Image Source: Wikipedia

Many types of punishment had been outlawed by the time Queen Victoria was crowned, but hanging, corporal discipline such as whipping, hard labor, and forced military service were all still common punishments for less than heinous crimes — as was forced extradition to Australian prisons. Death sentences were doled out for an array of crimes, which spanned from serious offenses such as murder to minor illegal acts like stealing food or picking pockets.

Given what awaited the convicted in prison, though, death might have been the better option. In prison, inmates were assigned tortuous, meaningless tasks, one example being the crank, a mechanism with a handle that inmates had to turn non-stop, even though the cranking didn’t actually do anything.

Whereas some inmates were at least building roads or working on the docks, prisoners punished with operating the crank had to turn the handle thousands of times a day as determined by their guards. The goal was clear: Mental domination and destruction.

The Workhouse

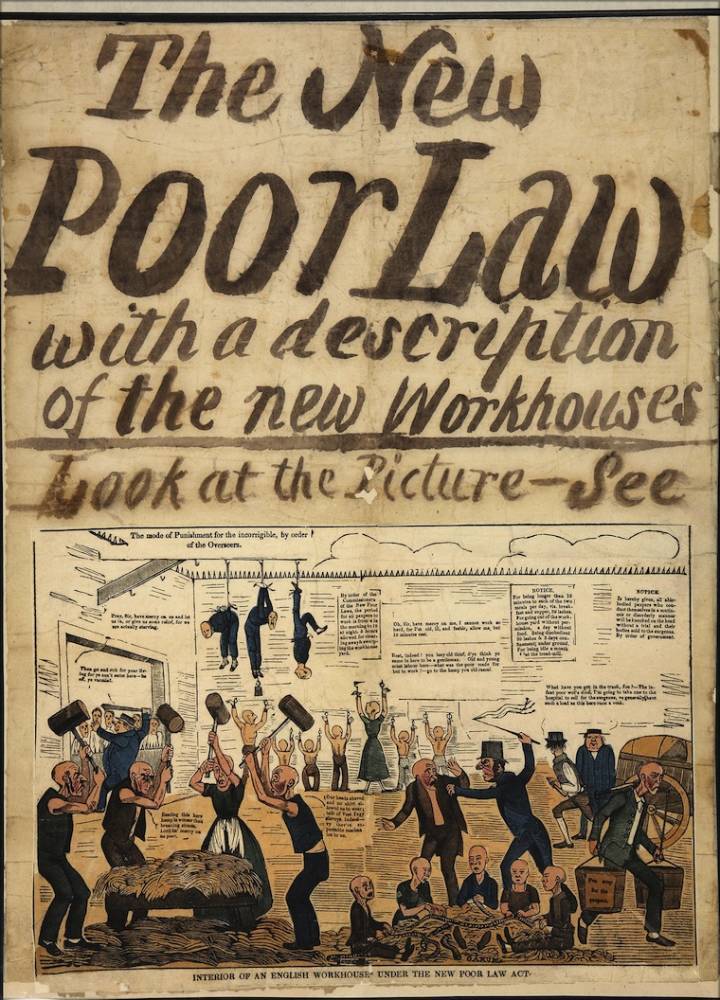

A contemporary portrayal of the horrid conditions in a Victorian poor house. Source: The British Library

When Dickens was in his early twenties, the English governing class passed the Poor Law Act Amendment, or the New Poor Law. Over the next twenty years, this law made it such that over 500 new “workhouses” or “poorhouses” went up in jolly ol’ England.

These homes weren’t a governmental effort to provide the poor or homeless with shelter; rather, the government thought that such establishments would save them money.

First, the workhouses were intentionally made to be so nasty that only the most desperate would subject themselves to living there. The government also cut spending on food and any semblance of comfort while simultaneously forcing tenants to work for their place in the prison-like residences.

As one fictional humanitarian tells Ebenezer Scrooge in Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, many Englishmen would rather die than end up in a workhouse.

Scrooge, of course, replies, “If they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population.” Perhaps one of the author’s most famous characters, Oliver Twist, starts his journey “farmed” out to one of these devastating locales.