Vivien Thomas did groundbreaking work in the field of cardiac medicine. Incredibly, he had no medical degree.

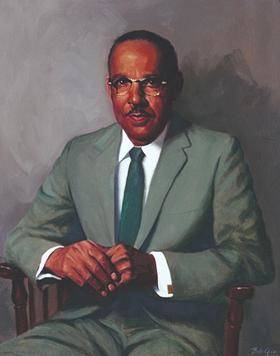

Wikimedia CommonsA portrait of Vivien Thomas.

In a time when over 2,000 people undergo heart transplants each year in the United States and go on to live normal lives, it is hard to believe it wasn’t that long ago when cardiac medicine was a relatively new field. Moreover, the story of two of the field’s pioneers is perhaps more remarkable than any surgery they performed.

Vivien Thomas was son to a carpenter and grandson to a slave. He was born in Louisiana in 1910 and moved to Nashville as a child at a time when Jim Crow segregated blacks and whites. Yet he did not let the era’s institutional racism deter him from his dream of attending Tennessee State College and then going on to medical school.

However, the Great Depression came and hit people regardless of color, class, or aspirations. All of the savings Thomas had built up from carpentry were wiped out. The young man did not give up hope just yet and applied for a laboratory assistant position at Vanderbilt University.

Vivien Thomas And Alfred Blalock

He got the job. At first glance, the doctor for whom Thomas would be working seemed to embody the spirit of the Confederacy.

Alfred Blalock was born in Georgia and a distant cousin of Jefferson Davis. He had been in a fraternity at the University of Georgia before going on to study surgery at Johns Hopkins University. Despite all of this, Blalock was less interested in his potential assistant’s skin color than his capacity to learn, stating he was looking for “someone in the lab whom I can teach to do anything I can do, and maybe do things I can’t do.”

Vivien Thomas turned out to be the perfect foil to Blalock.

He was able to translate the surgeon’s outlandish-seeming ideas into reality through detailed experiments. It wasn’t long before the lab assistant (who lacked even just a college degree) was performing operations in the laboratory himself. He poured through medical textbooks all day and stay up well into the night with Blalock performing experiments. The laws that separated blacks and whites in the outside world did not exist inside the lab, and the two men worked as partners.

Thomas noted “neither one of us ever hesitated to tell the other, in a straightforward, man-to-man manner, what he thought or how he felt.”

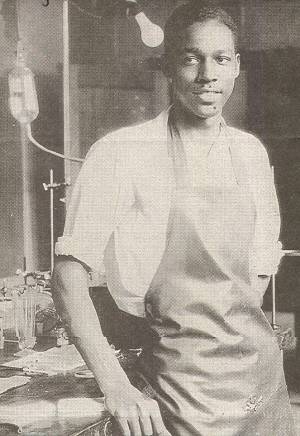

Wikimedia CommonsThomas at work in the lab.

In Blalock, Thomas had a friend who was willing to stand up for him. Thomas’ brother had previously sued the Nashville Board of Education for paying him a lower salary as a teacher because of his race. Although he won his lawsuit, he lost his job. When Thomas found out that after four years in the lab at Vanderbilt, he was still designated and compensated the same as a janitor despite doing the work of a senior research fellow, he went to Blalock. A few weeks later, Thomas and a fellow black coworker saw their paychecks increase.

Thomas had to deal with salary issues for years, but Blalock consistently advocated for him. When Thomas was nearly forced to move back to Tennessee after his groundbreaking surgery because the salary he was paid at Johns Hopkins Hospital was so low, Blalock personally negotiated a new offer that meant his partner could not only stay, but would never have to worry about money again.

In 1937, Blalock was offered a position as chairman at a Detroit hospital, which would have offered him a tremendous opportunity to conduct his own research. However, the hospital staunchly refused to hired blacks. Blalock declined the offer, stating that he and Thomas were “a package deal.” When Johns Hopkins offered Blalock a position as surgeon-in-chief a few years later – while allowing Thomas to join him – Blalock accepted.

The day Vivien Thomas first walked over to his new office in the hospital wearing his lab coat, he literally stopped traffic. As Thomas well knew, the only black men employed by hospitals at the time were janitors, but he and Blalock continued their collaboration relatively free from concern. Then, in 1944, they got the chance to show the world what they could do together.

Wikimedia CommonsAlfred Blalock, although a white southerner, supported Thomas throughout his career.

Treating Blue Baby Syndrome

“Blue babies” are infants suffering from a heart defect that prevents blood from reaching their lungs. The resulting lack of oxygen causes the infants’ extremities to turn blue. Eileen Saxon, one of the many blue babies born in the United States, was just 15 months old when her parents brought her to Johns Hopkins to see what could be done to help her.

Wikimedia CommonsJohns Hopkins Hospital where Blalock and Thomas worked.

Before Baby Eileen, no doctor had even attempted to operate on the heart, so Blalock shocked everyone when he declared he was going to do just that. He would be the first doctor to attempt repairing a human heart; at the time the surgery was believed not only impossible, but almost taboo. As Thomas put it,

“Nobody had fooled around with the heart before, so we had no idea what trouble we might get into. I asked the Professor whether we couldn’t find an easier problem to work on. He told me, ‘Vivien, all the easy things have been done.’”

He and Thomas were the only team in the world capable of performing the surgery and at the end of a harrowing four and a half hours, Eileen was a healthy pink. During the historic operation, Blalock insisted that Thomas be right behind him. Two men who would not have been allowed to sit side-by-side on a bus worked together on a groundbreaking procedure in the history of medicine.

Many Lives Saved

At the time of Blalock’s retirement in 1964, more than 2,000 children had undergone the life-saving procedure at Hopkins. Thomas continued to work at Hopkins for another 15 years as director of the Surgical Research Laboratories.

Although he never did formally earn his medical degree, in 1976 Johns Hopkins University awarded him an honorary doctorate. Vivien Thomas died in 1985 at the age of 75, just a few days before the publication of his autobiography Partners of the Heart.

Enjoy this article about Vivien Thomas? Next, read about Robert Liston – the reckless surgeon who managed to kill his patient and also two bystanders. Then see these powerful images of the Civil Rights movement.