Between 1931 and 1962, some 2 million prisoners passed through the Arctic gulags at Vorkuta — and 200,000 of them perished from starvation, overwork, and temperatures as low as -40 degrees Fahrenheit.

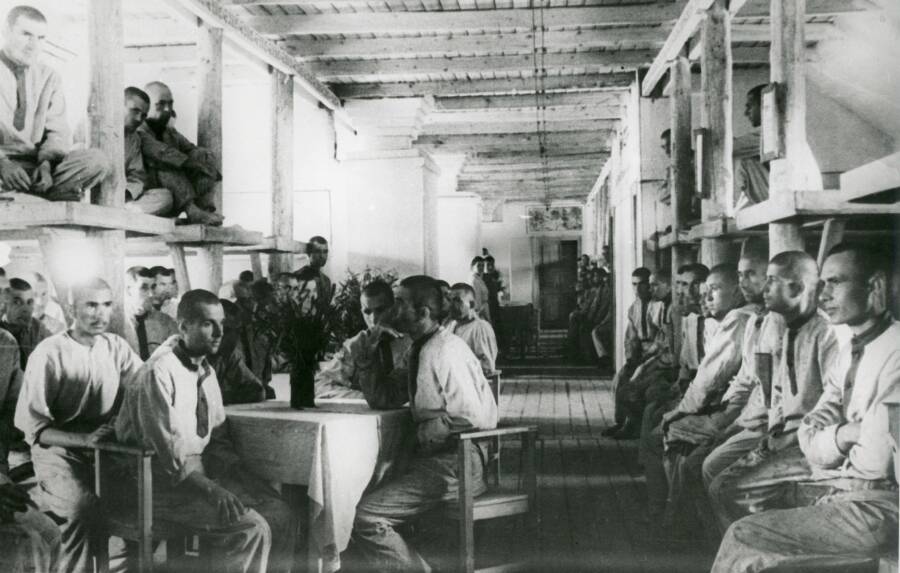

Laski Diffusion/Getty ImagesPrisoners of Vorkutlag, or the Vorkuta Gulag, in 1945.

From the 1920s until the 1950s, millions of people passed through Soviet gulags, remote labor camps where political prisoners, common criminals, and rebellious peasants were forced to work. But few were as infamous as the gulags at Vorkuta.

There, about 100 miles north of the Arctic circle and over 1,000 miles from Moscow, millions of prisoners toiled in the region’s coal mines. Spread across some 130 camps, the prisoners of the so-called Vorkutlag suffered from long workdays, frigid cold, and a lack of basic supplies.

The two million people who passed through the Vorkutlag over the 20 years of its operation were criminals, intellectuals, Nazis, and others caught up in Stalin’s Great Purge to eliminate political threats. Some 200,000 of them perished there. Others rose up against their guards. And many of them, even once the camps closed down, remained in Vorkuta.

The Beginning Of The Vorkuta Gulag

According to Time, Russian leaders had eyed the isolated stretch of land in present-day Vorkuta as a good place for political prisoners as far back as the 1840s under Czar Nicholas I, who ultimately decided that the frigid landscape was “too much to demand of any man that he should live there.”

But the later Soviet bureaucrats disagreed. For them, the gulag system served two purposes. One, it provided a convenient place to imprison anyone — from “class enemies” to rebellious peasants — who resisted Soviet policies. Two, the gulags provided Soviet administrators with free labor with which they could industrialize the country.

And so when coal was discovered in the Komi Republic in 1930, it set the stage for the birth of a new set of forced labor camps. According to New/Lines Magazine, a small group of about two dozen prisoners, geologists, and guards made their way to the area in 1931, where they dug one of Vorkuta’s first mines the next year.

“The heart compressed at the sight of the wild, empty landscape,” one of the prisoners, a geographer named Kulevsky recalled, according to Anne Applebaum’s Gulag: A History. “The absurdly large, black, solitary watchtower, the two poor huts, the taiga, and the mud.”

From that point, this isolated coal mine 1,200 miles north of Moscow expanded rapidly into one of the Soviet Union’s largest gulags.

New/Line Magazine reported that by 1938, it had 15,000 prisoners. By 1946, Vorkutlag and a neighboring camp held over 60,000 prisoners.

Torture In The USSR’s Most Notorious Camp

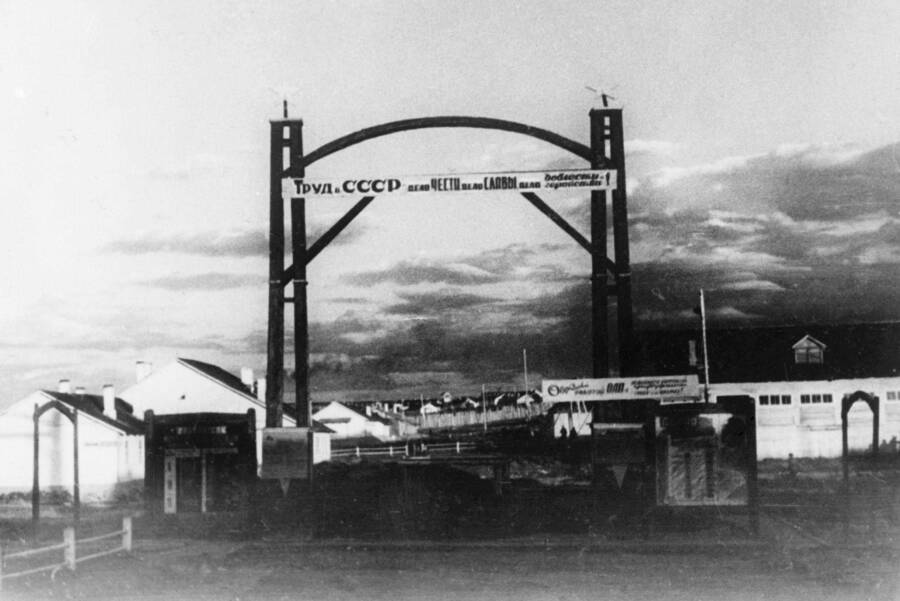

Laski Diffusion/Getty ImagesThe gate of this Vorkuta coal mine reads, “Working in the USSR will make you a hero.”

Life at Vorkutlag was brutal — if you even survived the journey there.

According to New/Lines Magazine, prisoners were brought to the camp by packed trains where guards referred to them as “white coal” and dropped off corpses at every stop. Upon arrival, the prisoners would be greeted with signs like “Work in the USSR Is a Matter of Honor and Glory” and “With an Iron Fist, We Will Lead Humanity to Happiness.”

At first, the arrival of prisoners outpaced the construction of the camp. According to Russia Beyond, Vorkutlag’s earliest inmates had to live in tents.

But the barracks, once they were built, weren’t much of an improvement. Time reported that prisoners lived in camps surrounding a mine, where they slept in bunk beds, used a bucket as a toilet, and plastered cracks in the walls with mud in the futile hope of keeping out the cold.

Indeed, the cold was one of the defining features of life in Vorkuta, where temperatures could plunge to 40 degrees below zero, winters lasted up to 10 months, and violent snowstorms made life treacherous.

“The watchdogs of our guards sensed the approach of a snowstorm before we did,” one prisoner, a general in the Spanish Civil War, recalled according to Time. “They began to howl and whine, and this would be the signal to start cutting holes into the frozen ground where there was no other shelter.”

According to the general, one group of 150 prisoners got caught during a snowstorm just feet from a mine and were promptly abandoned by their guards. “The next shift going to the mine passed small white mounds,” he recalled. “Nobody troubled to dig the bodies out. But one of the officers in the camp command said: ‘It is a pity we’ve lost their clothing.'”

Despite the cold — and despite the fact that most prisoners lacked basic supplies like underclothes or warm boots — they were expected to get up at around 5 a.m. and work 12-hour days. And those who tried to escape from the inhumane conditions at the Vorkuta gulag were often brutally beaten, stripped naked, and thrown into unheated solitary confinement.

By 1953, many of the prisoners had had enough. That year, Joseph Stalin died — and the prisoners at the Vorkutlag refused to work. Time reported that one prisoner even declared, “I am sick of just working, working until I drop dead in the pit or the tundra sucks me up.”

That July, they went on strike. But their resistance was short-lived. On August 1, troops fired on the strikers, killing dozens and injuring scores more.

However, the so-called Vorkuta Uprising turned out to be the camp’s dying gasp. The era of the gulag was ending, and the Vorkutlag shut down in 1962. By then, some 200,000 had perished while imprisoned there.

The Haunting Legacy Of Vorkuta Today

Maria Passer/Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesVorkuta is something of a ghost town in 2021, with its population dwindling.

Following the closure of the Vorkutlag, many of its prisoners left the region. But some — having nowhere else to go — stayed. And some Soviet citizens even opted to move to the site of the former gulag.

According to Radio Free Europe, the exodus of gulag prisoners left Soviet authorities with serious a problem. Though the inmates had left, the mines still needed to be worked. So authorities offered potential miners high salaries and plenty of perks to move to the isolated, frigid region.

As a result, Vorkuta blossomed into a thriving city with schools, stores, and apartment blocks. Fueled by the 13 mines which encircled it, its population grew to 250,000 by the late 1980s.

But Vorkuta’s prosperity didn’t last. Today, only four of its 13 mines remain, its suburbs have become ghost towns, and its overall population has plummeted to around 60,000. Though rent is cheap, residents must grapple with the cold and the city’s isolation from the rest of Russia.

“What we see now, 30 years after the Soviet collapse, is the drawn-out death of Vorkuta,” Alan Barenberg, a historian at Texas Tech University and the author ofGulag Town, Company Town: Forced Labor And Its Legacy In Vorkuta, told Radio Free Europe.

“It’s no longer an ideological imperative to prove to the world that maintaining a coal-mining city of 250,000 people in the Arctic is a triumph of Soviet ingenuity — so you see the widespread abandonment of settlements and mines, with more surely to come.”

Though Vorkuta’s future is uncertain, its past is all too clear. Here, in a city of endless winters and frigid temperatures, hundreds of thousands died brutal deaths. Whatever happens to the city of Vorkuta next, its legacy will remain inextricably tied to the suffering at the Vorkutlag.

After reading about the Vorkuta gulags, witness the fall of the Soviet Union. Or, go inside the debate over how many people Joseph Stalin killed.