The Black Death was the deadliest pandemic in human history and scholars still struggle to map when and where it began. But some of the most compelling theories are truly disturbing.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel from 1562 depicts the horrific consequences wrought by the Black Plague.

By the end of its first decade, the Black Plague had decimated over 60 percent of Europe’s population. It would return in waves every 10 to 20 years before it finally subsided in the mid-18th century.

But when and where did the Black Plague start, exactly? And where in Europe did it first appear?

Some scholars believe that the plague was first brought to Europe in an act of biological warfare when the Mongols catapulted disease-ridden corpses into the city of Kaffa beginning in the early 1340s. Others wonder whether the plague had already existed among Europeans for centuries.

Let’s take a closer look at all the forces that could have led to the start of the Black Plague.

The First Historical Accounts Of The Black Plague

Wikimedia CommonsThe Black Death as it affected Florence in 1348, according to Boccaccio’s The Decameron.

Early researchers still do not know for certain where and when the Black Plague first arrived in the historical or genetic record. The disease itself is caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis and it had already long existed on the fleas of wild rodents. So when early civilizations encroached on the habitats of these flea-ridden rodents, the bacterium naturally jumped to humans.

According to a 2010 study published in Nature, DNA showed that the plague evolved in China over 2,000 years ago and was later brought to Europe via the Silk Road. This theory has prevailed among Western researchers.

On the other hand, however, there is also DNA evidence to suggest that the plague hit Europe as early as 5,000 years ago.

Interestingly enough, other scholars believe that the first written account of the plague actually appeared in the Bible.

The story of the Ark of the Covenant tells of a conflict between the Philistines and Israelites that supposedly took place in the 12th century B.C. and ended when the Philistines confiscated an ark from the Israelites. When that ark was then paraded around Philistinian cities, residents were said to be ravaged by an inexplicable illness.

One passage in the Septuagint, or the Greek Old Testament, reads:

“And the hand of the Lord was heavy upon Azotus [Ashdod], and he brought evil upon them, and it burst upon them in the ships, and mice sprang up in the midst of their country, and there was great and indiscriminate mortality in the city.”

The plague is also mentioned in several instances of the Hippocratic corpus, a medical journal from ancient Greece. However, it is difficult to determine which records of plague refer to the specific disease that caused the Black Death in particular or actually refer to other illnesses.

With that in mind, a specific record of bubonic plague does not appear for certain in historical medical records of any ancient civilization until at least a thousand years later. This account chronicles the plague as it swept through the Crimean region following a historic seige by the Mongols on the city of Kaffa in 1343.

Did A Mongol Seige Bring The Black Death To Europe?

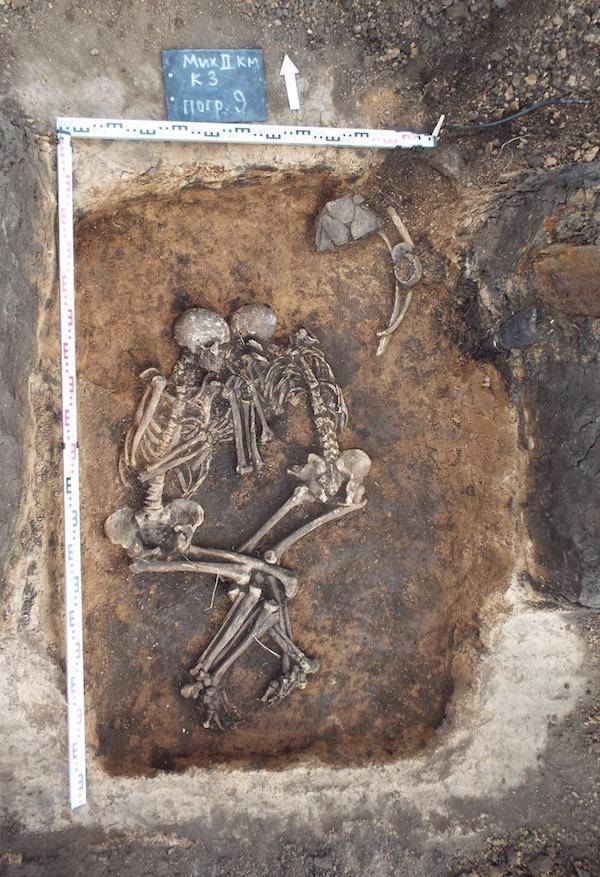

V.V. Kondrashin & V.A. Tsybin/SpyrouThe remains of two plague victims are uncovered in Mikhaylovka, Russia.

Historians commonly cite the memoir of Gabriele de’Mussi (or de Mussis) to explain how the Black Plague arrived in Europe. According to de Mussi’s account, the plague arrived in 14th-century Europe following a Mongol attack on Kaffa.

De’Mussi was an Italian notary who wrote a vivid, secondhand account of the siege of Kaffa — which is now Feodosiya in Ukraine — that offered a startling insight into the spread of the plague across Europe.

Before the siege, Kaffa was a thriving hub of commerce with a diverse population of roughly 16,000 residents made up of Genoese, Mongols, Armenians, Jews, and Greeks.

Genoese merchants relied heavily on the trade connection between Kaffa and Tana (now Azov of Russia) along the Don River. But despite a peace-keeping agreement between the Genoese and the Mongols, the two nations struggled for ownership of the city.

Wikimedia CommonsTheodosia Castle where the city of Kaffa once stood.

The city was officially attacked by the Tartar-Mongols in 1343. They lay siege to the city repeatedly until in 1346 when a mysterious illness befell the Tartar-Mongols, killing thousands of their soldiers daily.

According to de’Mussi, the Mongols decided to use their plague-ridden corpses as weapons, catapulting them over the city’s walls:

“What seemed like mountains of dead were thrown into the city, and the Christians could not hide or flee or escape from them, although they dumped as many of the bodies as they could in the sea. And soon the rotting corpses tainted the air and poisoned the water supply, and the stench was so overwhelming that hardly one in several thousand was in a position to flee the remains of the Tartar army.”

De’ Mussi paints a visceral scene of biological warfare in the Middle Ages. It wouldn’t be the last time such methods were used to disarm and occupy a country. During World War II, the Japanese established a military outfit called Unit 731 which tested bioweapons on Chinese citizens. That same unit nearly waged biological warfare upon Southern Californians in the United States during the final months of World War II in an operation called Cherry Blossoms At Night.

However, it is unlikely that the Tartar-Mongols knowingly infected the city of Kaffa because an understanding of bacteria did not yet exist. Instead, people of the Middle Ages believed in the now-debunked theory of miasmas, which asserted that disease was caused by foul odors.

One professor at the University of California, Davis, on the other hand, posits that the Mongols indeed had a good enough understanding of disease to have intentionally spread it. He does concede that “the siege of Kaffa, for all of its dramatic appeal, probably had no more than anecdotal importance in the spread of plague, a macabre incident in terrifying times.”

But for those who do believe that the Mongol attack played a significant role in infecting Europe, the thought is that after the Italian and other international merchants fled the city following the siege, they brought plague-ridden rodents back home with them on their ships thus spreading the plague throughout the continent.

Other Theories On How The Black Plague Started In Europe

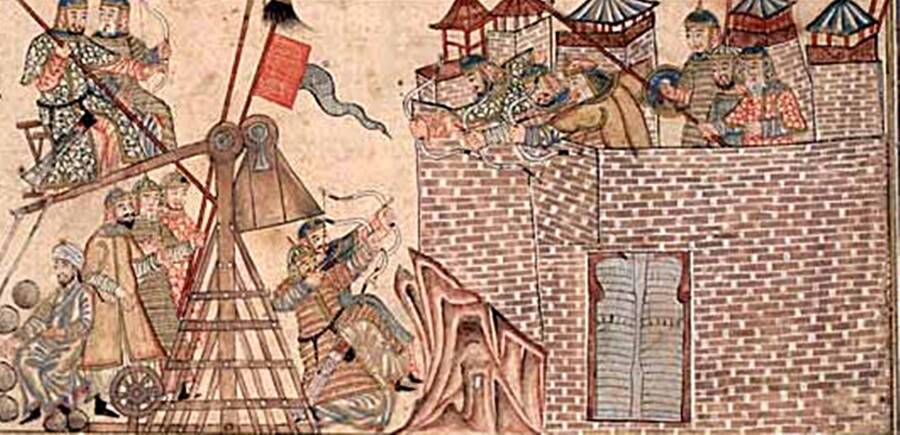

Wikimedia CommonsThe Mongol siege of Kaffa may have looked something like this, though this is actually a depiction of an entirely different Mongol siege.

Plague historian Ole J. Benedictow, author of The Black Death 1346-1353: The Complete History, has painstakingly tried to identify where the plague likely first appeared among humans and to then map out how it spread through Europe.

In his book, Benedictow proffers that the plague probably originated in an area that stretches from the northwestern shores of the Caspian Sea to Southern Russia. Indeed, according to the CDC “historians generally agree that the outbreak moved west out of the steppes north of the Black and Caspian Seas” and then spread through Europe and the Middle East.

Benedictow explains that Constantinople in modern-day Turkey was actually one of the first major cities to be severely hit by the plague in 1347. From there, he maps the Black Death to have traveled to the islands of Aegean, Trebizond in Asia Minor, and beyond.

The Black Plague then made its way westward over the Silk Road where it eventually decimated Europe. The constant commerce between the Mongols and the Mamluk Empire in Egypt possibly contributed to the Black Death’s reach all the way to Alexandria by the autumn of 1347, just two months after the outbreak in Constantinople.

According to Arab chronicler Al-Maqrzi, there was a large ship of more than 300 merchants, slaves, and crew that sailed out of Alexandria’s bustling port toward Constantinople. Upon its return, there were only 40 people left aboard.

The ship either carried the disease with them to Constantinople or contracted it there. Either way, the passengers were likely vectors of the plague — and the remaining survivors later died while still docked.

The Spread Of The Plague Was Likely The Result Of Many Factors

Wikimedia CommonsJanibeg, the Mongol warrior who commanded the siege of Kaffa.

According to a 2002 paper by microbiologist Mark Wheelis, even though the siege of Kaffa can be considered a significant record of the early spread of the Black Plague, it can not be considered the defining event that introduced the disease to all of Europe.

Wheelis argues that the Black Plague showed up in Europe beginning in July 1347, a year after the siege of Kaffa, but if the plague was spread after being brought back by merchants fleeing the city, then it would have appeared much earlier in the historical record. After all, the Mongols first attacked in 1343 and the Italians arrived back in Europe in the spring of 1347.

Furthermore, de’ Mussi’s account has yet to be corroborated by a separate, secondary source. It is also plausible that there were racial motivations behind de’Mussi’s account, seeing as he blamed the so-called “heathen Tartar races.”

Wikimedia CommonsMap of the spread of the Black Plague.

A single instance, like an act of war, can not be considered the defining moment that the plague was introduced to Europe. Instead, it was likely a combination of factors like transatlantic trade and yes, war, working simultaneously, and over great distances that contributed to its deadly reach.

Next, read about the discovery of two Black Death victims holding hands in a shared grave. Then, discover the terrifying ordeal of being a plague doctor in Medieval times.