Archeologists analyzed a cache of fossilized poop in the Conejo Rock Shelter and found remains of an entire venomous snake, including a head, a fang, and scales.

Wikimedia CommonsArcheologists found the remains of a whole diamondback rattlesnake or copperhead inside ancient fecal matter.

Sometimes remarkable discoveries can be found in unexpected places. That’s what happened when archeologists examined fossilized human poop and found the remains of an entire snake, including an intact fang.

It’s an unusual discovery that researchers believe indicate the existence of ritualistic traditions among hunter-gatherer populations that began living in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of southwest Texas starting more than 12,000 years ago.

The human-produced coprolite—or dried poop—containing the snake’s remains came from a vast archeological collection of 1,000 samples that were gathered by researchers in the late 1960s.

The Conejo Rock Shelter in California, where the excavations for the coprolites largely took place, is believed to have served as the basecamp for indigenous hunter-gatherers. The large amount of fecal matter found in one part of the shelter suggests that the space was used as a latrine.

The bizarre discovery was made during a recent examination of the coprolites by archaeologist Elanor Sonderman, a researcher at Texas A&M University, and her team.

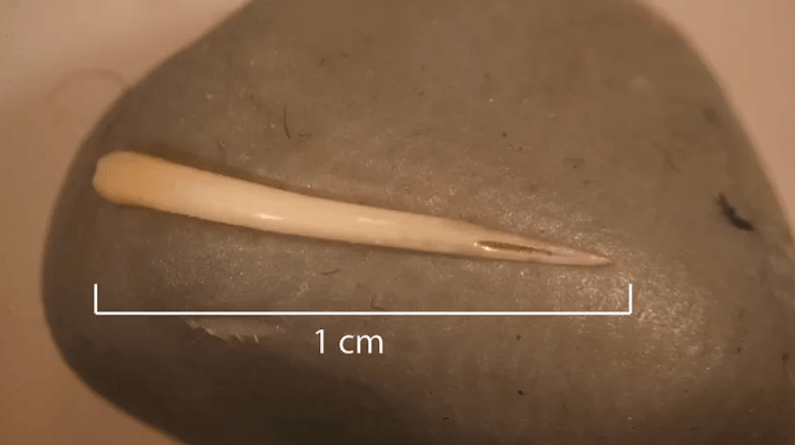

As Sonderman’s team was going through the samples of dried poop, they came across one in particular which contained the scales, bones, fang, and head of a snake. Based on the size of the well-preserved snake fang, which measured one centimeter long, the snake that was eaten was likely either a diamondback rattlesnake or copperhead. Copperheads are commonly found across North America, and though their venom is relatively mild, they have a fairly aggressive temperament.

But could it be possible that these snake remains were just part of natural debris that somehow got stuck on the fossilized poop? Sonderman said that it is unlikely.

“Based on the archaeological context it is possible that large portions of plant materials might have adhered to the coprolite soon after deposition but these exterior materials were removed from the coprolite before analysis,” Sonderman told Gizmodo. “The fang was inside the coprolite. Not hanging around on it.”

However, finding wholly-consumed animals inside old fecal matter is not particularly unusual for researchers, nor is the consumption of snakes by humans of times past.

According to the researchers, the pre-Columbian hunter-gatherers in the Lower Pecos region had a largely carnivorous diet, though they foraged what they could in the harsh desert landscapes. Researchers have found evidence of rodents, fish, reptiles, and other desert-dwelling animals in coprolite samples before. These humans also ate a considerable amount of vegetation for nutritional and medicinal purposes.

E. M. Sonderman et al., 2019Fossilized poop with fang.

Interestingly, the culture of the Lower Pecos peoples is well-known for their elaborate rock art that frequently featured drawings of snakes. Some indigenous cultures are known to eat snakes as part of their diet.

For example, the Tepehuan people of Northeastern Mexico ate rattlesnakes, while the Ute people of modern-day Utah and Colorado also ate these reptiles. But the snakes are consumed only after removing inedible parts like the rattle and skin, and cooked above a fire.

By comparison, the snakes remains that were found in the fossilized feces are highly unusual. The body parts that were found in the coprolite suggest that the snake was eaten whole and raw. The researchers believe it to be the first evidence of whole-snake consumption in the fossil record.

As the researchers point out in their new study that was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, the snake was likely consumed for ceremonial or ritualistic reasons, not as a nutritional supplement.

In order to come to this conclusion, researchers looked at what else they found in the ancient droppings. For one, other materials found in the same sample of human poop show a bevy of vegetation, including Agave lechuguilla and Liliaceae flowers, Dasylirion fibers, and Opuntia, all of which were plants typically consumed by the Lower Pecos peoples.

They also found remains of rodents, which were also regularly eaten. Combined, these materials point to a relatively normal diet, suggesting that the individual was not desperate for food.

The research paper stated that snakes were “considered to hold power to act upon certain elements of the earth,” and because “of their power and role in various mythologies, many cultures around the world include snakes as a feature of ceremonies and rituals.”

While looking through piles of old fecal matter may sound gross, the discoveries within these ancient droppings can give scientists clues to societies of ancient times.

Next, read about San Francisco’s “poop patrol”, a special unit tasked with cleaning up the city’s growing public feces problem. After that, learn about the weird life of poop-eating and self-mutilating rocker, GG Allin.