Wilfred Owen was a WWI soldier, whose realistic depiction of life in the trenches gave rise to a new kind of war poet.

Wikimedia CommonsWilfred Owen. 1920.

Before the peace protest songs of the 1960s and black comedy war satires like M*A*S*H in the 1970s, there was Wilfred Owen. The World War I soldier and poet used his distressing experiences in combat to write poetry on the horrors of warfare. His work was alternative and substantial in that it went against both the general public’s feelings about war, as well as the patriotic style of poetry that was popular among previous war poets.

Owen wrote almost all his poems in the span of a single year, though only five of them were published during his lifetime. Killed in action exactly one week before the armistice that ended the war, Owen wouldn’t live to see his poetry released in anthologies and collections that are still read today.

Wilfred Owen Grows Up And Enlists

Wilfred Owen was born in Shropshire, England on March 18, 1893. The oldest of four children, he was born in his grandfather’s spacious house where the family lived for several years. His father was a former seaman who spent time in India, and after returning to England to marry Owen’s mother, he felt constrained by his dull railway station job. Owen developed a close relationship with his mother, Susan, whose intellectual and musical goals were limited by her marriage.

After his grandfather died in 1897, Owen and his family moved around England several times. In 1911, he graduated from the Shrewsbury Technical School, after which he decided to volunteer as a Reverend’s assistant in the Church of England in Oxfordshire to figure out if he wanted to commit to becoming a clergyman.

His responsibilities included caring for the parish’s sick and poor members, which broadened his perspective on larger social and economic issues. But as a result, he became disenchanted by the Church and its lack of response to those who suffered.

Wilfred Owen had taken an interest in the Great War and in 1915 he enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles regiment of the British Army Reserve. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant. On Dec. 29, 1916 he was deployed to France.

Documenting His War Experiences

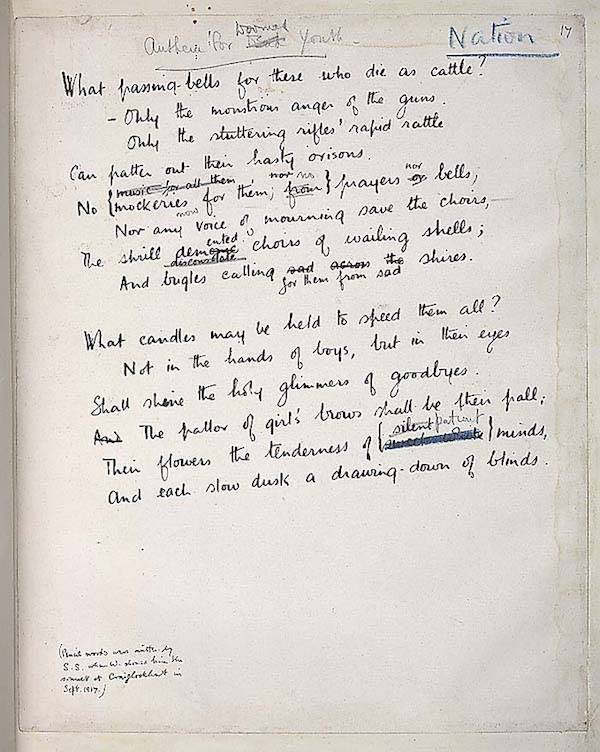

The Wilfred Owen Multimedia Digital Archive/Wikimedia Commons“Anthem for Doomed Youth” penned by Wilfred Owen, circa 1917

Wilfred Owen suffered many setbacks while fighting. He became concussed after falling into a shell hole, spending several days unconscious after a bomb detonated in his trench. He documented these experiences in letters to his mother and in reading them she was able to see his changing philosophy on war. In 1917, he was evacuated to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh after being wounded in combat and diagnosed with shell shock.

Still, he continued to fight even after he was given the opportunity to stay on home duty indefinitely after recovering from an injury. “Oh, how he hated war and all its horrors but he felt he must go out and share it with his boys,” his mother later wrote. “His nature never changed.”

While recovering at Craiglockhart, Owen met the poet Siegfried Sassoon. Owen had been interested in poetry since he was a teenager, but Sassoon became a mentor. He introduced Owen to literary figures like H.G. Wells and Robert Graves who would inspire him to write his most important poems, including “Anthem for Doomed Youth.” The poems he wrote at Craiglockhart were graphic in nature, depicting the ugliness of warfare and the grim landscape that he was surrounded by.

By then, Owen and Sassoon both believed the war should be over and that total defeat of the Central Powers would magnify the already enormous amount of casualties and suffering. Their feelings motivated their creativity, as they identified and sympathized with the soldiers in combat as well as the ones who came through the hospital.

By May 1918, Owen thought the poems he had written would speak not just to his personal experiences but would help paint a broader picture of a soldier’s life during the war. Once his service was complete, he planned to submit a manuscript to William Heinemann’s publishing company.

In June 1918, Owen returned to France, where he received the Military Cross for bravery.

Tragic Death And A Poetic Legacy Left Behind

Sadly, Owen’s manuscript would never be mailed. On Nov. 4, 1918, while leading his men across the Sambre-Oise canal, he was killed. His mother received the news one week later on Nov. 11 – the day the armistice to end the war was signed. Wilfred Owen was 25 years old.

Christopher Hall/GeographMemorial to Owen

In 1920, 23 of Owen’s poems were published in a collection that was edited by Sassoon. A review of the collection read, “Others have shown the disenchantment of war, have unlegended the roselight and romance of it, but none with such compassion for the disenchanted nor such sternly just and justly stern judgment on the idyllisers.”

In 1931, 19 more poems were published in a collection called The Poems of Wilfred Owen. In 1963, The Collected Poems of Wilfred Owen was published, containing 80 poems. He has since become one of World War I’s most influential poets, and one of the most memorable voices from the trenches.

Owen is buried at Ors Communal Cemetery in northern France. His mother chose the inscription for his gravestone from his poetry. It reads, “SHALL LIFE RENEW THESE BODIES? OF A TRUTH ALL DEATH WILL HE ANNUL.”

Next, read about the World War I Christmas Truce. Then see how Glenn Miller went from World War II’s musical icon to missing in action.