Considered a pseudoscience today, phrenology once claimed to predict a person's character and mental traits based on the shape of their head.

What if you could determine someone’s personality and mental abilities — and even their future behavior — just by touching their head? In the 19th century, phrenology promised to do just that.

Considered a pseudoscience in modern times, phrenology was once widely used as a way of understanding human behavior. Specialists would examine someone’s skull, looking for bumps and cavities, in order to ascertain if they had character traits like “secretiveness” or “benevolence.”

Though phrenology had plenty of doubters — and was sometimes horrifyingly used to promote white supremacy — this medical craze did actually touch on some truths about how brains work.

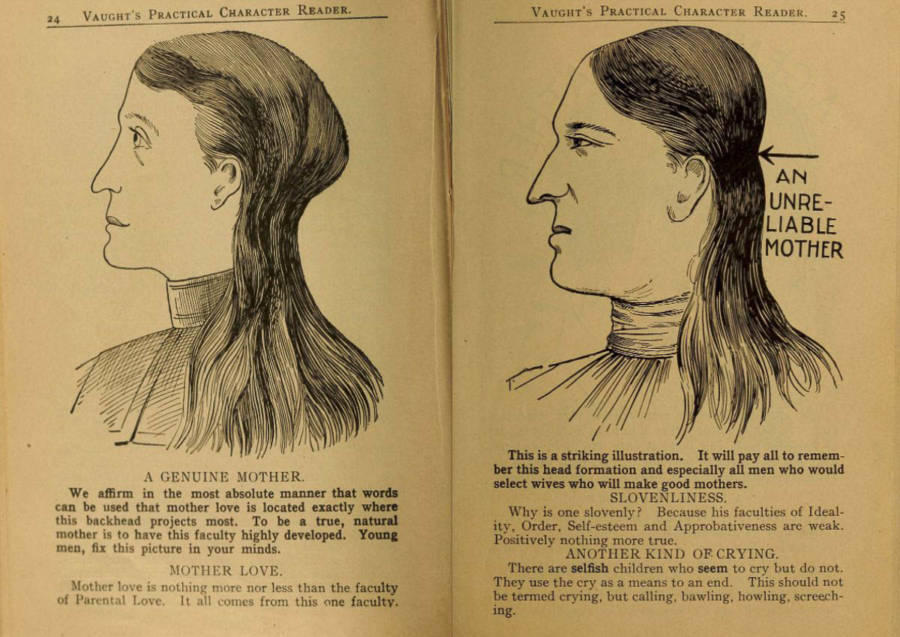

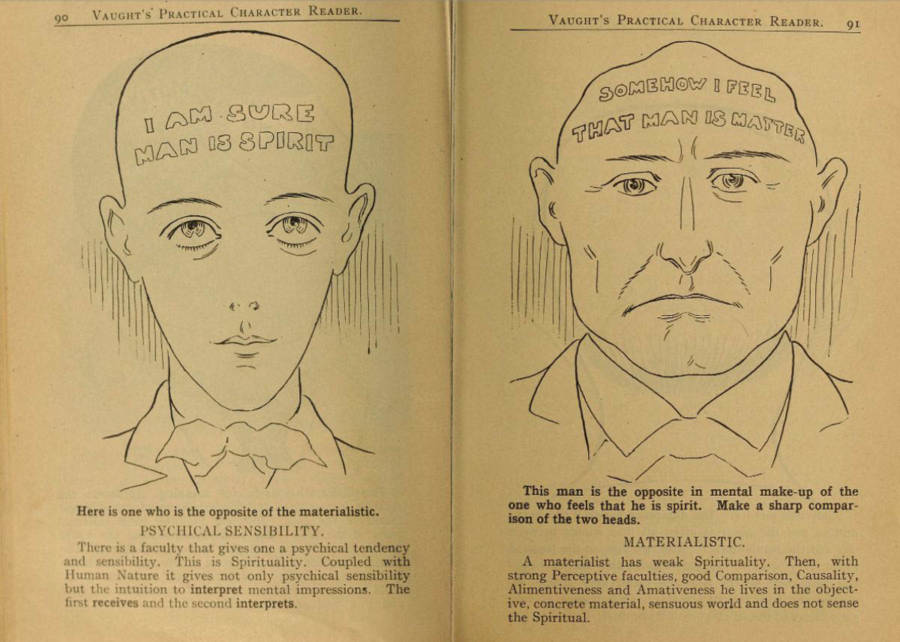

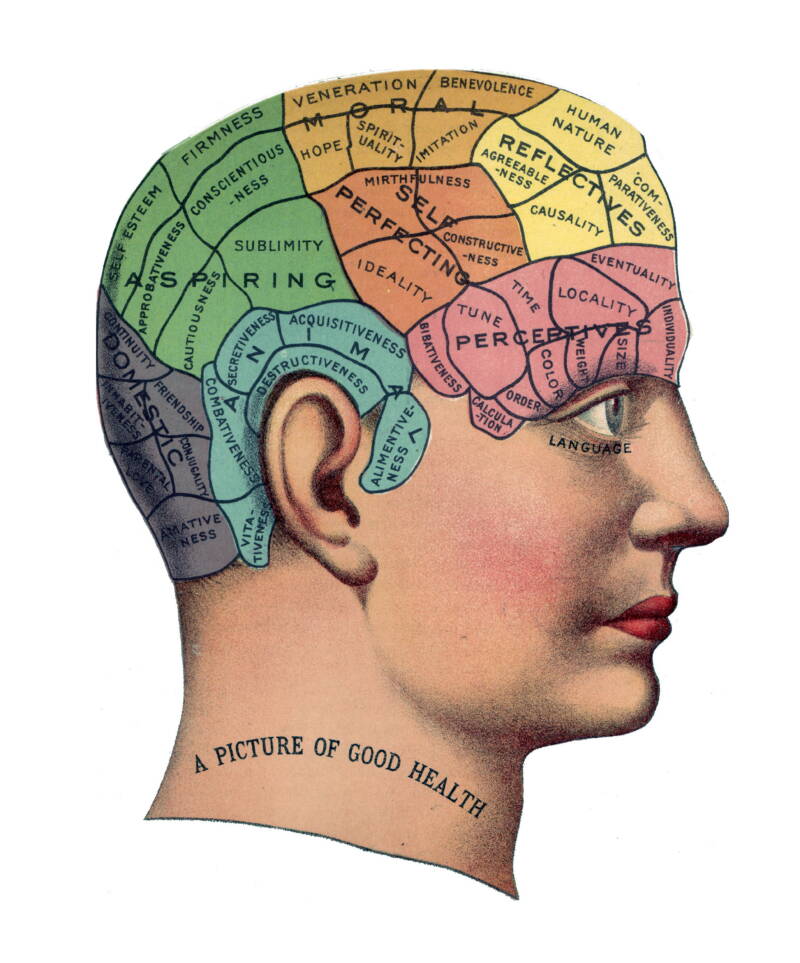

See some vintage phrenology charts from the turn of the 20th century below, then read more about the history of this now-discredited theory.

How A German Physician Invented Phrenology

As a boy growing up in 18th-century Germany, Franz Joseph Gall developed a theory about his classmates. Those who memorized facts and figures easily, Gall mused, seemed to all have large eyes and foreheads. As an adult, Gall turned this observation into a science — organology, later called phrenology.

In 1810, Gall published The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular. According to the National Park Service, Gall's book laid out his basic theory of how the brain worked. He believed that people were born with "moral and intellectual faculties," that these faculties were contained in the "organs" of the brain, and that a study of the skull could ascertain which faculties in the brain were the strongest.

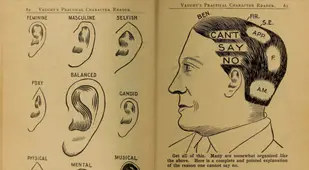

As Smithsonian Magazine reports, Gall and his protégé, Johann Kaspar Spurzheim, toured across Europe and spread their ideas. They explained to awestruck audiences that someone's personality could be determined simply by studying the bumps and crevices of their skull. Gall and Spurzheim developed a "map" of 27 faculties (later 35), which included things like hope, wonder, combativeness, destructiveness, and individuality.

DEA/BIBLIOTECA AMBROSIANA/Getty ImagesFranz Joseph Gall, the father of phrenology.

For example, the skulls of young pickpockets — according to Gall — showed a predisposition for theft. Gall found that they had bumps just above their ears, which he said were indicative of "acquisitiveness," or a tendency to be greedy, to steal, and to hoard.

Spurzheim took Gall's ideas to the United States, where they spread quickly among curious Americans. Rich and poor alike flocked to have their brains examined, including circus ringleader P.T. Barnum (who apparently lacked "cautiousness"). A postmortem examination was even conducted on a cast of Aaron Burr's skull, which found that the infamous former vice president had large faculties for "secretiveness" and "destructiveness."

When future U.S. President James A. Garfield visited a prominent phrenologist in 1854, he recorded the experience in his journal:

"He said I was inclined to be mentally lazy, and had never called out my powers of mind, that they were greater than I supposed. He told me to elevate my standard of aspiration and thought. I had better aim at the Judge's Bench. Said I needed to be more spirited in resenting an insult."

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesA phrenology chart from 1859, mapping out the various "faculties" of the brain.

But not everyone believed in phrenology. Mark Twain wryly noted that his examination had found that he lacked "humor." And former president John Quincy Adams wrote in an 1839 letter: "I have never been able to prevail upon myself to think of [phrenology] as a serious speculation."

But although phrenology may seem harmless, it was also seized upon by pro-slavery advocates who argued that it supported white supremacy.

The Dark Side Of Phrenology

Though phrenology was, for many Victorians, something of an amusing parlor game, it also became a tenet of scientific racism. As The Guardian notes, pro-slavery advocate Charles Caldwell was a phrenologist from Kentucky who used his "study" of skulls to justify the enslavement of Black people.

According to his phrenological research, Africans supposedly had large faculties for "veneration" and "cautiousness." This, Caldwell decided, made them "tameable." He wrote in an 1837 letter to a correspondent: "Depend upon it my good friend, the Africans must have a master."

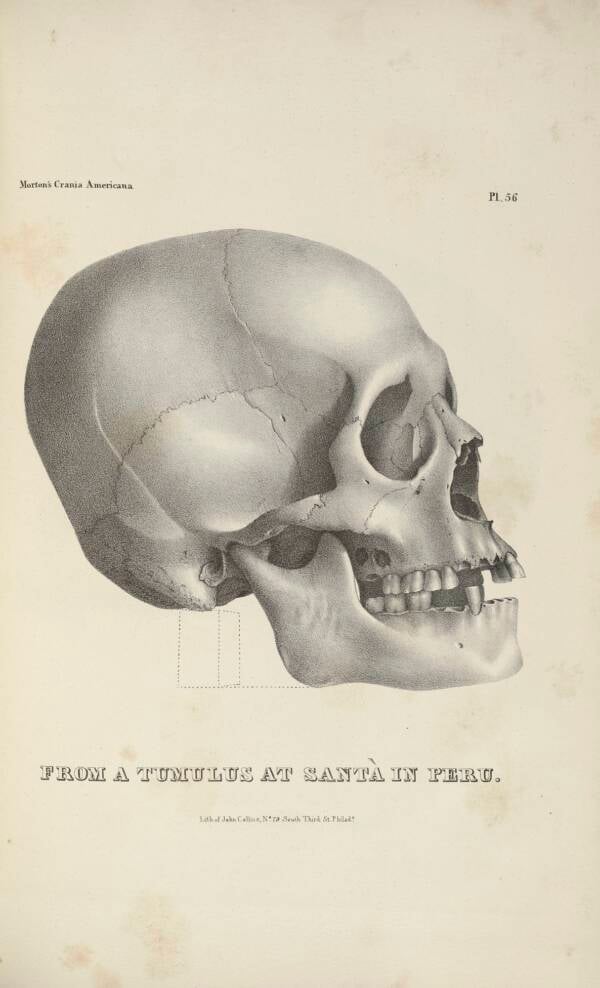

Caldwell wasn't the only person to use phrenology to justify white supremacy. Many phrenologists accepted the work of Samuel George Morton, whose Crania Americana (1839) examined skull differences between various races of people. Among other things, Morton declared that the minds of Native Americans "[appear] to be different from that of the white man" and that they were "adverse to cultivation, and slow in acquiring knowledge."

Public DomainA skull featured in Morton's Crania Americana, in which Morton pointed out alleged differences between skulls from various races. His conclusions were used by some, including phrenologists, to justify white supremacy.

According to Cambridge University, phrenologists promoted Morton's ideas, thus turning the study of the skull into a way to justify the forcible relocation and the subjugation of Native American people.

But not everyone who believed in phrenology was looking to enslave Black people or push Native Americans away from their land. Curiously, some anti-slavery advocates also accepted many phrenological teachings. As The Guardian reports, abolitionist Lucretia Mott raved about the "truth of phrenology." Likewise, Scottish phrenologist George Combe, who was adamantly anti-slavery, also accepted and endorsed the pseudoscience.

Anti-slavery advocates like Mott and Combe came to the same conclusion as people like Morton and Caldwell — that phrenology proved that Africans were meek and easily controlled. But while Caldwell used this to justify slavery, Mott and Combe used it to justify abolition.

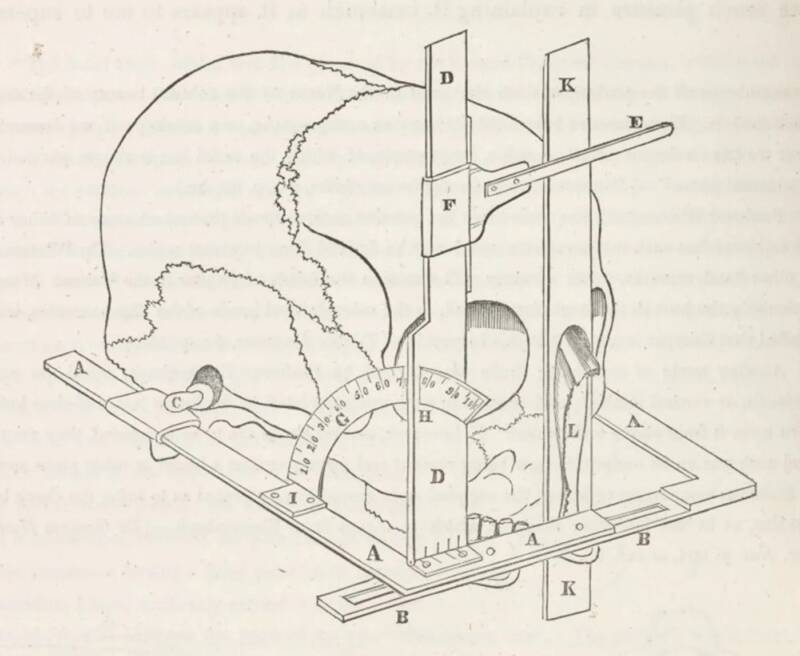

Public DomainA "Facial Goniometer" from Crania Americana, which Morton used to study skull shapes and sizes.

"The qualities which make them submit to slavery are a guarantee that, if emancipated and justly dealt with, they would not shed blood," Combe argued, effectively stating that white Americans had nothing to fear from freeing "submissive" enslaved Africans in the United States.

He and Mott believed that society should help "weak" Africans instead of enslaving them. And they used phrenology to suggest that if enslaved Africans were freed, they could easily be molded into white society.

All of this is, of course, bunk. And phrenology is seen today as a pseudoscience akin to palm reading. But early phrenologists like Franz Joseph Gall did actually touch on some truth about how the brain functions.

How This Pseudoscience Touched On Some Scientific Truth

Today, scientists don't believe that the brain is divided into 35 different sections that control behavior like "combativeness," "self-esteem," and "hope." But ideas from phrenology have found their way into modern medicine. Just consider the historic case of Phineas Gage.

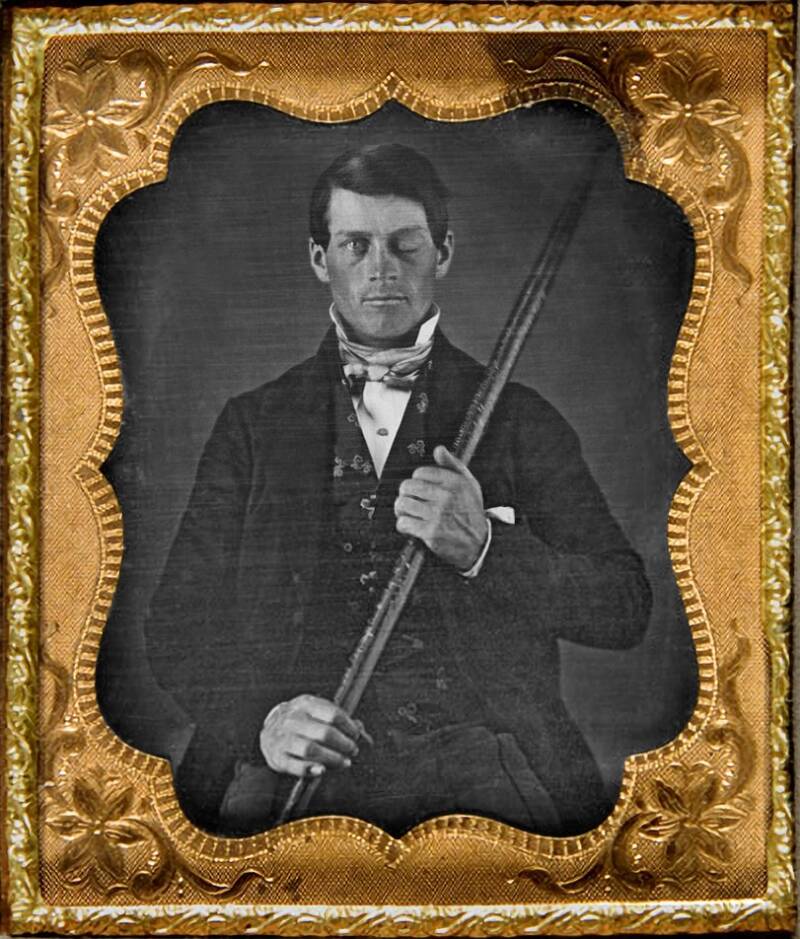

Gage miraculously survived an accident in 1848 that by all accounts should have killed him. While working on a railroad in Cavendish, Vermont, an explosion shot an iron bar straight through his brain, entering under his cheekbone and exiting at the top of his head.

To the shock of all, Gage was able to speak and even walk mere moments after the accident. But after doctors patched him up, Gage seemed to become a different person. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the once gentle Gage started picking fights, exhibiting irresponsible behavior, and cursing to such an extent that women were advised to avoid him.

A phrenologist who examined Gage concluded that the change in his personality could be explained by the area of the brain where he was injured. The iron bar, the phrenologist said, had caused damage "in the neighborhood of Benevolence and the front part of Veneration" of Gage's skull.

Originally from the collection of Jack and Beverly Wilgus, and now in the Warren Anatomical Museum, Harvard Medical SchoolPhineas Gage with the iron bar that shot through his head in 1848, dramatically altering his personality. Phrenologists declared that his "benevolence" and "veneration" organs had been damaged.

About 20 years later, a young neurologist named David Ferrier, who was studying localized areas of brain function, commented that Gage's case seemed to support some ideas from phrenology. "The phrenologists have, I think, good grounds for localising the reflective faculties in the frontal regions of the brain," he noted.

Indeed, the Gage case provides an interesting connection between phrenology and neuroscience. Phrenologists might have said that the bar damaged Gage's "benevolence"; modern-day neuroscientists would note that it damaged his frontal lobe, which can cause behavior changes.

Thus, though phrenology itself has long been disproven, this fascinating pseudoscience lay the groundwork for future research into neuroscience. It inspired scientists to explore different parts of the brain and how they work — something that's still studied to this day.

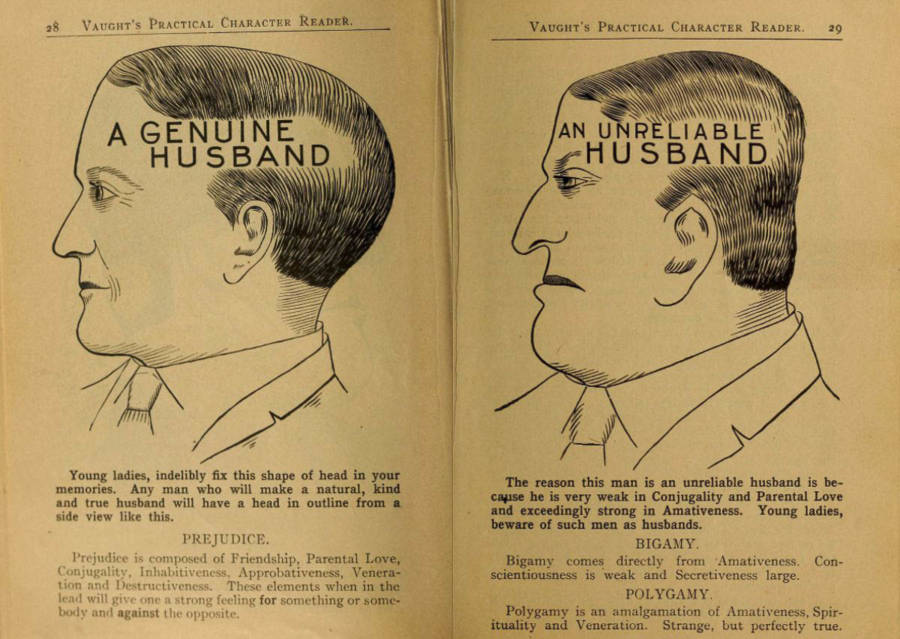

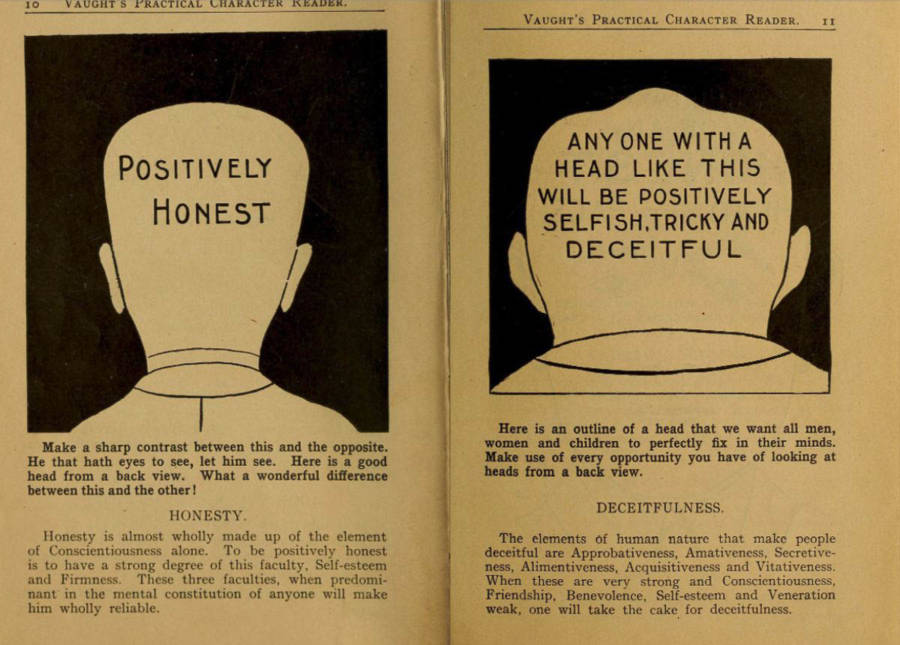

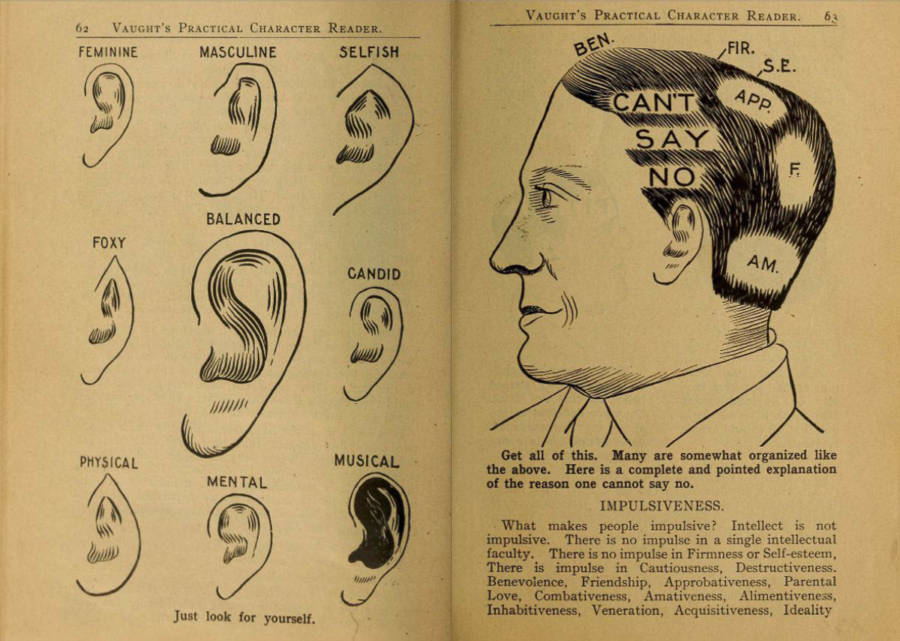

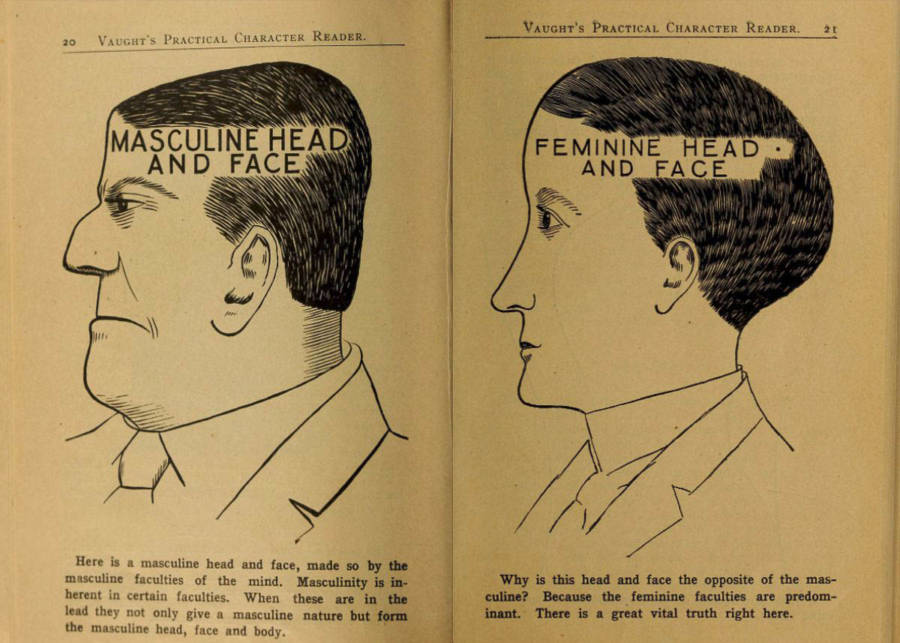

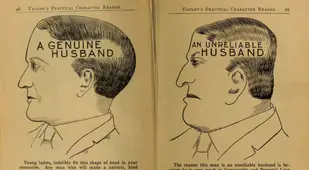

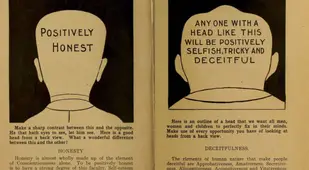

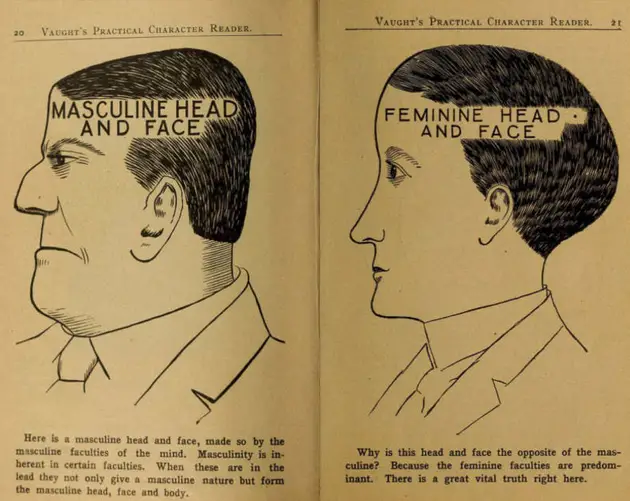

In the gallery above, look through some vintage phrenology charts and diagrams from Louis Allen Vaught's 1902 phrenology handbook Vaught's Practical Character Reader. Though phrenology has been debunked, it's fascinating to see what people once thought certain skull shapes could tell us about someone's loyalty, masculinity, honesty, and more.

After this look at phrenology charts, see some disturbing photos that reveal the history of eugenics. Then, look inside the "Psychopathia Sexualis," the 19th-century books that experts once used to explain sexual deviancy.