The welfare state gets a lot of criticism, but what seldom comes up is how things used to be before programs like SNAP and Section 8 came along.

Wikimedia Commons

According to the United States Census Bureau, in 2015 a full 52.2 million American households participated in some kind of means-tested welfare program. That’s more than 21 percent of the U.S. population, most of whom have children under the age of 18 to take care of.

The majority of assistance came in the form of food aid and subsidized health insurance, although a sizable number took part in multiple programs. The bulk of people stay on these programs for between three and four years before rising out of the income bracket that qualifies for aid. Another 60 million Americans currently receive Social Security pensions in one form or another, whether for old age, disability, or survivor benefits.

These programs get a lot of heat, and cutting the levels and accessibility of so-called “entitlements” has been a conservative talking point for decades. With a majority of states, plus Congress and the White House, now coming under Republican control, it’s likely that these programs will fall under review soon and see some big changes.

Before the debate starts, however, it may be a good idea to have a look at how things used to be, before the New Deal and Great Society programs radically altered the way America treats the economically vulnerable.

Food Stamps

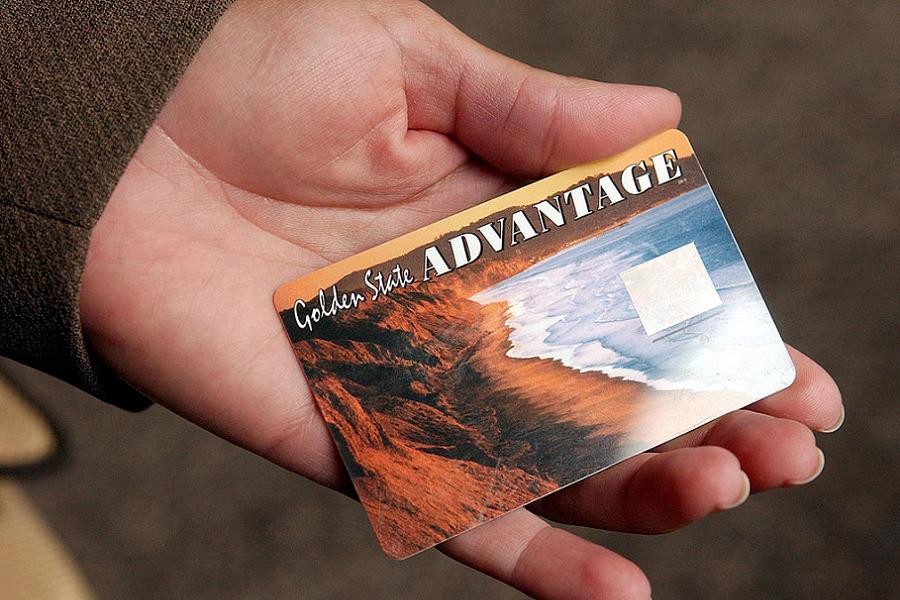

Justin Sullivan/Getty ImagesDeborah McFadden holds a sample of the new California State Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) card on July 17, 2002 in Oakland, California.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), or “food stamps,” is one of the most popular and successful government aid programs in history.

Geared primarily toward families with minor children, SNAP benefits feed 47 million people a month at an annual cost of $74 billion. The average household on the program gets around $250 a month that can only be spent on food from approved retailers. Various subsidiary programs, such as subsidized school breakfasts and lunches, pick up more of the slack for households with school-age kids.

In addition to feeding hungry children, SNAP benefits have an economic multiplier effect; government economists estimate that every dollar disbursed in food stamps almost immediately adds $1.84 to the national GDP because of how the benefits are injected right into the local economy as soon as they’re received. In 2012, an ambitious budget proposal in Congress threatened to cut SNAP by half, but opposition from the Obama White House blunted the effort.

Loch Haven BooksChildren stand in line for charity meals during the Great Depression.

Before food stamps, which were first issued as an emergency measure in 1939 and permanently after 1964, poor Americans were basically out of luck if they couldn’t afford food. The problem here wasn’t that children would necessarily go hungry – though that did happen – but instead that grocery budgets cut into rent and other expenses, forcing cuts elsewhere so that a family could put food on the table.

Worse, from a macroeconomic point of view, the Great Depression had created a major imbalance in the market: While unemployed people tightened their belts and held off buying food, surplus food rotted on the shelves, unsold. This forced a contraction of the agricultural sector and increased unemployment even among unskilled and immigrant labor, making the Depression even worse than it already was.