From feminism to a life-saving act as simple as washing your hands, some advanced ideas were just too big for people to handle at the time.

Suffragists parade down Fifth Avenue, 1917. Image Source: The New York Times Photo Archives

On January 10th, 1878, California senator Aaron Sargent proposed a constitutional amendment that would grant women the right to vote. It would take 42 years to pass, finally happening in 1920. The amendment—like those behind it—was one of many advanced ideas whose primary flaw was that it was simply ahead of its time.

In honor of the 19th Amendment’s passing, we look back at other ideas, figures and inventions which came before most people were ready for them.

Hand Washing

While commonplace today, a doctor in the 19th century lost his job for recommending it. Image Source: Flickr

While it’s common knowledge these days that hand washing is the best defense against pretty much any germ with which you could possibly come into contact, it didn’t really start to catch on with doctors until the mid 19th century. In fact, the words of the doctor who first told his students to wash their hands proved so controversial that he lost his job over it.

While working in a Vienna maternity clinic in 1847, Dr. Ignaz Semmelweis noticed a disturbing trend: new mothers were dying in droves due to some mysterious ailment known as “childbed fever.”

Semmelweis resolved to figure out what was behind these deaths, and started by looking for disparities between the hospital’s two maternity wards. Midwives managed one ward, with male doctors and medical students in charge of the other. Semmelweiss found that the women treated by the latter were dying at a rate nearly five times that of those in the midwives’ clinic.

When a pathologist operating in the latter ward died of childbed fever, the Hungarian doctor got his most important clue to solving this puzzle. The major difference between the doctors and the midwives was that doctors performed autopsies in addition to delivering babies — and often, they went straight from one procedure to the next.

When Semmelweis figured this out, he realized that the doctors were spreading material from dead bodies to maternity ward patients. If he could prove that this was the route of transmission, he could likely stop the spread of the fever.

Semmelweis then pioneered disinfection measures, mostly using chlorine (which he thought would do well to cover up the smell of death). When the rate of childbed fever dropped dramatically, he realized that the answer had been pretty simple all along: the maternity ward needed to be kept clean, and doctors needed to wash their hands.

Doctors at the ward resisted his attempts to impose these measures, however, mostly because they felt they were being blamed for the mothers’ deaths. They soon stopped washing their hands and disinfecting and, sure enough, childbed fever returned.

Semmelweis eventually lost his assignment at the ward, and abruptly left Vienna in 1850. Over time, the man went insane and was committed to an asylum. The irony? Some historians believe he died of sepsis—the same thing that killed all those women on the maternity ward. He was 47 years old.

Peak Oil

One scientist predicted the U.S. hit peak oil in the 70s — and was right. Image Source: Flickr

Discussions of transitioning away from fossil fuels all but dominate climate politics today, but one person in particular tried to get the conversation started over half a century ago.

In 1956, geologist and statistician M. King Hubbert presented his disconcerting research findings at an American Petroleum Institute meeting. During the meeting, he warned that within just twenty years the U.S. would reach what he called peak oil consumption. In Hubbert’s eyes, in any given area, the rate of petroleum production from an oil reserve would resemble a bell curve: this essentially meant that by the early 1970s, the U.S. would hit the height of petroleum production in its preserves, and future production rates would fall.

No one wanted to hear it. In post-WWII America, the economy was booming, gas was cheap and car ownership was on the rise. Likewise, other predictions on oil capacity—which based their predictions on reserves-to-production ratios, not future discoveries, like Hubbert’s—had proven false. While it was understood that oil was a finite resource, the belief stood that there was so much of it that it wasn’t worth worrying about what we’d do when it eventually dried up.

Hubbert was not only widely criticized for his research, but more or less laughed out of the industry. He was all but forgotten about until 1970 — when his prediction proved correct. At around that time, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) placed an oil embargo on the U.S., sending the nation into an energy crisis.

Hubbert believed, as many contemporary scientists do, that renewable energy must replace fossil fuels to create sustainable energy not just in the U.S., but the world. He died in the late 1980s, but his prediction about the world reaching peak oil in 1995 was not completely far off: current predictions estimate that 2020 will be the year peak oil is reached on a global scale.

Christine de Pizan

Christine de Pizan depicted presenting her collected works to the Queen of France, Isabeau de Bavière, sometime between 140 and 1415.

The Medieval era might not conjure too many images of feminism, but some scholars argue that Christine de Pizan was one such feminist. When she was widowed at age 25 (after ten years of marriage) de Pizan needed to find a way to support herself. In late 14th century Venice, there weren’t many ways for a woman to be self-sufficient, but Pizan had an upper hand since, unlike most women of her time, she had an education and was able to write.

It might seem far-fetched that anyone could support their mother, children and extended family on a writer’s income, but that’s what Pizan managed to do—in fact, she was the first woman in all of Europe to make a living as a professional writer.

She wrote across several genres, styles and topics and created some of the first feminist manifestos, though many of her advanced ideas were (and perhaps still are) ahead of society in that regard. During her lifetime her work was appreciated in small circles, enough for her to make money from commissions, but she was never the literary sensation she could have been as a feminist icon.

Her most important work, The Book of the City of Ladies, was written specifically to call out society’s perception of women as lesser beings. The book, published in 1405, honored great women in history and elevated them to the same level as their male contemporaries. Unfortunately, many women of Pizan’s time would not have had access to the tome or have been able to read it, leaving it to be consumed primarily by the upper echelons of society—an audience which could appreciate Pizan’s commentary on aristocracy, fashion and chivalry.

While many contemporary scholars and writers believe that Pizan should be considered a feminist writer, many also argue that to call her such would be an anachronistic use of the word and a misinterpretation of her intentions as a writer.

Telegraphy

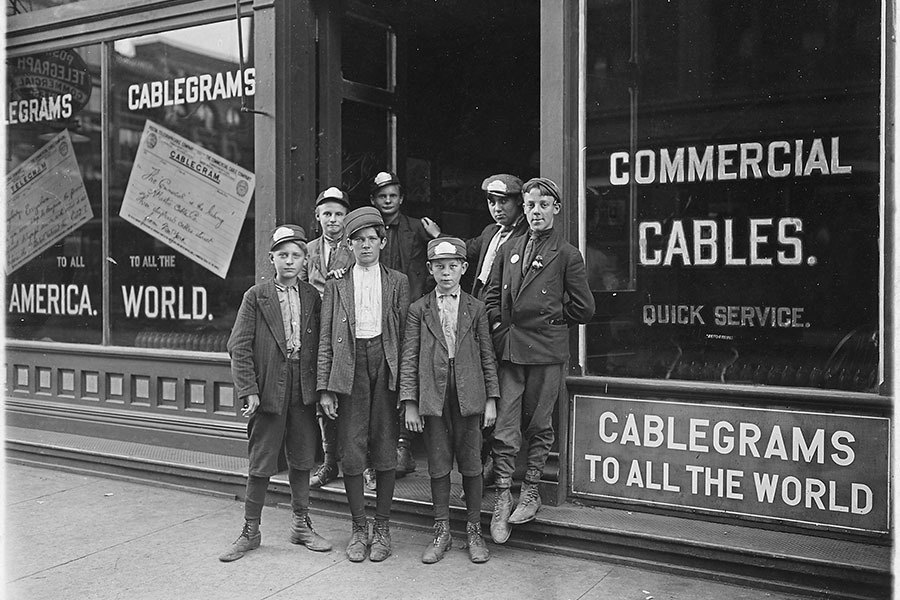

Postal telegraph messengers in the 1930s. Image Source: Wikipedia

The idea of long-distance communication predates the cell phone and even the internet. As soon as people started traveling long distances, the thought of a more immediate method to communicate with loved ones back home became more and more enticing.

This idea came to fruition in 1823, when Francis Ronalds constructed an electrostatic telegraph spanning eight miles of wire. Insulated in glass tubing, Ronalds laid down the wire and connected both ends to clocks marked with the letters of the alphabet. Electrical impulses sent along the wire transmitted messages. While Ronalds’ invention was acknowledged when he published an account of it, years would pass before the technology truly flourished.

While this ultimately helped give rise to Morse Code, it would take the work of another “no name” to bring the technology one step closer to life.

In 1832, a Russian diplomat named Pavel Schilling devised a small telegraph system that could send a message using the binary system of transmissions. The problem for Schilling was length—he could only transmit messages between two rooms in his small St. Petersburg apartment. While Schilling’s idea didn’t take off, he was the first person to ever use the binary system, later be used to develop Morse Code, which was born in the U.S. in 1838.

The Inventions Of Jules Verne

A depiction of the underwater vehicle in Verne’s “Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea”

Today’s steampunk subculture immortalizes many elements that appeared in 19th century science fiction author Jules Verne’s novels. But what is most impressive is how so many ideas Verne had in his books came to fruition well after Verne created them.

In his most famous work, Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, the submarine captained by the salty Captain Nemo far surpassed early prototypes of the invention itself. Indeed, it would take decades to reach the level of majesty Verne envisioned.

In Robur the Conqueror, the main character constructs an aircraft from a strong, but lightweight, material called pressboard, which used rotors to fly. Verne took the first prototypes for what we now refer to as heliocpters and expanded on them, predicting the ways in which they would develop.

Most famously, in From the Earth to the Moon, Verne predicted that one day man would set foot on the moon. While Verne’s means of getting a character there (via a cannon) were not particularly scientific, his idea to send man to the moon predated the actual moon landing in 1969 by more than a century.

Next, see five inventions made by Leonardo da Vinci that changed history forever.