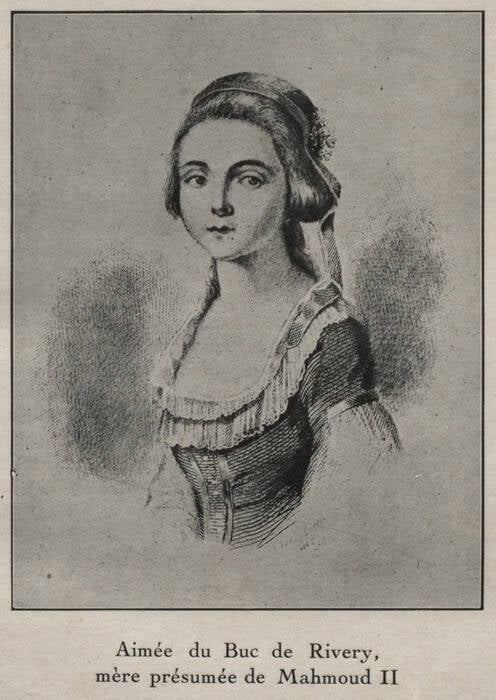

When Aimée du Buc de Rivéry disappeared at the end of the 18th century, people speculated that she may have somehow become the Sultana Valide of the Ottoman Empire. But could this be true?

Wikimedia CommonsThe french planter-heiress has been conflated with a sultana of the Ottoman Empire named Nakşîdil.

When Aimée du Buc de Rivéry went missing at sea, legend filled the gaps in her story. It was rumored that she was captured by pirates, sold into slavery, and chosen as a sultan’s favorite concubine. From there, she became the sultana of the Ottoman Empire.

Historically, Aimée du Buc de Rivéry was born on the Caribbean island of Martinique to a wealthy planter. She was a relative of Empress Josephine, Napoleon Bonaparte’s beloved wife, and she did inexplicably disappear on a boat in 1788 — or 1778, depending on the source.

Without information to describe how she vanished, a legend naturally arose and Aimée du Buc de Rivéry was conflated with an Ottoman sultana named Nakşidil, who was rumored to have French origins.

But how likely are the rumors that a Martinican planter-heiress could come to lead one of Europe’s most powerful empires through a series of unbelievable events?

Aimée Du Buc De Rivéry, A Martinican Queen

“I ran, I jumped, I danced, from morning to night; no one restrained the wild movements of my childhood,” wrote Marie Josèphe Rose Tascher de La Pagerie, later Empress Josephine of France, about her childhood in Martinique.

Her cousin Aimée du Buc de Rivéry would probably have testified to having had a similar upbringing.

Wikimedia CommonsEmpress Josephine and Aimée du Buc de Rivery likely experienced similar childhoods in the French Caribbean.

Born in 1768 to wealthy French sugar farmers in Pointe Royale, in the French colony of Martinique, Aimée du Buc de Rivery likely enjoyed a relatively unconstrained and relaxed childhood.

The jungles and creeks of the island were likely her playgrounds, the same way they were for Empress Josephine.

It has been suggested that the girls socialized while growing up in Martinique. According to The Rose of Martinique: A life of Napoleon’s Josephine, by Andrea Stuart, a fortune-teller came to the island and predicted the futures of the two girls.

Josephine’s prophecy maintained that she would someday “regret frequently the easy, pleasant life of Martinique,” but would have the consolation prize of marrying a “dark man of little fortune” who would bring her to a status “greater than a queen.”

Rivéry’s fortune was perhaps even more intriguing: She would be kidnapped by pirates and sold to a “grand palace” on the other side of the world. The fortune-teller allegedly continued: “At the very hour when you know your happiness is won, that happiness will fade like a dream, and a lingering illness will carry you to the tomb.”

Of course, these readings seem like convenient foreshadowing, but according to Stuart’s book, Empress Josephine would refer to this incident in later years, suggesting that it may have actually happened.

From French Heiress To Sultana

Wikimedia CommonsNakşidil, the sultana often believed to be Aimée du Buc de Rivéry.

It seems most aspects of Rivéry’s life are in contention. Some accounts claim that she disappeared in an ocean crossing in 1778, just a year before Empress Josephine’s own crossing that ultimately brought her to the throne.

Other accounts claim she disappeared in 1788 after leaving a French convent and was kidnapped by Barbary pirates. Another legend says she was kidnapped as early as age two and a fourth that she drowned in a shipwreck.

Most of the legends conflate Rivéry with Nakşidil, wife of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid I and the mother of Sultan Mahmud II of the Ottoman Empire. When Nakşidil died in 1817, the mother-in-law of the French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire wrote:

“It is said that the deceased sultana was French…that at barely two years old, her parents embarked with her to America and they were captured by a corsair who took them to Algiers, where they perished…She was sent to Abdul Hamid, who found her beautiful and elevated her to the rank of Kadine…She gave him Mahmud, the reigning sultan. Mahmud has always had a great respect for his mother. It is said that she has greatly surpassed in amiability the Corsicans or the Georgians which is not surprising since she was French.”

This account was noted in Royal French Women in the Ottoman Sultans’ Harem: The Political Uses of Fabricated Accounts from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century by Christine Isom-Verhaaren.

Wikimedia CommonsNakşidil’s husband, Sultan Abdul Hamid I.

According to this account, Rivéry and the Sultana were actually one and the same. After being sold into slavery from pirates as a child, Rivéry was chosen to enter the sultan’s harem because of her beauty. From there, she charmed the sultan and gave birth to his son, the future sultan, Mahmud II.

As the mother of the next sultan and holding great clout, Rivéry was said to have created a rococo palace in the Ottoman Empire and instilled French values in her son, Mahmud II.

That son would go onto become someone like the Ottoman’s version of Peter the Great. As a progressive sultan, Mahmud II installed a cabinet in his government and created a post office system.

The Power And Persistence Of A Rumor

In the 1860s, Sultan Abdul Aziz, Mahmud II’s son, mentioned to the press on a visit to Paris that his grandmother and Napoleon III were related. This further underscored the rumors that Rivéry and Nakşidil were the same woman. But why, exactly, did this theory have so much traction in its time?

The answer, it seems, is politics. From the perspective of the Ottoman Empire, creating a French connection was just good foreign policy. For the French, the rumor reinforced Napoleon III’s claim to royalty because he was not from a traditionally royal line.

But actually, the conflation of a wealthy French planter-heiress and a sultana didn’t even begin with the story of Rivéry and Nakşidil. Since the 16th century, there was a rumor that a French princess had married into the royal Ottoman family.

Wikimedia CommonsSultan Mahmud II, the son of Nakşidil.

Selaniki, a late 16th-century Ottoman administrator, was the first on record to suggest that there was a link between the royal families of France and the Ottoman Empire. He claimed that the French king was “Our prince, and of our race.”

It was thus convenient to conflate a lost French heiress named Aimée du Buc de Rivéry with a sultana in order to solidify political relations and merge the two kingdoms.

Unfortunately, it is extremely unlikely if not impossible, that Aimée du Buc de Rivery was the sultana valide. The dates of her disappearance and Mahmud II’s birth do not line up, and what’s more, there’s proof that Nakşidil came from the Caucasus, not France by way of Martinique.

However, the romance between a planter-heiress-turned-slave and a sultan has proved powerfully intoxicating.

For more royal myths, check out Anna Anderson, the whoman who claimed to be the lost Grand Duchess Anastasia. Then, read up on the true story behind Shakespeare’s Henry V.