Though Albert DeSalvo confessed to murdering 13 women in the early 1960s, some believe that the "Boston Strangler" was really multiple serial killers.

On July 8, 1962, readers of the Sunday edition of the Boston Herald opened their papers to a shocking headline: “Mad Strangler Kills Four Women in Boston.”

The article warned that a “mad strangler is loose in Boston” who has “slain four women during the past month.” Several women in the greater Boston area called the police in a panic, saying a man claiming to be “The Strangler” had called their homes to tell them “You will be next.”

Getty ImagesSelf-confessed Boston Strangler Albert DeSalvo stands in jail for an unrelated crime.

Boston already had cause to panic. But it couldn’t predict just how bad things would get. The “Mad Strangler” — also dubbed a “Phantom Fiend” and “Phantom Strangler” by the local press — wasn’t done yet. Between June of 1962 and January of 1964, 13 women would turn up dead, allegedly at the hands of the same culprit.

One man named Albert DeSalvo eventually confessed to all 13 murders, and many assumed the investigation was complete. But the truth of the man’s confession has been disputed for decades.

Was there really only one Boston Strangler? Or were the 13 killings the work of more than one murderer?

The Boston Strangler’s Crimes

The victims of the Boston Strangler were all single women, but their profiles were quite different otherwise. One was just 19 years old, while the oldest victim was 85. Some lived in Boston, but others lived miles north in Salem, Lynn, and Lawrence. They were students and seamstresses, widows and divorcées.

Getty ImagesThese file photos show eight of the victims of the Boston Strangler. The women are (upper L to lower R): Rachel Lazarus, Helen E. Blake, Ida Irga, Mrs. J. Delaney, Patricia Bissette, Daniela M. Saunders, Mary A. Sullivan, Mrs. Israel Goldberg.

From the start, police theorized that likely one person committed the crimes.

So many aspects of the crimes pointed to a single modus operandi: The women were almost invariably raped and strangled, usually with nylon stockings. Many were killed in the middle of the day. The victims would be lying naked on top of their bedcovers for the police to find.

Oddly, the Strangler didn’t appear to have broken into any of the victims’ homes. That led police to believe that the women had known their attacker. More likely, the women had believed that he was someone they could trust or had expected to arrive. The perpetrator may have dressed up as a repairman or delivery person.

The Next Chapter

Though the public referred to the mysterious culprit as the Boston Strangler, a fair amount of the crimes took place outside the Boston city limits.

This complicated things for the Boston police, as well as Suffolk County prosecutors. Massachusetts Attorney General Edward Brooke, who later became the first African-American to be popularly elected to the U.S. Senate, stepped in to coordinate police efforts.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesPolice check a roof near the Boston apartment where 19-year-old Mary Sullivan was found strangled to death. She was the Boston Strangler’s thirteenth victim. January 4, 1964.

Months went by, thousands of suspects were interviewed, and the police — and the public — were desperate for a breakthrough.

At the request of a group of private citizens who volunteered to pay the expenses, the police enlisted the help of Peter Hurkos, a Dutchman who claimed to possess extrasensory perception, or ESP. In a prepared statement, Brooke called Hurkos’s talent “psychometry.”

Hurkos — who also lent his services to the Manson Family murders investigation — looked at crime scene photographs, declared that all of the murders were perpetrated by the same individual, and even pointed police to one suspect. Police took that suspect into custody but found that he was too mentally deranged to stand trial.

In the meantime, women in Boston made sure to lock their doors. They bought chains, deadbolts, and pepper spray. Police stations were inundated with calls from women who received unwelcome knocks on their doors or suspicious phone calls. Some even moved out of the city.

“What do you do about the door when you enter?” one woman asked The Atlantic:

“You look in the closets, under the bed, and in the bathroom. If a man is in there you want to be able to run out, screaming for help. Therefore, you should leave the door open. But if you leave the door open while you are making a search, what is to prevent the Strangler from following you in and standing between you and your means of escape when you first see him? Do you enter the apartment, lock the door, and then start searching; or do you leave the door unlocked, or open, and make a hurried search?”

A Suspect Emerges: Albert DeSalvo

Getty Images Albert H. DeSalvo (left), the self-confessed “Boston Strangler,” is escorted into Middlesex County Superior Court.

Fear of the Boston Strangler consumed the whole city. Though the police were on high alert for one type of bad guy, others still flourished. One such criminal was the “Green Man,” who had begun his crime spree in Boston and then moved on to terrorize cities in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Hampshire.

Authorities believed the Green Man, whose nickname came from the green clothes he’d wear while committing his crimes, committed more than 400 burglaries and sexually assaulted more than 300 women. At the same time that a task force was investigating the Boston Strangler, one was also looking for the Green Man.

In October of 1964, a 20-year-old Cambridge woman reported her sexual assault to the police. She told them that she’d woken up to find a man in her bedroom. Wielding a knife, he tied her up and molested her. After she complained that her bonds were too tight, he loosened them.

After helping the police produce a sketch of her attacker, the authorities noticed similarities between him and another criminal who had a history of sexual deviance.

Wikimedia CommonsAlbert DeSalvo in 1967.

The criminal’s name was Albert DeSalvo, but to the police, he was the “Measuring Man.” The Measuring Man’s crime spree began in the late 1950s. He’d go door to door looking for young women and introduce himself as a talent scout from the “Black and White Modeling Agency.” He’d ask to take their measurements and fondle them while doing so.

In 1960, cops arrested DeSalvo while he was breaking into a woman’s home, and he admitted to being the Measuring Man.

From The Green Man To The Boston Strangler

For his crimes as the “Measuring Man,” Albert DeSalvo received 18 months in prison for his crimes. He was ultimately released for good behavior after serving just 11. After he got out of prison, he fell off of the police’s radar.

Enter the Green Man’s last victim. Following that woman’s report, police pinned DeSalvo to the crime and published his photo in the paper. Immediately several more women came forward to identify DeSalvo as their attacker.

Arrested on a single rape charge, DeSalvo was sent to the Bridgewater State Hospital, where he met fellow inmate and convicted murderer George Nassar.

One day in February 1965, Nassar called his attorney, F. Lee Bailey – who later gained notoriety for helping defend O.J. Simpson in the 1990s — and asked him if the Boston Strangler could “make some money” from publishing his story. Bailey asked him what he meant, and Nassar told him about DeSalvo.

In an interview in the hospital’s psychiatric ward, Albert DeSalvo admitted on tape to being the Boston Strangler.

Albert DeSalvo: The Boston Strangler… Or Not?

Albert DeSalvo may have confessed to the rapes and killings of the Boston Strangler, but many people doubted his guilt from the beginning.

Ollie Noonan/The Boston Globe/Getty ImagesAlbert DeSalvo is captured by police in Lynn, Massachusetts, after escaping prison. February 25, 1967.

For starters, though he was able to recount the crime scenes in great detail, not a shred of physical evidence tied him to the crimes. His timeline matched up with the Boston Strangler murders — DeSalvo was released from his first bout in prison mere weeks before the first Strangler killing — but he seemed like the kind of person who would have admitted to the murder spree upon his initial capture.

According to forensic psychiatrist Ames Robey, DeSalvo was “a very clever, very smooth, compulsive confessor who desperately needs to be recognized.”

Despite the fact that he may or may not have done it, DeSalvo was able to describe each crime in such detail that his own lawyer was convinced of his guilt. But despite their hopes of closing the case, many detectives and prosecutors believed DeSalvo’s confession was a sham.

In 1967, Albert DeSalvo went to prison for the Green Man crimes, though he never stood trial for those relating to the Boston Strangler. He ended up escaping jail for a short period and being transferred to a maximum-security prison a few years later.

Some have suspected Nassar’s the real Boston Strangler, and that he convinced DeSalvo to confess to the killings so they could split whatever money he could milk from the publicity.

“Even when Richard, his own brother, went to see him, Nassar was always there and Albert wouldn’t speak without his permission,” Elaine Sharp, who represented DeSalvo’s relatives, told The Guardian.

During one of Richard’s visits, his brother leaned toward him and asked, “Do you want to know who the real Boston Strangler is? He’s sitting right here.”

“Nassar’s face turned to stone,” Sharp says.

In 1973, DeSalvo was found stabbed to death in his cell. His killer – or killers — were never identified.

With the death of Albert DeSalvo and no further leads, it appeared that no one would ever really solve the Boston Strangler case.

The Boston Strangler Case Solved After Decades

For the next 46 years, the case of the Boston Strangler remained open. There were apparently no more victims, either.

Then, in 2013, the police had a breakthrough. Using DNA found on a water bottle belonging to DeSalvo’s nephew, Tim, police were able to link the final Boston Strangler victim, 19-year-old Mary Sullivan, to Albert DeSalvo.

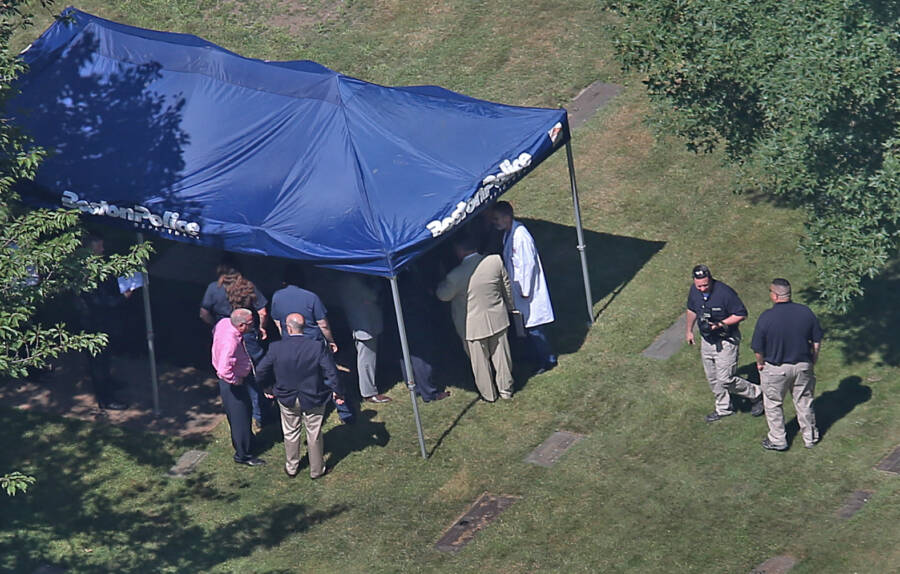

David L Ryan/The Boston Globe/Getty ImagesPolice exhume Albert DeSalvo’s body at the Puritan Lawn Memorial Park Cemetery in Peabody, Massachusetts, to compare his DNA to DNA found nearly 50 years prior at a Boston Strangler crime scene.

The Y-DNA, genetic material passed through the male line in families, found on the bottle was an almost exact match to semen found on a blanket that covered Sullivan’s body. After the Y-DNA match, police obtained permission to exhume Albert DeSalvo’s body and procure a DNA sample.

To their relief, it was a match. Authorities posthumously declared Albert DeSalvo the murderer of Mary Sullivan, closing her case.

But the cases of the 12 other Boston Strangler victims remain a mystery, as there was no DNA to match to on their cases. For that reason, the case of the Boston Strangler remains open to this day.

After reading about Albert DeSalvo, the self-confessed Boston Strangler, check out the story of Juana Barraza, who was a wrestler by day and murderer by night. Then, read how Ted Bundy helped authorities catch another serial killer, Gary Ridgway.