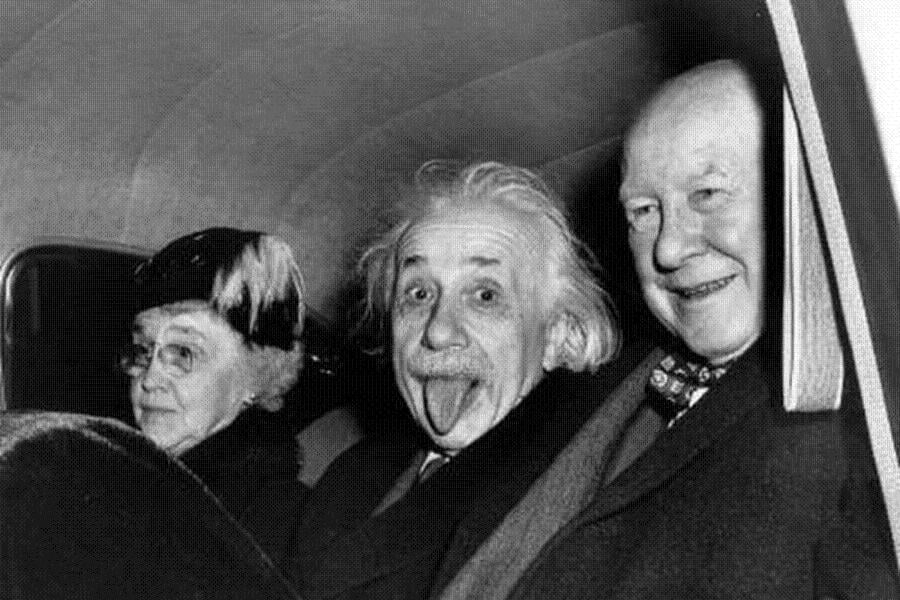

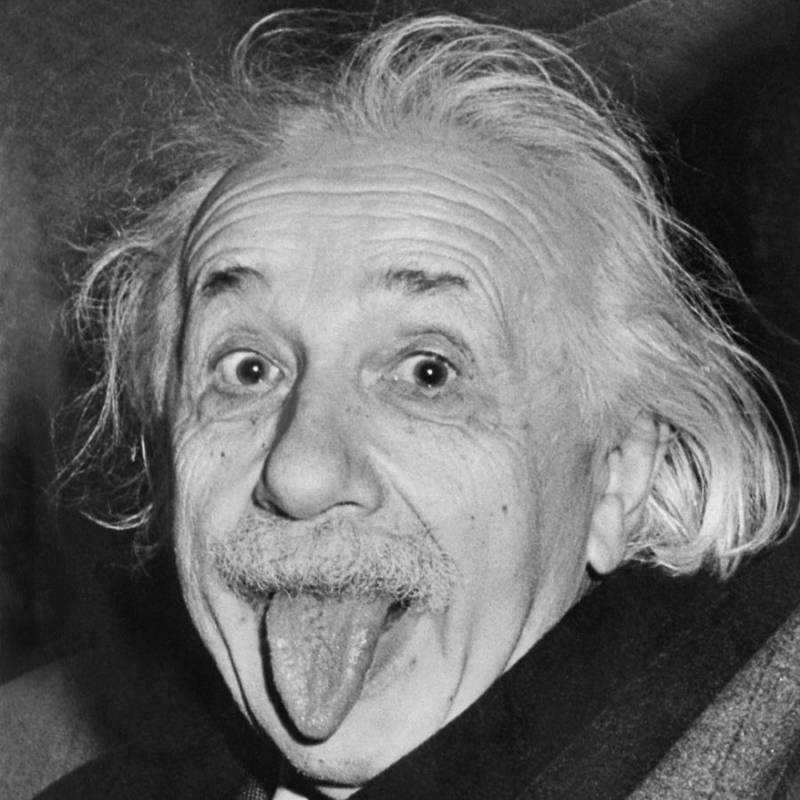

As it turns out, the iconic photo was nearly never published in the first place.

Arthur Sasse/AFP

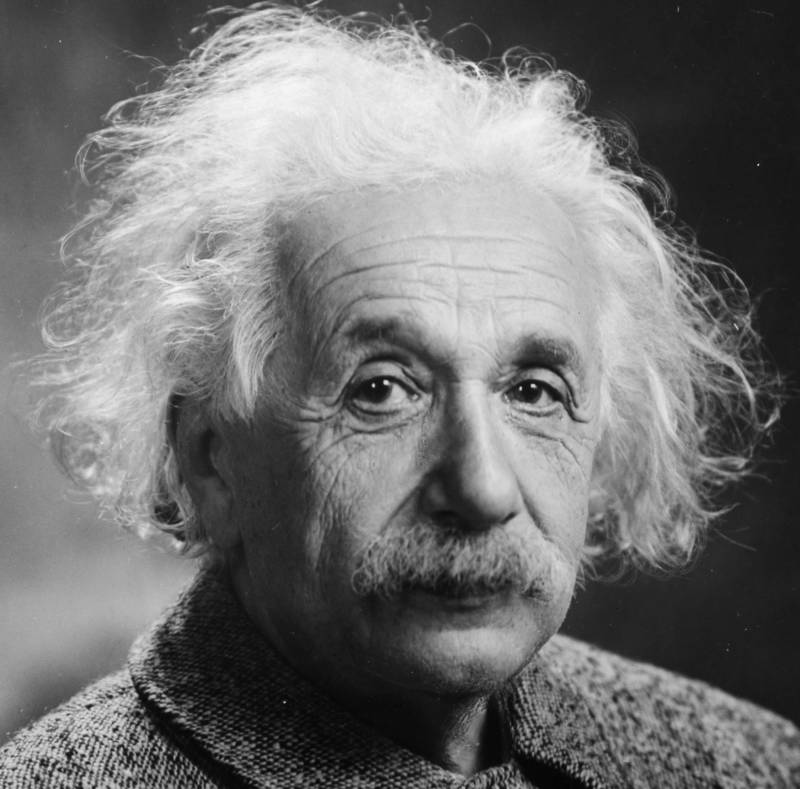

It’s the iconic image of Albert Einstein.

Sometimes it’s a wide-perspective shot that shows his companions in a car in the background. In other versions, it’s cropped to just show Einstein. Both versions capture the great physicist of the 20th century, white hair akimbo, sticking out his tongue in a moment of lighthearted fun before he heads home after a tiring night.

The photographer, Arthur Sasse, needed one last shot of the professor as he left, and what he got became a classic of the century’s photographic record.

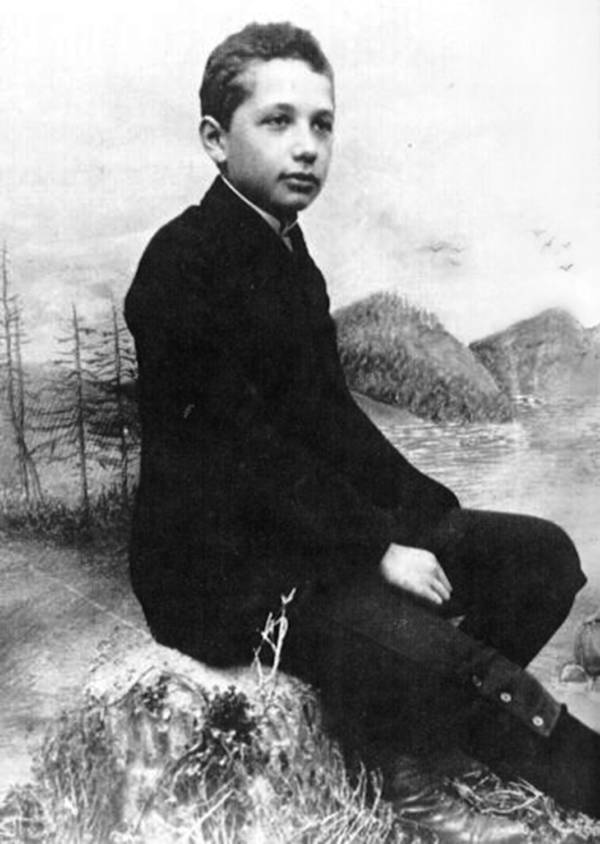

German Jews In Einstein’s Era

Wikimedia CommonsAlbert Einstein at age 14.

Had Albert Einstein been born a decade earlier, the world may not have ever known his name. Born in Germany in 1879, Einstein was part of the first fully free generation of European Jews since the 12th century.

Indeed, when the North German Confederation adopted a constitution that granted Jews civil rights in 1867, people took to the streets in protest.

For Einstein, born a little more than a decade later, life was different — though it had other challenges.

To his parents’ consternation, Einstein was slow to learn to talk. Contrary to popular anecdotes, Einstein was an average to above-average student who not only excelled at math, but planned to teach it when he graduated.

Those hopes were dashed, however, when he walked into a string of rejections at every university he applied to. Around 1900, the 21-year-old Einstein renounced his German citizenship and moved to Switzerland, where he supported himself and his wife as a freelance math tutor and “technical expert” at the patent office.

During his free time, he kept himself busy by drafting scientific papers that revolutionized physics forever.

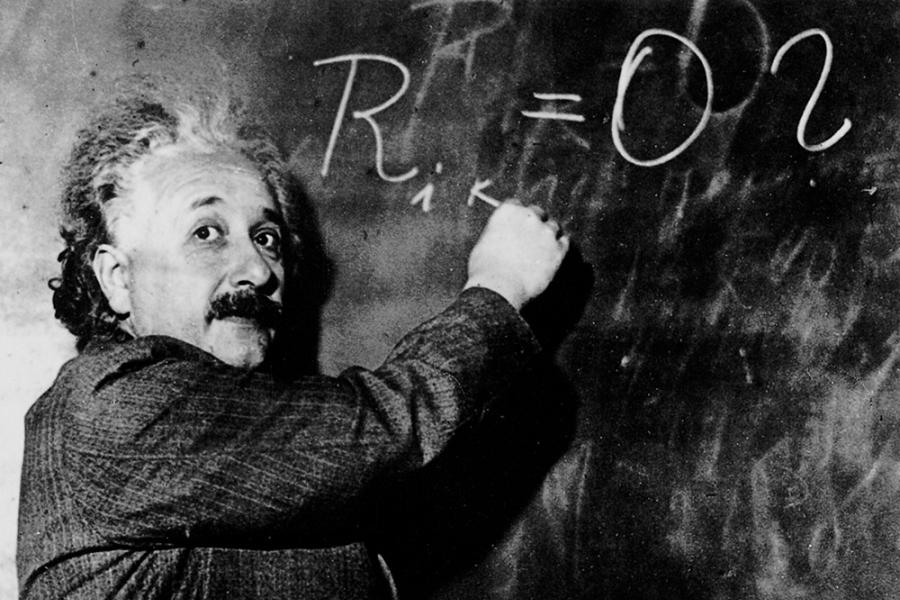

New Ideas In A New Home

Wikimedia Commons

In 1905, Albert Einstein authored several papers that utterly changed the way physicists thought about the world.

In the first, he theorized that light can only be emitted at discrete wavelengths. This would form the core of quantum mechanics, decades later. In another paper, he explained some of the strange things that electromagnetic force does with bodies in motion, making breakthroughs that are ultimately the reason we now have nuclear power. In yet another paper, “Does the Inertia of a Body Depend upon its Energy-Content?,” he first published the E=mc² equation that is all half of humanity knows about his contributions to science.

All of this output – some of which eventually won him the 1921 Nobel Prize – led to his acceptance at prestigious academic institutions until, in 1914, he was admitted to the Prussian Academy of Sciences and given a non-lecture position in Berlin. He worked there in relative obscurity throughout World War I, which seems to have made a committed pacifist out of him.

Fame and fortune came in 1919, when British physicists tested one of relativity theory’s predictions (about the deflection of starlight during an eclipse) and indeed found the effect Einstein had predicted. Almost overnight, English-speaking countries hailed Einstein as the next Isaac Newton, invited both Einstein and his wife on a series of lecture tours in Britain and America, where they were received as honored guests everywhere they went.

The good times came to a halt in 1932, when Germany held an election that left the Nazis as the largest single party in the Reichstag. In January 1933, President Hindenburg invited Chancellor Hitler to form a government. In March, Einstein resigned all of his German posts and asked for asylum in the United States. The next day’s headline in the Berliner Tageblatt read: “Good News From Einstein: He Isn’t Coming Back!”

The 54-year-old Nobel Laureate would never set foot in his native Germany again.

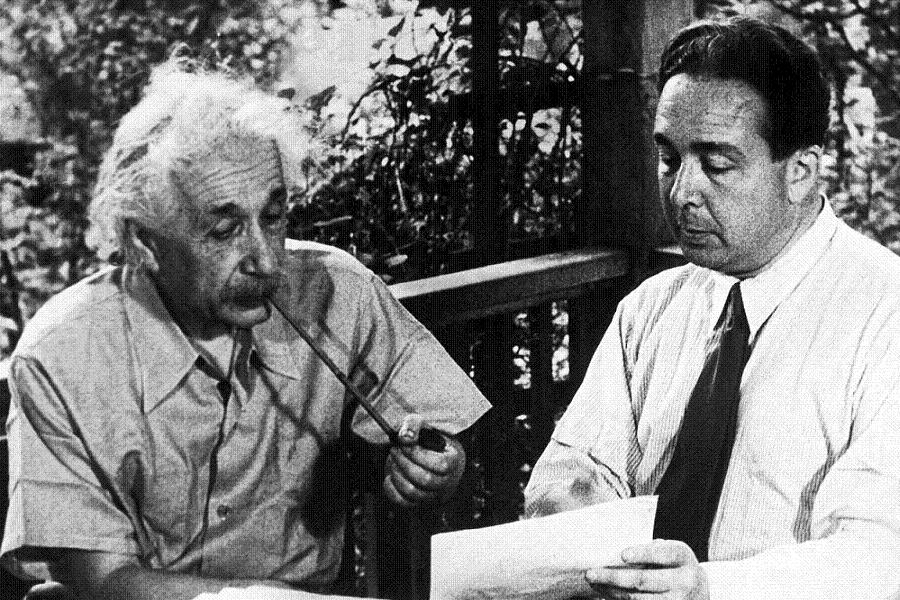

The Pacifist Who Devised A Weapon Of Mass Destruction

Wikimedia CommonsEinstein and Szilard after the war, recreating their collaboration on the infamous letter that sparked the Atomic Age.

Driving Albert Einstein away proved to be a bad decision for Germany.

No sooner had Einstein been granted permission to stay in the United States than the regents at Princeton met to discuss his application to teach at their Institute for Advanced Studies. The meeting wasn’t to consider whether or not to hire Einstein — that was a forgone conclusion — but only to work out his salary.

The board never reached a consensus and decided to let Einstein name a figure that would suit him. Einstein, in response, asked for $250 a month — about $50,000 a year in 2017 USD. Horrified, the university pressed him to accept a salary three times higher. Einstein agreed, and spent the last 22 years of his life at Princeton.

The same year Einstein was negotiating his salary at Princeton, another refugee from European dictatorship, Leo Szilard, was driving in London when he had an idea: What if an element could be found that emitted more neutrons when it split than it took to split it?

Comparing notes with Einstein later, the Hungarian scientist drafted a joint letter for President Roosevelt that described the potentially unlimited power of an atomic chain reaction. This letter sat doing nothing for a while, until 1942, when it inspired the Manhattan Project.

After the war, while Szilard became a strident supporter of ever bigger bombs in the US arsenal, Einstein repented from his role in developing the atomic bomb and worked for the last ten years of his life to put the genie back into the bottle that he and Szilard had rubbed.

The Nutty Professor

Wikimedia Commons

By the time the famous tongue photograph was taken, in 1951, things were a lot quieter for Einstein. He had spent the war years teaching at Princeton and generally basking in the adulation of a world that thought he was the greatest genius of all time.

Reveling in his image as the quintessential otherworldly scientist, Einstein deliberately cultivated eccentric mannerisms and habits. He rarely wore socks, for example, with the explanation that the big toe area just wore out quickly no matter what, and that shoes alone should do the job of holding a foot.

He also acquired an increasingly odd-looking wardrobe featuring bizarrely-patterned dressing gowns, and let his hair and mustache take over much of his head. When reached for interviews, he often gave them on his porch while wearing fluffy pink slippers. He was also quick with a joke for most visitors and seldom seen without his pipe, which he claimed aided in steady thinking.

It was this Einstein who attended his 72nd birthday party, which the staff at Princeton had thrown. There, he met professional photographer Arthur Sasse, who took several photos of Einstein as he shook hands and indulged in what for him was the rare glass of cognac.

As the party came to a close and a tired Einstein entered his chauffeured car, Sasse snuck up to the open door and called to him for one more photo. Einstein turned toward him and stuck out his tongue just as the flash went off.

Almost Not Published

Arthur Sasse/AFP

Arthur Sasse sent Einstein copies of all the photos that he had taken at the party. Einstein immediately fell in love with the last one in the gallery and ordered nine prints of it. He had many more made and included them in all of his greeting cards from then on.

After his death, four years later, Einstein’s estate licensed the image for wider circulation. Unlicensed reproductions spread even faster, and in the last 60 years, Einstein’s get-a-load-of-me portrait has appeared on mugs, T-shirts, posters, and probably every other surface that can be silk-screened.

Arthur Sasse submitted the photo for publication with the International News Photos Network, where it almost died on the editing table. Editors at the network debated the appropriateness of such a photo of an esteemed public figure like Professor Einstein, but decided to run it when they heard how much the subject himself enjoyed the image.

In time, the original print and negatives were auctioned for $72,300. To date, that makes “Einstein’s Tongue” the most expensive portrait ever taken of the old scientist, as well as one of the most iconic images of the century he did so much to influence.

After learning about the iconic Albert Einstein tongue photo, read up on the time that Einstein was offered the presidency of Israel, and check out some fascinating Albert Einstein facts that you’ve never heard before.