Anatoly Dyatlov was the Deputy Chief Engineer at Chernobyl on April 26, 1986, and was convicted for its catastrophic meltdown. But was he as reckless as the Soviet narrative claimed?

At 56, Anatoly Stepanovich Dyatlov was front and center in the worst nuclear disaster in world history. Anatoly Dyatlov was the Deputy Chief Engineer in charge of Chernobyl’s Reactor No. 4 when it exploded on April 26, 1986. The Soviet justice system subsequently blamed the horrifying incident on him and a few others.

According to The Washington Post, however, Dyatlov staunchly disagreed with this accusation. Nonetheless, he was found guilty of criminal negligence and received a 10-year prison sentence.

The Russians laid the blame squarely on Dyatlov, and he certainly was the highest-ranking engineer present at the site during the incident. But what happened, exactly, and what kind of man was Anatoly Dyatlov?

Let’s explore the man’s background, the decisions he made after the reactor’s explosion, and get to the core of what happened that night.

Welcome to Chernobyl.

April 26, 1986: Anatoly Dyatlov’s Fatal Test

The effects of the Chernobyl disaster surpassed the confines of Soviet Russia. Sweden detected notable amounts of radiation wafting from Asia to Europe just a few days after the reactor blew. The entire ecology of Pripyat, Ukraine was impacted, with both wildlife and humans in the region experiencing birth defects decades later.

The event occurred just as much out of negligence as an inevitability. With improper fail-safes to prevent radiation from escaping in case of an accident, improperly trained personnel, and no safety measures implemented to avoid those mistakes in the first place, the Chernobyl disaster was arguably waiting to happen.

ChernobylPlace.ComReactor 4 after the explosion. Late April 1986.

The world-famous catastrophe began with a seemingly innocuous late-night safety test. After the test went awry and human error compounded the problem, Reactor No. 4 became unmanageable. The core exploded, graphite was exposed to the open air, and thousands of radioactive particles escaped in plumes through the facility’s blown-out roof.

The two plant workers who died that night arguably suffered the least out of all those who died in the days and years after from radiation poisoning.

SHONE/GAMMA/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images The Chernobyl nuclear power plant a few months after the explosion on April 26, 1986.

Indeed, 134 of the servicemen who were involved in clean-up around Pripyat were hospitalized in the following days. Thirty-one people died as a direct result of the accident, including two workers, and an additional 29 firemen died as a result of acute radiation syndrome (ARS) in the following weeks. Fourteen more died of radiation-induced cancer within the next 10 years.

But how much of this was Anatoly Dyatlov’s fault, and how did he manage the situation in real time?

Anatoly Dyatlov Delegates At Chernobyl

Soviet authorities claimed that Dyatlov failed to follow the most basic safety precautions that night of April 26, 1986. Dyatlov was ordered by Moscow to perform an experiment that required he command his subordinates to engage in extremely risky and wholly unnecessary activities. The experiment in question was intended to confirm or deny whether the reactor could function under the electricity its own turbines generated once the power was cut off. If so, the reactor could remain in operation across unexpected power failures. While Soviet officials claimed Dyatlov didn’t take enough precautions, he vehemently disagreed with that point.

The narrative put forth by authorities insists that both Dyatlov’s bullying and bad decision-making, alongside avoidable mistakes made by his underlings, directly resulted in the reactor’s explosion. Five years after Dyatlov’s imprisonment, when he was freed through general amnesty issued to Chernobyl officials, he finally recounted his own version of events.

“I found myself confronted with a lie, a huge lie that was repeated over and over again by the leaders of our state and simple technicians alike,” he said of the story put forth by Soviet officials.

Jerzy KOSNIK/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesThe line at a pharmacy in Warsaw following the slow unfolding of information about Chernobyl. June 1986.

“These shameless lies shattered me. I don’t have the slightest doubt that the designers of the reactor figured out the real cause of the accident right away but then did everything to push the guilt onto the operators.”

Dyatlov himself received enough radiation that night to make him all but totally incapacitated. He could barely walk without tiring even a few years after the explosion. His memory, however, remained sharp. He claimed to have remembered every detail of that night, who did what, and why he wasn’t to blame.

Anatoly Dyatlov was in charge that night, so much of the responsibility for the reactor’s explosion had to rest with him. But the way he saw it, Soviet officials used him as a scapegoat instead of accepting their own culpability.

Igor Kostin/Sygma via Getty Images Few people know that there was a second Chernobyl explosion on Oct. 11, 1991, in the turbine hall of reactor two. The roof was blown off but there was no leak.

The first explosion, at 1:24 a.m., occurred when an unexpected surge of power produced an unsafe amount of steam pressure in Reactor No. 4. The Chernobyl plant opened up like a watermelon smashed on the ground. The explosion produced the equivalent of over 10 of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians were subsequently evacuated.

“If I had known then what I know now about what kind of monster this reactor was, I would never have gone to work at Chernobyl. And not only me. Nobody would have worked there.”

Indeed, the reactors at the Chernobyl plant were not even close to fool-proof. The Soviet-designed RBMK reactor, or Reactor Bolsho-Moshchnosty Kanalny meaning “high-power channel reactor,” was water-pressurized and intended to produce both plutonium and electric power and as such, used a rare combination of water coolant and graphite moderators that made them fairly unstable at low power. Thus, turning the machine off and cutting it from power for an “experiment” was an exercise in futility from the get-go.

What’s more, the RBMK design didn’t have a containment structure, which is exactly what it sounds like: a concrete and steel dome over the reactor itself meant to keep radiation inside the plant even if the reactor fails, leaks, or explodes.

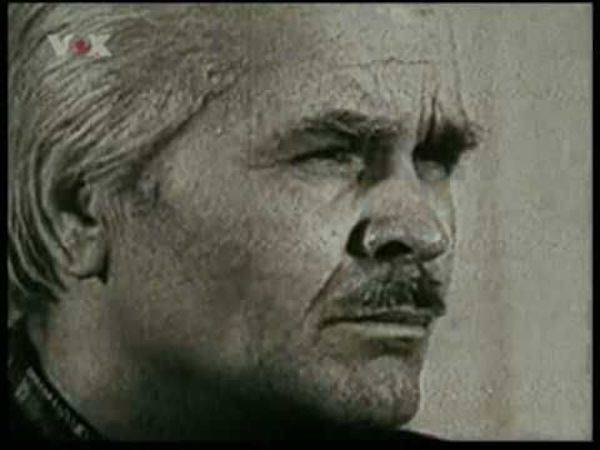

VOXDyatlov received a heavy dose of radiation on the night of the reactor’s explosion. He died at 64 years old.

Unlike the official version of events claimed, Dyatlov said the control room atmosphere was stable until the moment the reactor exploded. Not a single person present that night observed anything unusual until then, he said. Dyatlov even thought that it was merely a gas tank which blew up on the building’s roof when the failures in the reactor began. After all, plaster and dust crashed onto the machines in the control room. “Everyone to the reserve switchboard,” he ordered.

But when the computers indicated that steam in the reactor wasn’t turning the turbines anymore and that cool water was no longer being pumped into the reactor to keep it at a stable temperature, Dyatlov began to panic.

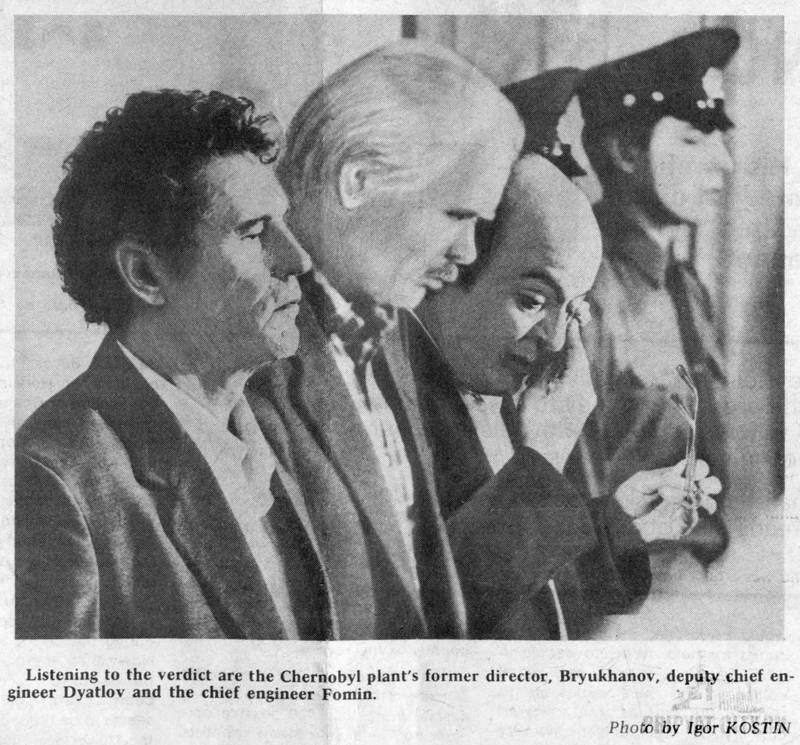

Igor KostinChernobyl plant director Viktor Bryukhanov, Anatoly Dyatlov, and chief engineer Nikolai Fomin listen to the verdict at their 1987 trial following the disaster.

Ultimately though, it was confirmation that the power in the reactor was increasing, rather than decreasing, which truly terrified Dyatlov.

“I thought my eyes were coming out of my sockets,” he said. “There was no way to explain it. It was clear that this was not a normal accident, but something much more terrible. It was a catastrophe.”

Unfortunately, the poor design of the RBMK reactors only made matters that much worse. To control the nuclear radiation, dozens of neutron-absorbing rods had to be lowered directly into the core of the reactor. The rods, however, were designed in such a manner that the absorbent elements were in the middle.

Once the tip of those rods was inserted into the core, they displaced water and subsequently created enough power to trigger an explosion. While Dyatlov may not have been entirely forthcoming with his own recounting of events, one thing is considerably plausible: why would he, or anyone else at the scene, have known that the device to prevent an explosion would trigger one? And if he did know — why would he have purposefully done so?

Igor Kostin/Sygma/Getty ImagesAnatoly Dyatlov was sentenced to 10 years in prison of which he served only five as he received amnesty.

“When they ran out into the corridor, I realized it was a stupid thing to do,” he said in reference to ordering operators to manually lower the rods. “If the rods had not come down by electricity or gravity, there would be no way of getting them down manually. I rushed after them, but they had disappeared.”

Those two operators, Viktor Proskuryakov and Aleksandr Kudyavtsev, both died terribly after being in such close contact with the exposed reactor. After they ran off, Dyatlov headed to the turbine hall to have a look for himself. What he saw were flames, a destroyed roof, water spilling onto machinery, and short circuits producing continuous clicking sounds. More disturbing still, the two operators were lying dead and covered in a grimy brown nuclear wash.

It was 4 a.m. when Dyatlov grabbed computer printouts and delivered them to Viktor Bryukhanov, the plant’s director. Bryukhanov told Moscow that the reactor was still intact, when it had actually blown to pieces and released a graphite fire onto the roof and lawn of the building.

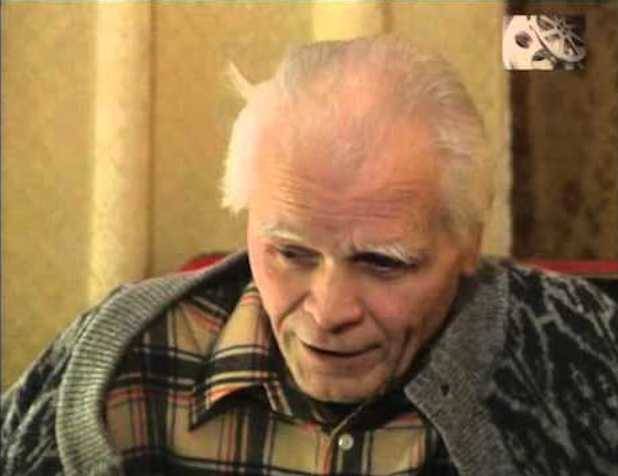

KruchinaFILMDyatlov died in Kiev on Dec. 13, 1995. He was 64 years old.

“I don’t know how he reached that conclusion,” said Dyatlov. “He did not ask me if the reactor was destroyed — and I felt too nauseated to say anything. There was nothing left of my insides by that time.”

To his point, there really was nothing left for Dyatlov to do. Professional firefighters from Chernobyl and Pripyat were called, and 27 of them were sent to the hospital that night. Their courage and determination helped to get the fire under control by dawn, but nobody was wearing protective clothing that night and the only dosimeters available couldn’t even provide an accurate read of the radiation leaking out.

The fire was eventually managed, but months of hard work by physicists, engineers, and laborers lay ahead. The compartmentalization of blame and Soviet bureaucracy, too, had only just begun.

Frankly, that aspect of this catastrophe has never been more patiently explored than by HBO in its 2019 mini-series, Chernobyl.

Chernobyl: A Nauseating Piece Of Entertainment

“What happened after Chernobyl was what always happens in these cases,” said Dyatlov, whose fictional version is portrayed by actor Paul Ritter. “The investigation was carried out by the very people who were responsible for the faulty design of the reactor. If they had admitted that the reactor had been the cause of the accident,” Dyatlov mused, “then the West would have demanded the closing down of all other reactors of the same type. That would have dealt a blow to the whole of Soviet industry.”

HBOPaul Ritter portrays Anatoly Dyatlov in HBO’s Chernobyl. Both character and real-life counterpart seemed to have no idea what was at stake until it was too late.

Writer and producer Craig Mazin certainly conveyed the hypocrisy of Soviet officials passing the blame on to each other while pretending to be interested in solutions effectively. Fortunately, any artistic liberties taken by Chernobyl seem to be minor alterations of facts in order to fit the truth into a six-hour series.

According to Business Insider, the show is largely accurate. Many of the debatable aspects are simply too difficult to discern fully from the facts, explained Mazin. In the real-life Chernobyl incident, “a lot of radioactive material was brought into the atmosphere,” and was “spread over a very large area.” The full disaster, then, is difficult to quantify.

The notion that Chernobyl gave off nearly twice the amount of radiation as Hiroshima every hour, is simply too difficult to confirm or deny. In Hiroshima, he said, the health impacts stemmed from direct contact with radiation. Since Chernobyl’s impact crossed continents, they matters are too incongruous to truly compare.

The portrayal of Soviet squads ordered to shoot animals in the Chernobyl exclusion zone, however, is accurate. When Pripyat’s residents were given 50 minutes to grab their belongings and board the evacuation buses — pets were not allowed.

While 300 stray dogs today wander the area known now as Chernobyl’s radioactive Red Forest, Soviet squads were indeed commanded to kill any roaming animals on sight after the city was first evacuated.

Ultimately, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster was a wake-up call to the entire world. Human technologic achievement had reached the point of being able to harness the power of the sun. As a result, any one nation’s meddling with this responsibility wasn’t just their own business anymore as the whole world could be implicated in disaster under the wrong circumstances.

Strangely enough, no piece of film or television work has ever come as close to depicting the harrowing event in full until now. With the right kind of cinematography, patient editing, and bleak depiction of what happened that year — a whole new generation might get a healthy dose of what we’re dealing with to this day in the fallout of the Chernobyl disaster.

As for the real-life Anatoly Dyatlov, the man died on Dec. 13, 1995, a couple of years after publicly explaining himself in an interview with The Washington Post. While some may consider him the true villain of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, the decades-long passage of time seems to indicate that other, more negligent forces were at play that day, as well.

After learning about Chernobyl engineer Anatoly Dyatlov, take a look at these 37 photos of the town of Chernobyl frozen in time today. Then, learn about Stanislav Petrov: the man who single-handedly prevented nuclear armageddon.