Researchers uncovered the infamous parasite Giardia duodenalis in cesspits beneath the ancient latrines.

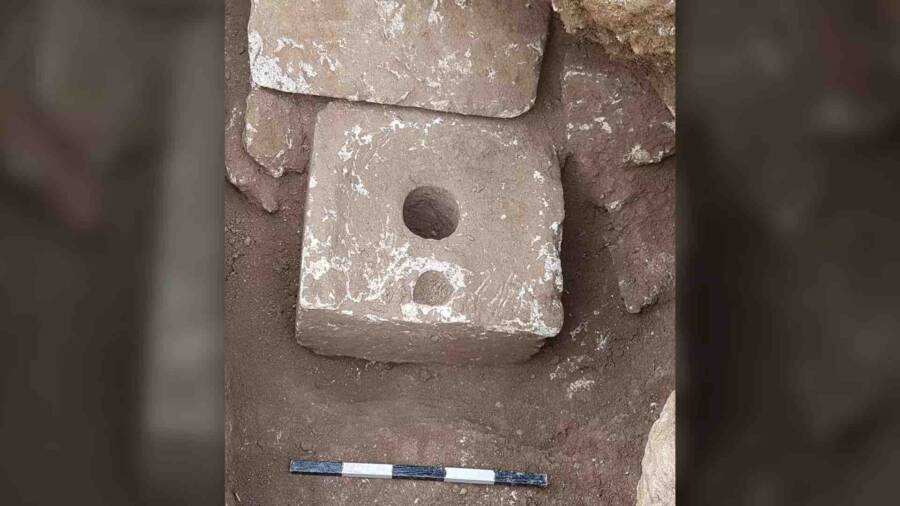

Ya’akov BilligThe cesspits were found beneath ancient stone toilets in Jerusalem, which likely belonged to Iron Age elites.

Poop samples from two ancient toilets in Jerusalem revealed the earliest known evidence of a parasite that causes “traveler’s diarrhea,” according to a new study. The poop in question is 2,500 years old.

The infection, also known as dysentery, is often caused by a microscopic parasite called Giardia duodenalis. The end result is horribly bloody diarrhea, often accompanied by abdominal cramps and a fever.

The discovery was made by a team of researchers from the University of Cambridge, Tel Aviv University, and the Israel Antiquities Authority as part of an ongoing excavation of cesspits beneath stone toilets that would have once been inside households reserved for Assyrian elites.

The new research, published in the journal Parasitology, declares the recent find the earliest-known evidence of G. duodenalis in human feces.

The cesspits were originally found beneath two large sites that likely served as homes for elites between the seventh and sixth centuries B.C.E. During this time, there were large stone blocks that were specially carved to be used as toilets. They had a curved surface where one could sit, and two holes that led down to the cesspits. The larger one, researchers believe, was used for defecating, and the smaller one may have been used for urination.

But these toilets were from a time long before sewerage systems, researchers noted: “Towns were not planned and built with a sewerage network, flushing toilets had yet to be invented, and the population had no understanding of existence of microorganisms and how they can be spread.”

Because of this, anything that was disposed of into the cesspits has remained there ever since. Previously, researchers have found whipworm, roundworm, pinworm, and tapeworm eggs in the cesspits, indicating that sanitation was a major issue for even the elites in Iron Age society.

They also uncovered ancient human feces in the sediment, which provided a unique opportunity for specialists to find the dysentery parasite. Microorganisms that cause dysentery are typically difficult to detect, but researchers believed that they could identify them in the stool using a technique called ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay), which can detect the antigens made by a variety of different organisms.

F. VukosavovićThe team analyzed multiple samples of feces and found microorganisms that could cause dysentery.

They took a single feces sample from the cesspit at the House of Ahiel, just outside Jerusalem, and three samples from the cesspit at Armon ha-Natziv, which is about one mile south, and used ELISA kits to examine the samples, testing for Entamoeba, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium — all of which are among the most common causes for outbreaks of dysentery.

While tests for Entamoeba and Cryptosporidium were negative, experts found positive results when testing for antigens created by Giardia.

The antigen was a cyst wall protein released by G. duodenalis, a pear-shaped parasite that spreads through food and beverages that have been contaminated by the feces of an infected person or animal. Ancient cities like Jerusalem would have been hotbeds for this type of infection to spread, especially by traders or traveling soldiers, the study noted.

Although a person infected with G. duodenalis typically recovers quickly, the parasite does cause disruptions to the person’s gut lining. As a result, other harmful microorganisms can enter the gut, which can lead to worse illness.

“We cannot tell the number of people infected based on sediment samples from communal latrines,” study lead author Piers Mitchell, a paleo-parasite research specialist, told Live Science. “It is possible the toilets may have been used by family and staff, but that is merely a possibility, as no records survive describing that sort of social etiquette.”

Other examples of G. duodenalis had previously been identified across ancient history, including in Roman-era Turkey and medieval Israel, but this discovery marks the oldest known identifiable occurrence of it.

It makes sense, too, that the disease would be widespread throughout ancient regions of the Middle East. It was the first area where humans established long-term settlements, domesticated animals, and constructed massive cities where large groups of people congregated together.

With such a high population of both people and animals, and poor sanitation practices, disease spread quickly and easily with no real way to combat it.

As researchers noted in the study, more research with ELISAs into how G. duodenalis spread throughout ancient societies could one day help identify where the microorganism first originated.

After learning about these ancient toilets and the secrets that lay beneath them, read about the man who damaged the oldest toilet in Japan by backing into it with his car. Or, read about another strange parasite — one that lives inside the eyeballs of fish to control their behavior.