Experience photos and stories from inside Georgia's Andersonville Prison, one of the most brutal prisoner of war camps in modern history.

Andersonville Prison was never meant to hold as many prisoners as it did.

During the first years of the Civil War, Confederate soldiers had been toting their Union POWs around with them or dropping them in makeshift camps around the Confederacy.

By the last year of the war, however, they’d realized they needed a more secure solution.

Constructing Andersonville Prison

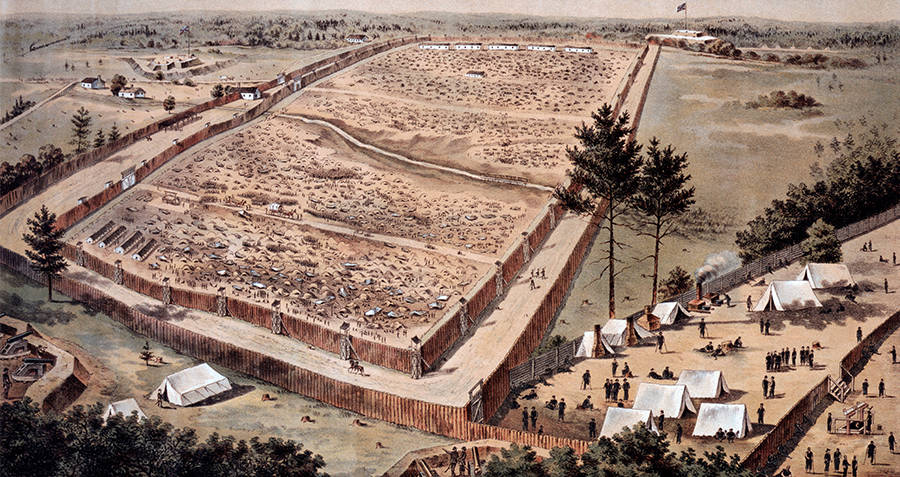

Getty ImagesAndersonville Prison

Camp Sumter, later known as Andersonville Prison, was that solution. Built to be roughly 1,620 feet long and 779 feet wide in rural Georgia, the camp was expected to accommodate about 10,000 men and had been outfitted with the bare minimum of accommodations to do so.

Within a year though, the camp was home to four times that amount, and conditions declined rapidly. Not only was the camp struggling for resources like clothing and space, but the prisoners were at risk of death from disease, starvation, and exposure.

Before long, Andersonville Prison had become the worst prisoner of war camp that the United States had ever seen.

As soon as the first prisoners arrived, they could tell that the conditions would be unforgiving.

The camp was surrounded by a 15-foot-high stockade, but the real danger was the line that lay 19 feet inside that stockade. Known as “the dead line,” the line marked the entrance to a no-mans-land, a strip of land that kept the prisoners away from the stockade walls.

Dotted around the dead line were towers known as pigeon roosts, in which Confederate soldiers kept watch. Anyone crossing, or even touching, the dead line was allowed to be shot and killed without warning by the soldiers in the roosts.

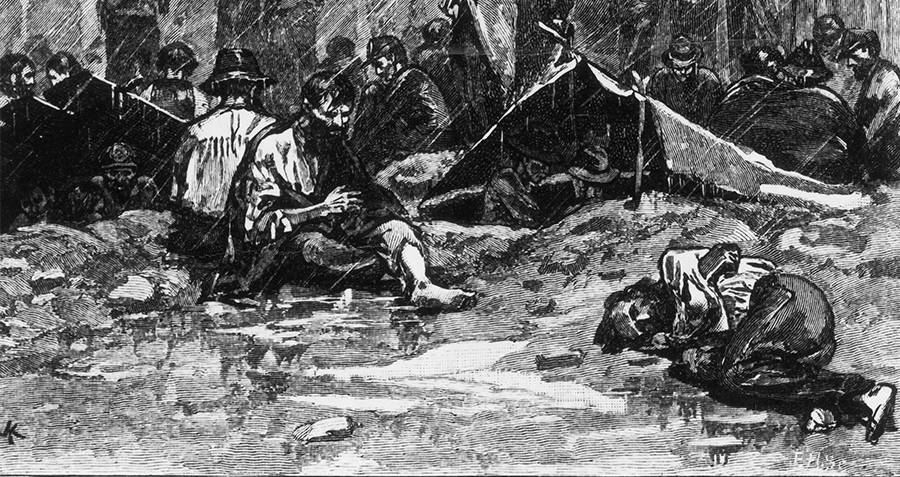

Getty ImagesInmates brave the harsh conditions of Andersonville Prison.

It may seem unnecessary to keep guards posted around the dead line, because who would ever consider crossing it when the penalty was so severe? But, lo and behold, some prisoners did cross it, for the conditions they faced inside the line were far worse than the prospect of death outside it.

As for the conditions inside, the largest problem that the prison had was first and foremost the overcrowding. Because the expected number of prisoners had been so low when construction began, the camp had simply not been built to accommodate the nearly 45,000 prisoners it held by 1865.

Aside from a sheer lack of space, the overcrowding caused a host of other problems, ranging from things like a lack of food and water (the leading cause of death among the prisoners was starvation) as well as clothing to severe issues like disease outbreaks.

“Can This Be Hell?”

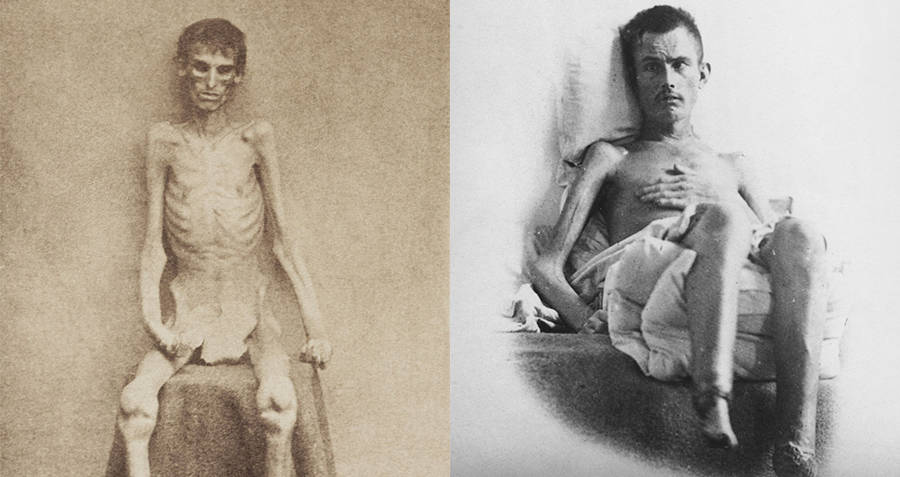

Andersonville Prison was frequently undersupplied with food and fresh water, as the Confederacy placed a higher priority on feeding their soldiers than their prisoners. Emaciated, the prisoners then wasted away.

Those who didn’t die from starvation often contracted scurvy from vitamin deficiencies. Those who didn’t contract scurvy were often subjected to dysentery, hookworms, or typhoid from the contaminated water at the camp.

Those who managed to scrape by, surviving starvation or poisoning from the water were likely to die from exposure, as the overcrowding and arrival of at least 400 new prisoners a day forced the weakest out of the tents and into the open.

“As we entered the place, a spectacle met our eyes that almost froze our blood with horror, and made our hearts fail within us,” wrote prisoner Robert H. Kellogg, who entered the camp on May 2, 1864. “Before us were forms that had once been active and erect;—stalwart men, now nothing but mere walking skeletons, covered with filth and vermin. Many of our men, in the heat and intensity of their feeling, exclaimed with earnestness: ‘Can this be hell?’ ‘God protect us!'”

Emaciated former inmates who survived Andersonville Prison.

Six months in, the creek banks had eroded, making way for a swamp that occupied the large central portion of the camp.

“In the center of the whole was a swamp, occupying about three or four acres of the narrowed limits, and a part of this marshy place had been used by the prisoners as a sink, and excrement covered the ground, the scent arising from which was suffocating,” wrote Kellogg. “The ground allotted to our ninety was near the edge of this plague-spot, and how we were to live through the warm summer weather in the midst of such fearful surroundings, was more than we cared to think of just then.”

If the horrifying conditions inside the camp weren’t bad enough, the treatment the prisoners received at the hands of the guards may have topped it. Guards regularly brutalized the inmates, especially those who couldn’t fight back or fend for themselves.

Eventually, one of the commanders was executed for his crimes following the war after prisoners and even a few other guards testified that he had tortured inmates, allowed other guards to torment them, and turned a blind eye to mistreatment.

Prisoners Left To Their Own

In response to the harsh conditions and the guards’ treatment, the prisoners were forced to fend for themselves.

As a result, a sort of primitive social network and hierarchy arose. Those prisoners who had friends, or at least men willing to watch out for them, tended to survive much longer than those on their own. Each group shared the rations of food, clothes, shelter, and moral support, and would defend each other from other groups or guards.

Eventually, Andersonville Prison formed its own sort of judicial system, with a small jury of inmates and a judge who kept a reasonable amount of peace. This came in handy when one group took survival too far.

Known as the Andersonville Raiders, this group of prisoners would attack fellow inmates, stealing food and wares from their shelters. They armed themselves with crude clubs and bits of wood, and were prepared to fight to the death should the need arise.

Wikimedia CommonsThe makeshift tents in which inmates lived at Andersonville Prison.

An opposing group, calling themselves the “Regulators,” rounded up the Raiders and put them before their makeshift judge. The jury then sentenced them to whatever punishments they could, including running the gauntlet, being sent to the stocks, and even death by hanging.

At one point, a Confederate captain even paroled several Union soldiers, ordering them to take a message back to the Union asking to reinstate prisoner exchanges. Had the request been accepted, the overcrowding could have stopped, and the prison could be rebuilt into a more acceptable prison camp.

The request, however, was denied, along with several subsequent ones.

The Liberation Of Andersonville Prison

Finally in May of 1865, following the end of the Civil War, Andersonville Prison was liberated. Several military tribunals were conducted in order to hold the captains responsible for their war crimes. Through scattered research, the Union army discovered that 315 prisoners had managed to escape Andersonville, though all but 32 were eventually recaptured.

They also found a list, handwritten by a young Union soldier, of all the prisoners kept in Andersonville. It was published in the New York Tribune upon the end of the war and used to create a monument at the site of Andersonville Prison to all of the men who had suffered inside of its walls.

Today, the site is a national historic site that serves as a reminder of the horrors that occurred there some 150 years ago.

After learning about the horrors of Andersonville Prison, see some of the most haunting Civil War photos. Then, read up on the worst war crimes ever committed.