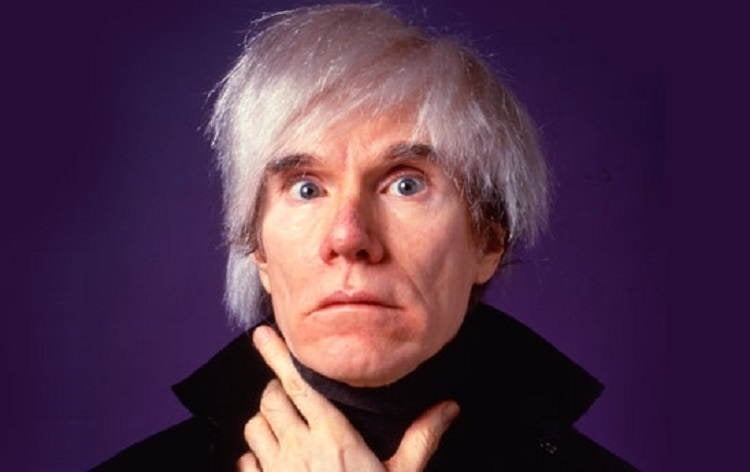

While Andy Warhol is best known for turning the mundane into art, his death revealed to fans a debilitating part of his life: hoarding.

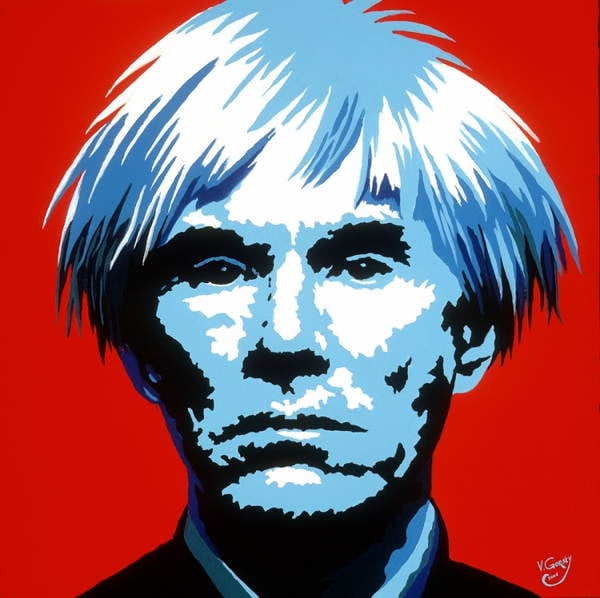

Long before YouTube, Facebook or even MTV’s genre-spawning “Real World,” when Andy Warhol coined his now-prescient phrase “fifteen minutes of fame,” he believed that technology and culture would merge to deliver everyone a moment of personal superstardom.

But he couldn’t have known that some people would earn their notoriety by exposing the misery and sickness of living in chaotic clutter.

Source: Traffic Magazine

Nevertheless, it’s doubtful Andy would have been shocked by a TV show like today’s “Hoarders.”

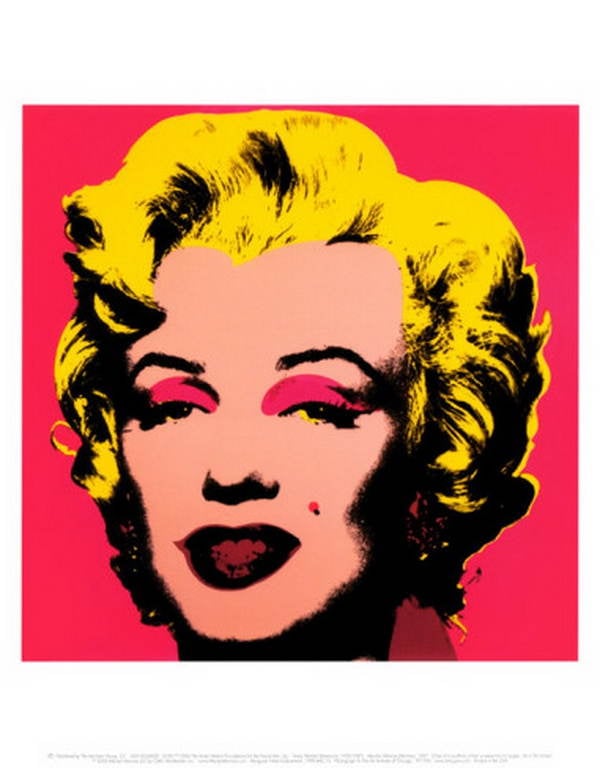

In his own life, Warhol also seemed to blur the line between collecting and compulsive squirreling away. The man who multiplied Marilyns, Judys and English Monarchs for public consumption through New York Factory-made silkscreens, amassed a mountain of what he simply called “stuff” in his own four-story East Side townhouse and nearby storage.

In stark contrast to the chaotic atmosphere in Warhol’s famed Factory, where he often created artwork while members of his drug-addled entourage of drag queens, drifters and other hangers-on watched, the front parlors of Andy’s home were comparatively tidy and tastefully decorated. But behind those walls, other rooms were packed to capacity.

The public learned the extent of Warhol’s hoarding habits after he died in 1987, leaving behind urban digs that were a world unto themselves, filled with disparate collections of airplane menus, unpaid invoices, pizza dough, pornographic pulp novels, grocery store fliers and stamps. Warhol had 600 boxes filled with used plane tickets, souvenirs, newspapers and other ephemera that he had been collecting since 1973.

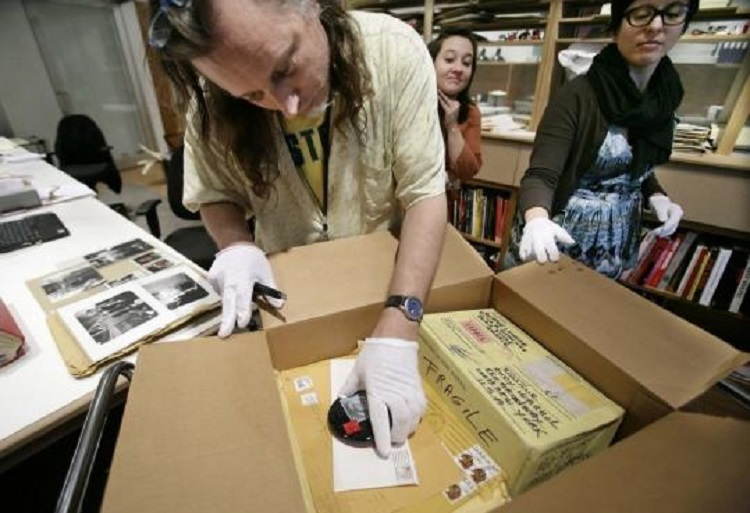

Warhol called them cardboard “Time Capsules”, seeing the boxes more as an artistic pursuit than he did signs of potential illness. The boxes are now housed at the Andy Warhol Museum in the artist’s hometown, Pittsburgh, where their contents are periodically put on display.

Source: Boston Globe

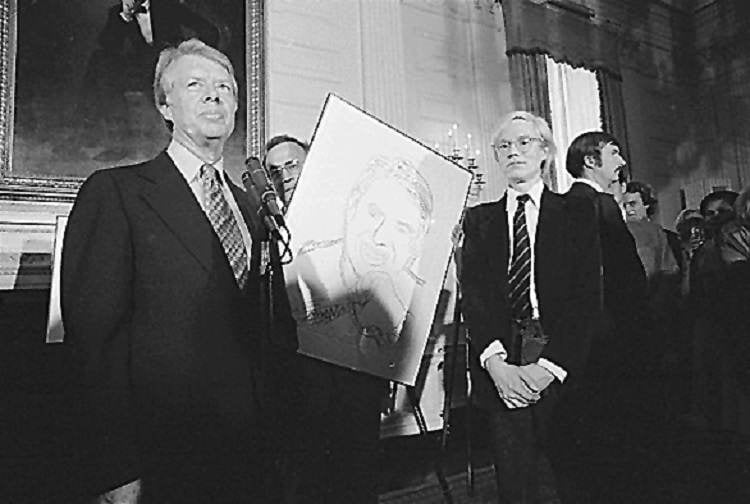

But Warhol, probably best remembered for turning a Campbell’s soup can into art, left behind instructions for other flotsam and jetsam to be sold and raise money for the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, which would serve as the pop artist’s estate and funding source for emerging artists.

Incredibly, it took a year for Sotheby’s auction house in New York to research and catalog everything—artwork, clothing, precious gems, decor, even Warhol’s 1974 Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow and a mummified human foot from Ancient Egypt that he might have found at a flea market.

Source: Sky Mag

With obvious appeal to other collectors (or hoarders, as the case may be), the auctioned items also included high-end examples of Federal-era furnishings, Art Deco furniture and silver, important postwar art and American Indian artifacts in what was billed “one of the largest and most diversified holdings ever auctioned at Sotheby’s.”

Source: WordPress

By the numbers: items included 313 watches, 57 Navajo blankets, 210 Bakelite bracelets, 1,659 pieces of Russel Wright pottery and 170 chairs. But the pièce de résistance focused on by the press was a collection of 175 kitschy cookie jars in the shape of dogs, pigs, houses and pandas.

They alone sold for nearly a quarter-million dollars, mostly to one bidder. A particularly coveted grouping fetched $23,100, breaking the record at the time for a lot of cookie jars sold at auction.

Andy Warhol’s townhouse. Source: Sotheby’s

More than 10,000 items in 2,526 lots went on display to the curious public before the auction, causing people to line up to see and perhaps acquire a little piece of Andy. According to Sotheby’s website, the auction house hoped to hit $15 million in proceeds; the sale raised $25 million.

The Andy Warhol Museum was able to reunite about 300 of the items for an exhibition in 2002 and the world may continue to see signs of Andy’s hoarding for years to come. Last year, The New York Times published a lugubrious story about another New York artist, photographer Harry Shunk, whose work created with his partner János Kender, is part of the Metropolitan Museum’s permanent collection.

Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

After splitting with Kender in the 1970s, Shunk became a recluse and spent the rest of his life in his West Village apartment that he stuffed with various objects for many decades. When he died in 2006, more than a week had elapsed before his decomposing body was discovered upside down and trapped by stacks of his possessions.

Salvage efforts were hampered by the sheer mass accumulated inside. Workers had to remove the door in order to get inside, and anything deemed valuable was taken to be sold. A cleanup guy named Darryl Kelly was hired to get the rest of the apartment back in shape. Most of it went into a dumpster.

Darryl Kelly with one of his discoveries.

Kelly told the Times that items were “piled to within a foot of the ceiling. I had to send a skinny man in there to climb up over it to the window.”

After finishing their work, Kelly and his brother-in-law Gregory Marsh made a last-minute decision to grab a few things out of the trash when they saw other people going through it. What he pulled out of the detritus languished in a SoHo storage locker for several years before Kelly got curious about what he might have.

When Kelly finally had the items examined by an art professional in 2012, the former rubbish was deemed to be worth a small fortune. Among three-dimensional maquettes by Christo, photographs of artist Yves Klein and prints by Paul Jenkins were some pieces by Andy Warhol, including a lithograph of Marilyn Monroe in hot fuchsia.

Today, Warhol’s images are among the most expensive artworks ever sold, with one commanding $105 million last year. The cleanup man is now set for life, all because he hoarded his collection for years, not knowing what sort of treasure trove he had.

Next, read some of the most fascinating stories about Andy Warhol.