The first African American fashion designer to open a store on Madison Avenue, Ann Lowe was known as "society's best-kept secret" in New York.

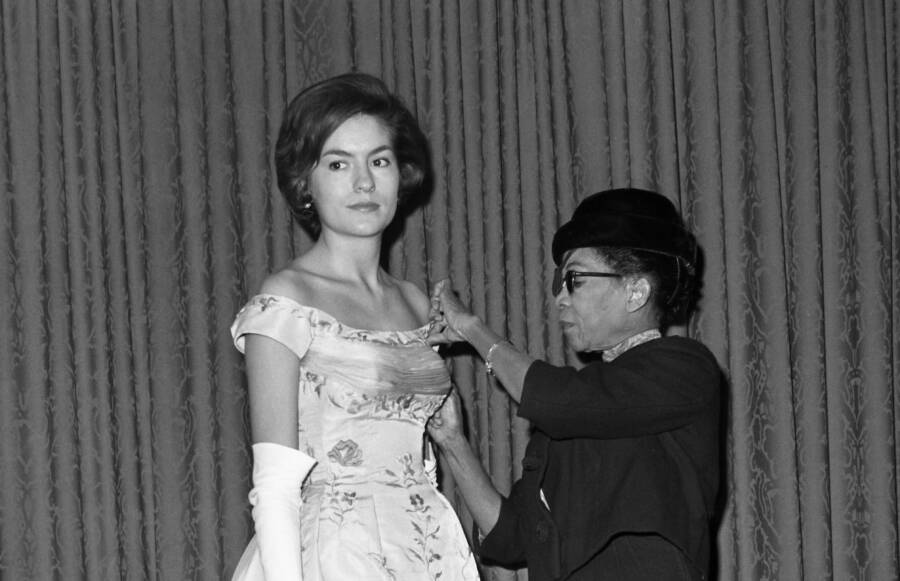

Bettmann Archive/Getty Images Ann Lowe at work in 1962.

On Sept. 12, 1953, Jacqueline Lee Bouvier floated down the aisle in a cloud of ivory-colored taffeta and tiny wax flowers toward her husband-to-be, John F. Kennedy. Her stunning wedding gown drew worldwide approval. But the woman behind the dress, a Black fashion designer named Ann Lowe, lingered uncredited in the shadows.

But Ann Lowe was more than a fashion designer. She was the fashion designer for New York’s upper crust. Lowe even described herself as “an awful snob” who didn’t make dresses for just anybody.

Still, Lowe rarely got her due. Even Jacqueline Kennedy dismissed her wedding dress designer as “a colored woman dressmaker” to the press. But in recent years, Ann Lowe’s beautiful dresses are getting a well-deserved second look.

Ann Lowe’s Inherited Talent

Ann Lowe was born in Clayton, Alabama in 1898 to a family with an eye for beauty. Her grandmother, born into slavery, designed dresses for her mistress. And Lowe’s mother had a talent for embroidery.

National Museum Of African American History And CultureA silk satin cropped jacket and dress designed by Ann Lowe in the 1950s.

“[Lowe] learned from them,” said National Museum of American History Curator Emeritus Nancy Davis. “She was really gifted, but she was also part of this lineage of seamstresses… and really capable ones.”

The three women started a successful dress company in Montgomery, Alabama. But tragedy struck the family in 1914 when Lowe’s mother died. Lowe, just 16, picked up her mother’s work. As she produced designs for high-end clients like the First Lady of Alabama, word of her talent spread.

“All the pleasure I have had, I owe to my sewing,” Lowe later declared. Her passion drove her work, and her work drove her to New York City, where she enrolled at S.T. Taylor Design School in 1917.

Because she was the only Black student, Lowe was segregated from the others. She studied in a room by herself. But Lowe’s work was so extraordinary that instructors constantly held it up as an example to others.

Upon her graduation, she opened up Ann Lowe’s Gowns in Harlem. And soon, Lowe was making dresses for New York’s upper echelon — the Roosevelts, the Rockefellers, and the du Ponts.

“I love my clothes and I’m particular about who wears them,” Lowe said later. “I sew for the families of the Social Register.”

One of her clients was the Auchincloss family, whose youngest daughter, Jacqueline, was about to marry.

Jackie Kennedy’s Wedding Dress

To create the perfect wedding dress, Janet Lee Auchincloss, Jacqueline Bouvier’s mother, enlisted Ann Lowe.

Bachrach/Getty ImagesJacqueline Kennedy wearing Ann Lowe’s wedding dress on September 12, 1953.

According to Lowe biographer Julia Faye Smith, Janet wanted her daughter to have a “large, elegant fabric, a fairy tale dress.”

Even the groom’s father weighed in. Joseph Kennedy, with an eye on his son’s political future, wanted something spectacular.

So Lowe got to work. She and her assistants labored for months, perfecting the intricate folds of the gown with more than 50 yards of silk taffeta.

But then the unthinkable happened. Lowe’s studio flooded. Not only was the wedding dress destroyed, but so were all of the bridesmaids’ dresses.

Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesJacqueline Kennedy throws her bouquet from the stairs wearing Lowe’s gown. September 12, 1953.

Lowe had just ten days to recreate the entire array — and she did, at a loss, without ever informing the families of what had happened.

The Kennedy wedding went off without a hitch. Everyone adored Ann Lowe’s wedding dress — except for the bride.

“[Jackie] didn’t love the dress, and people asked her who did the dress,” explained Rosemary E. Reed Miller, the author of Time, The Fabric of History: Profiles of African American Dressmakers and Designers from 1850 to Present.

“She said, ‘I wanted to go to France, but a colored dressmaker did it.’ “And Ann Lowe was devastated.”

Ann Lowe’s Designs Today

The years following the Kennedy wedding were difficult for Lowe. Her son, who’d helped run her dressmaking business, died in a car crash in 1958.

National Museum Of African American History And CultureOne of Ann Lowe’s dresses featuring swirls of handmade fabric rose vines crafted from silk, tulle, and linen. 1966-1967.

“Too late, I realized that dresses I sold for $300 were costing me $450,” Lowe said. She declared bankruptcy — but an anonymous benefactor stepped in and paid her debt. Many believe it was Jacqueline Kennedy.

But eventually, Lowe’s opulent designs fell out of fashion. Lowe herself died in 1981 at the age of 82, her contributions to American history and fashion overlooked or ignored the mainstream industry.

But Lowe was never forgotten. Her dresses are part of the permanent collection at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened in 2016, and were included in FIT’s 2017 exhibition “Black Fashion Designers.”

Now, her designs have earned a renaissance of interest and admiration. And for a good reason.

“With all the political movements happening right now, that have been building over the last century, people are interested in the history of Black artists and Black creatives in so many industries,” said Elizabeth Way, an assistant curator at The Museum at FIT.

“Black designers have always been working in the industry. There is a legacy there.”

After reading about Ann Lowe, learn about the Kennedy curse that has haunted this famous family. Or, discover the intriguing history of wedding gowns.