In the 1950s and '60s, Asa Earl Carter was a violent white supremacist. But years later, he tried to cover up his racist past — by pretending to be a Native American author.

Forrest Carter’s “memoir” The Education of Little Tree was a sleeper literary hit. Published in 1976, the heartwarming book about growing up with Cherokee grandparents really took off in the late ’80s and early ’90s. It reached the top of The New York Times Best Sellers list and was even recommended by Oprah Winfrey.

But something wasn’t right.

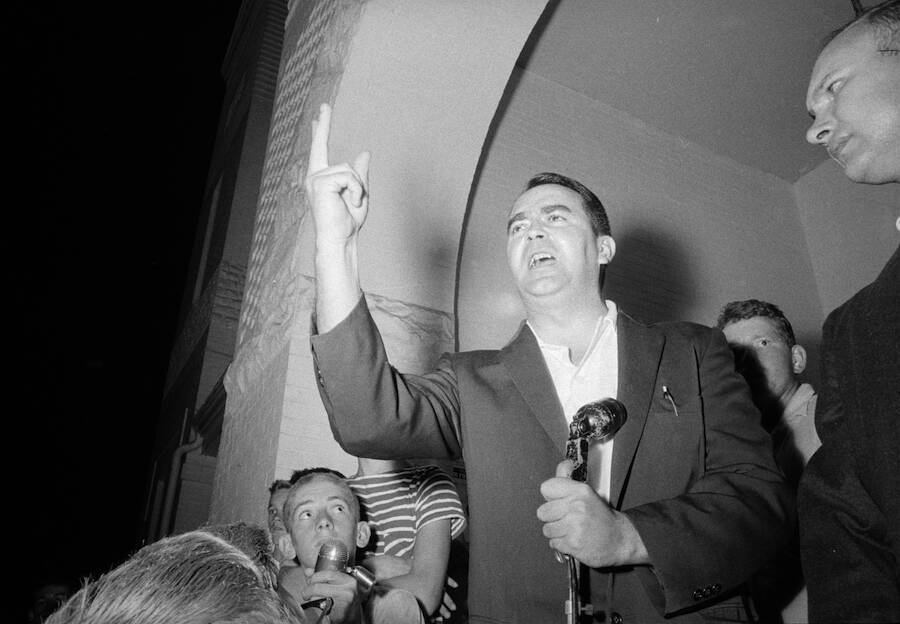

Robert W. Kelley/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesAsa Earl Carter makes a fiery speech in opposition to school integration in Tennessee in 1956.

As it turned out, Forrest Carter had been born Asa Earl Carter. And before he became a “Native American” author in the 1970s, he was a violent white supremacist in the ’50s and ’60s. In fact, Carter’s views were so extreme that even some other racists wanted nothing to do with him.

Here’s how Asa Earl Carter went from penning segregationist speeches to writing feel-good novels under a fake name.

Asa Earl Carter’s Hateful Roots

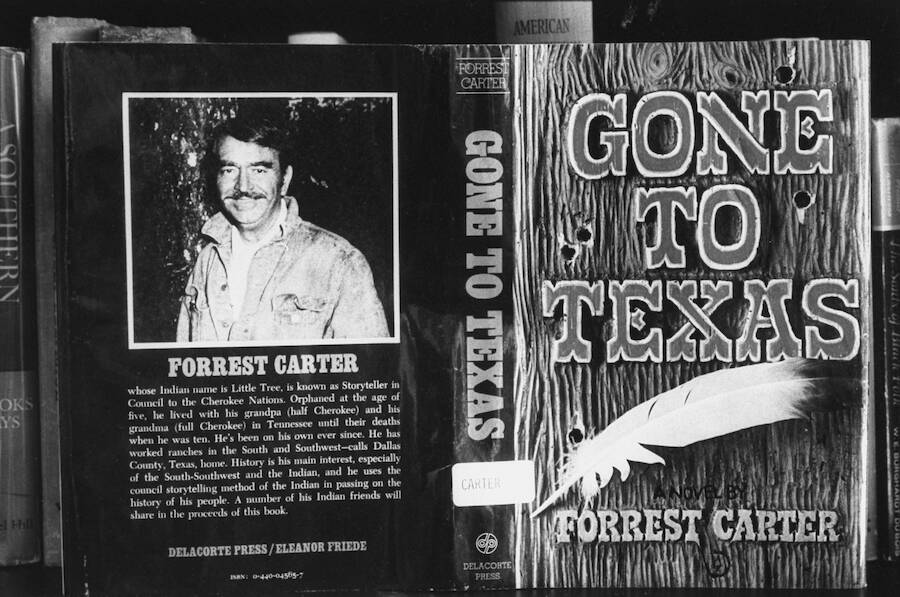

Thomas S. England/The LIFE Images Collection/Getty ImagesThe book cover of Gone to Texas by “Forrest Carter,” who was later outed as the former Klansman Asa Earl Carter.

Born in Anniston, Alabama in 1925, Asa Earl Carter would later claim to have been orphaned at a young age. In truth, he was raised by his parents, Ralph and Hermione, and he had three siblings.

He spent his childhood awed by stories of his ancestors, who had been Confederate soldiers. By the time he graduated high school, Carter had already formed most of his white supremacist views. Joining the Navy to serve in World War II, he complained about fighting a “Jewish” war against the Germans, whom he viewed as similar to his Scotch Irish ancestors.

After serving in the Navy, Carter married, studied journalism in Colorado, and worked at a radio station. In 1953, he moved back to Alabama. Here, in the heartland of racial segregation, Carter would thrive, proclaiming his racist beliefs to an audience who was more than happy to listen to him.

Carter started a newsletter, the Southerner, and used his platform as a radio host at WILD to broadcast his white supremacist views. However, in a sign of things to come, he seemed to have developed a strange soft spot for Native Americans. One of Carter’s friends recalled him saying, “Blacks don’t know what it is to be mistreated. The Indians have suffered more.”

Otherwise, Carter was largely seen as an extremist. Although audiences at the time were receptive to his pro-segregation rhetoric, his anti-Semitism was too much for some to take. He was fired from his radio show.

Refusing to temper his anti-Semitism, Carter formed a “white citizens council” in 1954, which was seen as a more “respectable” alternative to the Ku Klux Klan. But Carter joined the Klan as well. He even started his own paramilitary unit of 100 men: “The Original Ku Klux Klan of the Confederacy.”

Waging A War On Racial Progress

Wikimedia CommonsI 1956, Black jazz pianist Nat “King” Cole was assaulted in Birmingham by the KKK.

Carter didn’t have his radio show anymore. But he made sure that others heard his opinions — by targeting popular musicians.

In 1956, Carter complained to the press that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had used rock and roll music to “infiltrate” Southern white teenage culture.

Carter — described in The New York Times as a “segregation leader” and the “executive secretary of the North Alabama White Citizens Council” — called on jukebox operators to purge their machines of “immoral” records and any records featuring “Negro performers.”

Meanwhile, Carter’s fellow Klansmen went one step further in 1956. When Nat “King” Cole, the famous Black jazz pianist, came to Birmingham to perform, Klan members rushed the stage and assaulted him.

These same Klansmen also savagely beat civil rights activist Fred Shuttlesworth and his wife Ruby. In one particularly gruesome incident, Carter’s followers kidnapped and tortured a randomly chosen handyman, castrating him as a warning to Black “troublemakers.”

Carter wasn’t always present at these attacks. But he openly advocated for violence. As the federal government pushed the South toward integration, Asa Earl Carter vowed, “If it’s violence they want, it’s violence they will get.”

Soon, he would find an even louder mouthpiece for his ideas.

Asa Earl Carter’s Entry Into Politics

Wikimedia CommonsGeorge Wallace infamously blocked the doors of the University of Alabama to deny entry to Black students.

In the early 1960s, Asa Earl Carter found a partner in George Wallace, who had tried to become the governor of Alabama in 1958. Defeated by John Patterson, Wallace was convinced that he lost because Patterson had the support of the Klan. Stung by his defeat, Wallace vowed that he would never be seen as sympathetic to Black Americans ever again.

To reinvent his image, he needed the help of a seasoned hate-monger.

Asa Earl Carter was a natural choice. By 1958, Carter had quit the Klan (calling its new leaders “a bunch of trash”) and turned to politics. He finished last in the race for Alabama’s state lieutenant governor. But he caught the attention of Wallace’s people, who needed someone to help their boss.

It’s unclear whether or not Wallace ever knew Carter personally. But Wallace’s aides admitted that they kept Carter “under wraps” by paying him under the table and keeping him in a back office.

Armed with Carter’s words, Wallace was able to glide to victory as a Democrat in the 1962 gubernatorial election. During his inauguration in 1963, he made national news when he uttered these infamous words: “Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!”

Outside of Alabama, no one knew Asa Earl Carter’s name. But his fiery words would be remembered forever.

In 1968, Wallace tried to soften his image when he ran for president. But Carter saw this as a betrayal. After Wallace lost that race, Carter ran against Wallace in 1970 for the governor’s seat — and finished last. And so he picketed Wallace’s 1971 inauguration with signs like “Free Our White Children.”

He told reporter Wayne Greenhaw that Wallace was a traitor who had betrayed the nation just when it needed him most. “If we keep on the way we’re going, with the mixing of the races, destroying God’s plan,” Carter said tearfully, “there won’t be an earth on which to live in five years.”

Then, Asa Earl Carter simply disappeared. Greenhaw later recalled, “It’s like he just vanished, dropped off the face of the earth.”

The Disappearing Klansman

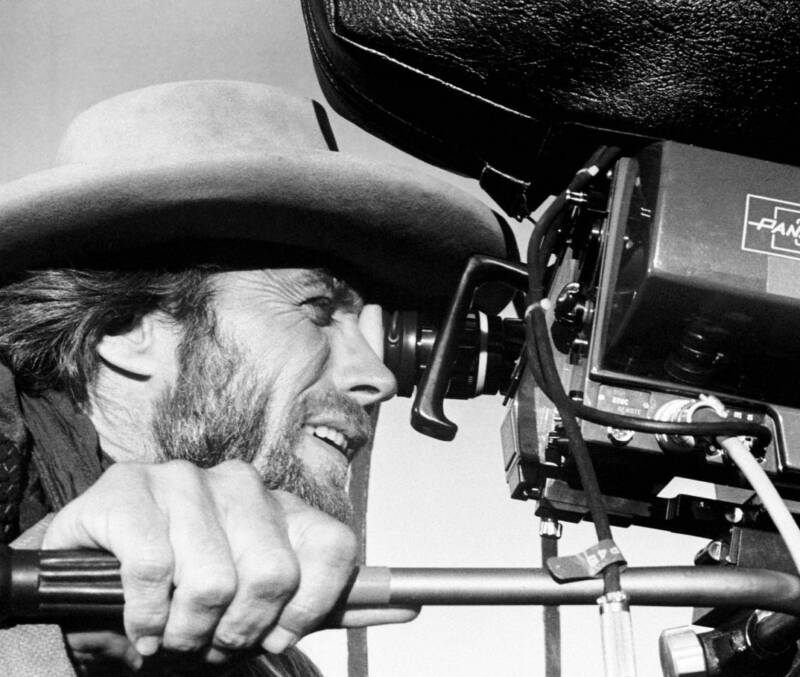

Wikimedia CommonsIn 1975, Clint Eastwood directed The Outlaw Josey Wales, which was based on a novel by Forrest Carter.

Defeated, Carter left Alabama and moved to Florida in the early 1970s. But he spent much of his time in Abilene, Texas, where two of his sons had settled. It was around this time when he began to craft a new identity for himself — to cover up his racist (and very recent) past.

Surprisingly, it worked like a charm. One couple who ran a bookstore in Abilene distinctly remember meeting Carter in 1975. Donning jeans and a cowboy hat, Carter claimed that he was Cherokee and had been raised by his grandparents in a cabin. Since he had dark skin, they didn’t question his claims and said they “liked him from the start.”

But even as Carter assumed a “Native American” persona, he still couldn’t completely let go of his racist ways. In fact, he took the name Forrest in honor of the Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, who had founded the first Ku Klux Klan. But instead of rejoining the KKK, Carter launched himself into a Western-inspired literary career.

In 1972, “Forrest Carter” published the novel The Rebel Outlaw: Josey Wales, which was later renamed Gone to Texas. In the book, a former Confederate soldier loses his family before going on to become the most wanted outlaw in Texas. The book caught the attention of Clint Eastwood, who adapted it into the hit film The Outlaw Josey Wales.

Josey Wales was followed by more books, including The Education of Little Tree, a “true story” about Carter’s childhood with his Cherokee grandparents. The book’s simple message of love for one’s fellow man resonated with readers all over the country. Some readers also enjoyed the themes of nature in the book — and distrust of the government.

But reporter Wayne Greenhaw saw something different. After Carter was interviewed by Barbara Walters in 1975 about his “Cherokee” identity, Greenhaw realized that “Forrest Carter” was really the white supremacist he’d known in Alabama — Asa Earl Carter.

“She’d ask him questions and he’d mumble these answers,” Greenhaw recalled. “He said he wrangled horses and, when he was in Oklahoma, he was the storyteller to the Cherokee Nation.”

Greenhaw described his reaction as “bumfuzzled.” He eventually got in touch with Carter, who said, “You don’t want to hurt old Forrest, do you now?” Greenhaw replied, “Come off of it, Asa, I recognize that voice.”

The Unmasking Of Forrest Carter

Greenhaw described his revelation in The New York Times in 1976, but the article had little impact. Many fans of Carter’s work either didn’t believe or didn’t want to believe the exposé.

And for his part, Forrest Carter fervently denied being Asa Earl Carter. He would maintain that he was Forrest, the Cherokee cowboy with a knack for writing, until his death in 1979 following a drunken fight with one of his sons.

It wasn’t until 1991 when the former Klansman was finally unmasked.

In a scathing article for The New York Times, historian Dan T. Carter revealed the real Forrest Carter: “Between 1946 and 1973, the Alabama native carved out a violent career in Southern politics as a Ku Klux Klan terrorist, right-wing radio announcer, home-grown American fascist and anti-Semite.”

Noting numerous fabrications in Carter’s story, such as the fact that the “Cherokee” words in The Education Of Little Tree were completely made up, the historian was able to show that Forrest was a fraud. On top of that, the Alabama address that “Forrest” had used in the copyright application for Josey Wales was the same address that Asa had used in that state.

Carter’s widow had long kept his secret.

But after the Times article came out, she soon admitted to the fraud. As for Asa Earl Carter’s physical transformation, former friend Ron Taylor explained it as such: “He just pulled up out of the Choccolocco Valley, tanned himself up, grew a mustache, lost about 20 pounds, and became Forrest Carter.”

Any details beyond that remain largely a mystery. Carter’s family revealed little about Carter’s double life. It’s also unclear whether he had any Cherokee ancestry at all. So fans were left with countless questions: Did Carter change his ways? Had they simply been fooled all along? Worse yet, did they have more in common with the “real” Carter than they thought?

There’s no question that Carter left behind a bizarre — and extremely controversial — legacy. Perhaps the most fitting tribute to this came in the form of a 25th-anniversary publication of The Education of Little Tree. This time, the words “a true story” were finally erased from the book’s cover.

After learning about Asa Earl Carter, uncover the true story of Mary Church Terrell, the courageous Black activist who championed equal rights for women and Black Americans. Then, take a look at terrifying images of the KKK during their infamous march on Washington.