From 1933 until they were caught in 1942, the Red Orchestra group battled Nazi Germany behind the scenes.

When the Nazis began rising to power in the 1930s, many Germans did not try to stop them. But the Red Orchestra was different. The people who joined this secret resistance group — artists, journalists, and government officials — were all determined to take Hitler down. And scores of members gave their lives in order to do so.

But after World War II, the Red Orchestra’s efforts were distorted by history. This was largely due to the group’s name — and its obvious link to the Soviet Union. But it was actually the Gestapo who came up with this name in the first place — as they sought to discredit the organization as a Soviet espionage group that was full of “Communist traitors.”

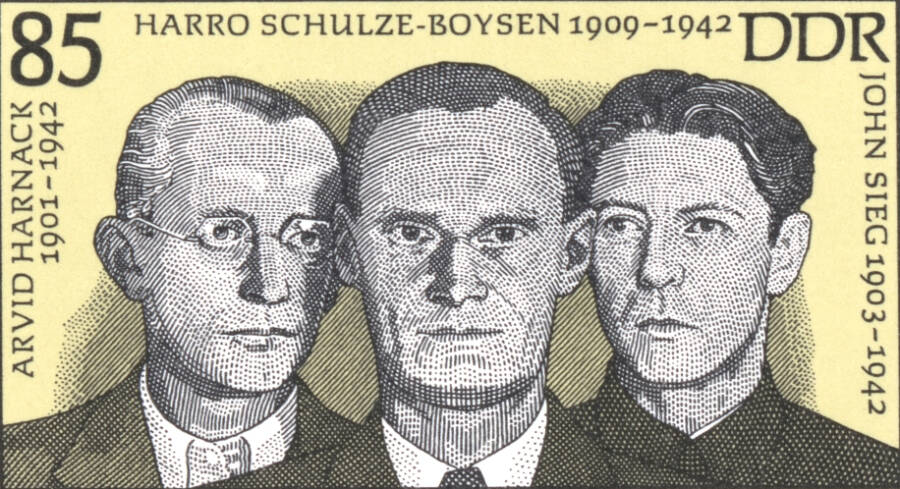

Wikimedia CommonsHarro Schulze-Boysen, Arvid Harnack, and Mildred Fish-Harnack were a few famous leaders of the Red Orchestra.

In actuality, the truth was far more complex, tangled in the chaos of conflict and smothered by the impact of the Cold War. While Red Orchestra members certainly helped the Soviet Union in an effort to end Adolf Hitler’s dictatorship, that didn’t mean that everyone in the group was a Communist.

Indeed, the group was made up of people who came from a variety of political backgrounds. Some would describe themselves simply as patriots. Adding to the confusion is the fact that the Red Orchestra contained a few separate units — including the Schulze-Boysen/Harnack group, the “Red Three,” and the Trepper Unit — and all of these were loosely organized.

Furthermore, not all of the people who were said to be part of the Red Orchestra were even based in Germany. Some members never met associates who worked in other countries — and some only knew them by secret code names.

This is the complicated yet inspiring story of the Red Orchestra, the rebel network that waged a secret war against the Nazis.

The Schulze-Boysen/Harnack Group: Ordinary Germans Decide To Fight Back

Wikimedia CommonsIn East Germany, the members of the Red Orchestra were hailed as heroes after World War II.

In 1933, Arvid Harnack and his wife Mildred Fish-Harnack helped found an underground group to resist Nazism in Berlin. At the time, Arvid was a German senior executive officer in the Reich Ministry of Economics, and Mildred was an American-born woman with experience as an English teacher (who had settled in Germany with Arvid).

The couple used their secret group to help Jews, document Nazi acts of violence, and distribute anti-Hitler pamphlets. Arvid helped lead the group alongside Lt. Harro Schulze-Boysen — who was a member of Hermann Goering’s staff. This was a somewhat odd pairing, since Harnack and Schulze-Boysen had pretty different personalities.

While Harnack was seen as a quiet and studious Marxist economist, Schulze-Boysen was a liberal magazine publisher and the son of a prominent naval family who led a Bohemian lifestyle. But what they did have in common was a shared contempt for the Nazi regime.

Through their wide webs of friends and contacts, they built a home-grown ring of rebels who would frustrate the efforts of the Nazi police organization for years. This ring eventually counted more than 150 members — and about 40 percent of them were women.

Far from passive bystanders, these women played a critical role in the group’s missions. Mildred Fish-Harnack used her experience as an English instructor to recruit resisters to travel abroad — and lend a hand to émigrés.

She also provided cover for her husband as he met with the first secretary of the American embassy in the forests of Berlin. Because of this, America was kept informed on the state of the Third Reich.

While Arvid and Mildred were more often privy to economic secrets, Schulze-Boysen had access to top-secret information on military tactics. By the early 1940s, both Arvid Harnack and Harro Schulze-Boysen were passing on intelligence of military importance to the Soviet Union.

But they weren’t the only ones.

The Trepper Unit And The “Red Three”: Spies In Other Countries Join The Fight

Wikimedia CommonsIn closets and back rooms of nondescript houses in Brussels, the Soviet-backed agents of the Red Orchestra transmitted thousands of messages containing key military secrets to Moscow.

The unit of the Red Orchestra in Nazi Germany is arguably the most well known one today, but the Orchestra also operated in other countries. Leopold Trepper’s unit was a famous example of that.

Trepper was a Polish-Jewish exile who had developed an interest in Communism from an early age. His interest did not wane, even in the turbulent years following World War I. After a period of living in Palestine, he had joined the Soviet military intelligence (GRU) by the mid-1930s.

As World War II loomed, Trepper’s Soviet handlers put him to work. He created a fake business as a cover — the “Foreign Excellent Raincoat Company” — and set up operations in Brussels. Before long, he had rings set up not only in Belgium but also in other countries like France and Holland.

By the early 1940s, Trepper oversaw seven GRU units, which spanned throughout the continent and collected information from within German-occupied Europe. While heading a clandestine radio service, Trepper boasted high-ranking agents in the German military machine. Because of this, he was able to pass on vital information about German military movements.

However, the Soviet government wasn’t always open to receiving his intelligence. Many Soviets clung to the belief that the Germans would adhere to the terms of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact — a non-aggression pact. When Trepper acquired evidence of Germany’s plans to invade the Soviet Union in 1941, the Soviet military attaché in France told Trepper, “My poor fellow, I will send your dispatches, but only to make you happy.”

Wikimedia CommonsSpies like Alexander Radó were crucial to the Soviet victory on the Eastern Front.

As Trepper toiled to collect information and convince Moscow of its importance, another Soviet-backed group had been diligently working in neutral Switzerland since 1936. Nicknamed “Red Three,” it was headed by an exiled Hungarian named Alexander Radó.

In 1939, Radó joined forces with Rudolf Roessler, a German anti-Nazi living in Lucerne, Switzerland. Roessler boasted several sources in Germany — some of whom were disillusioned with Hitler. Many of these sources likely confided in the Swiss General Staff, who then relayed it to Roessler.

In 1943, the “Lucy Ring” — so named because Roessler was based in Lucerne — helped lead the Red Orchestra to one of their greatest successes. As the Germans were preparing to attack the Red Army in Kursk, Ukraine, the Lucy Ring spies gained advance warning of the offensive.

They passed on crucial information about the planned attack — known as Operation Zitadelle. And before long, the Soviets knew almost exactly what the Germans were planning before it even happened.

At the Battle of Kursk, the work of the Swiss spy ring paid off: The Germans’ attack failed, and the Soviet Union had finally crushed Hitler’s dream of conquering Russia.

The Final Notes Of The Red Orchestra

Wikimedia CommonsThe Red Orchestra played a key role in helping the Soviets thwart Operation Zitadelle. But by that point, many of the members had already been arrested.

But before things started looking up for the Red Army, the invasion of 1941 had been a rude wakeup call for them. After all, they had received multiple warnings from the Red Orchestra, which turned out to be accurate.

Determined to mine the Red Orchestra for more intelligence, the Soviets sent an ill-conceived message to spies associated with Trepper. This message contained the addresses of three key players in Berlin’s Red Orchestra. When Trepper learned of the shockingly irresponsible breach, he responded, “It’s not possible. They have gone crazy!”

Indeed, a major reason why the Red Orchestra was found out was due to errors on the part of Soviet intelligence. But as dangerous as the message with the addresses was, it was not the only radio communication that the Germans had successfully intercepted.

During 1942, waves upon waves of arrests pounded the resistance networks. Schulze-Boysen and his wife were detained near the end of August, followed by the Harnacks in early September. Dozens of their fellow spies were also rounded up in the following weeks.

Trepper was arrested in December, and the Nazis gleefully reported that he betrayed his associates after being captured. But it’s unclear exactly how helpful Trepper was to the Nazis. Some believe he may have only given up a few names in an effort to protect other associates.

In any case, Trepper was able to escape the Nazis’ clutches by 1943 — and he even attempted to rebuild the Red Orchestra once he was free. But by that point, the network had largely dissolved and the movement was over. Still, he had a far happier ending than other members.

Wikimedia CommonsPlötzensee Prison in Berlin, where thousands of opponents of the Nazis, including the Harnacks and the Schulze-Boysens, were executed.

The Schulze-Boysens, the Harnacks, and more than 50 other members of the Berlin-based group were tried for “treason” and sentenced to death. Mildred Fish-Harnack’s last words before she died were: “And I have loved Germany so much.” She was beheaded in Plötzensee Prison in February 1943, two months after her husband was executed.

Despite the Red Orchestra’s efforts to take down Hitler, they weren’t always viewed positively by other groups who had fought against him. And for decades afterward, the Red Orchestra’s legacy was distorted due to the persistent belief that the members were all “Communist traitors.”

While this belief was first spread by the Nazis, it was also perpetuated by the Allied secret services — and even by the CIA. Because of this, many surviving members were wrongly labeled as Cold War spies.

Political disagreements also played a role in the distortion. To West Germany, the Red Orchestra was an uncomfortable reminder that resistance had been possible — and that too many people had let Hitler do his bidding. In East Germany, they were seen as Marxist heroes, which the government used to give legitimacy to the Soviet rule.

But in the years after the reunification of Germany, this distortion has begun to fade. And the Red Orchestra is now understood as a large, complex group of people who, despite differing backgrounds, aims, and politics, shared one abiding belief: They would do whatever it took to stop Hitler and the Nazis.

After learning about the forgotten Red Orchestra, find out more about Sophie Scholl and the White Rose, the heroic young Germans who dared to defy Hitler. Then, learn about Claus Von Stauffenberg, the officer who led the effort to topple the Nazi regime from within.