Massive herds of prehistoric rhinos known as Teleoceras major once roamed the plains of present-day Nebraska — then many of them died out in dramatic fashion when the nearby Yellowstone volcano erupted and the region was blanketed in ash that piled up as much as a foot high.

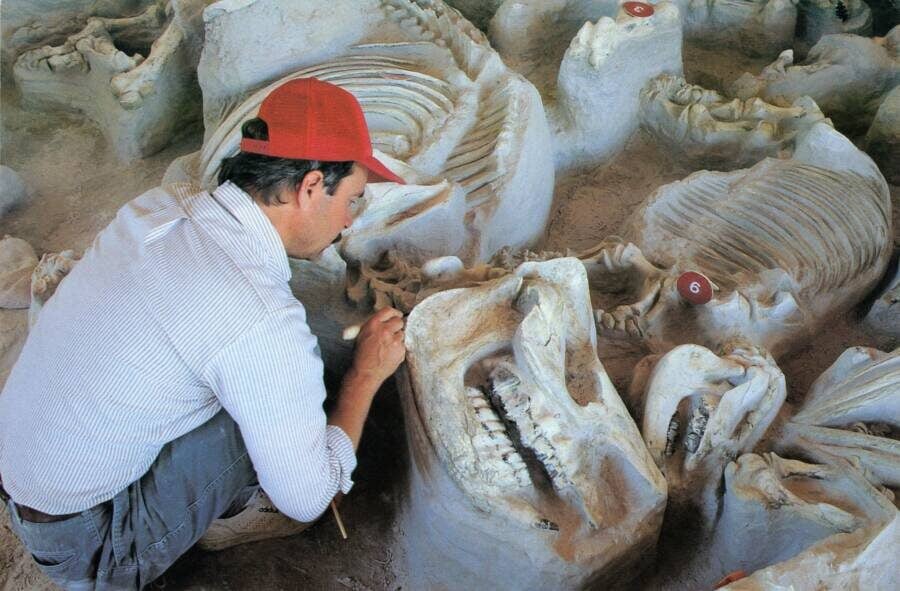

John Haxby/The University of Nebraska State MuseumThe fossils of prehistoric rhinos at Nebraska’s Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park.

Roughly 12 million years ago, North America’s plains were vast, grassy savannas teeming with life that was very different from the fauna of today. The climate was warmer and wetter than it is now, with rivers and scattered woodlands that supported prehistoric animals like elephants, camels, and rhinos.

One rhino herd, made up primarily of the species Teleoceras major, lived in the region in large groups — until a deadly eruption from the nearby Yellowstone volcano slowly suffocated and buried them beneath layers of ash.

In 1971, researchers uncovered a massive rhino graveyard in northeastern Nebraska that contained the fossils of more than 100 individuals who died during this disaster. Today, the site is known as Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park, and it’s now the focus of a remarkable new study.

A group of researchers from the University of Cincinnati has used isotopic analysis to reveal pivotal information about how these prehistoric rhinos lived and died, as well as what led them to form uncharacteristically large herds.

The Discovery Of A Massive Herd Of 12 Million-Year-Old Rhinos In Nebraska

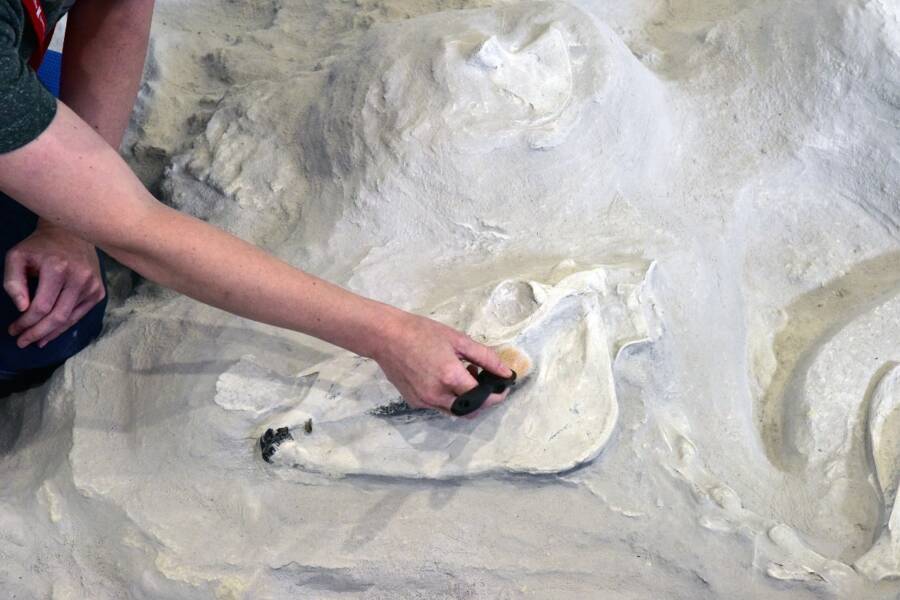

Ali Eminov/FlickrAshfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park, located in northeastern Nebraska.

Upon its discovery in 1971, Ashfall Fossil Beds was found to contain a massive prehistoric rhino graveyard. The site held the remains of over 100 rhinos from the Teleoceras major species who lived in the area during the Middle Miocene, a geological period spanning from 16 to 11.6 million years ago.

At first, researchers were puzzled by the discovery and left asking how such a large number of these animals ended up in the same place and why. Their fossilized remains pointed to a slow death, likely brought on by an eruption from the nearby Yellowstone volcano.

“That ash would have covered everything: the grass, leaves, and water,” lead author of the new study Clark Ward said in a statement from the University of Cincinnati. “The rhinos likely weren’t killed immediately like the people of Pompeii. Instead, it was much slower. They were breathing in the ash. And they likely starved to death.”

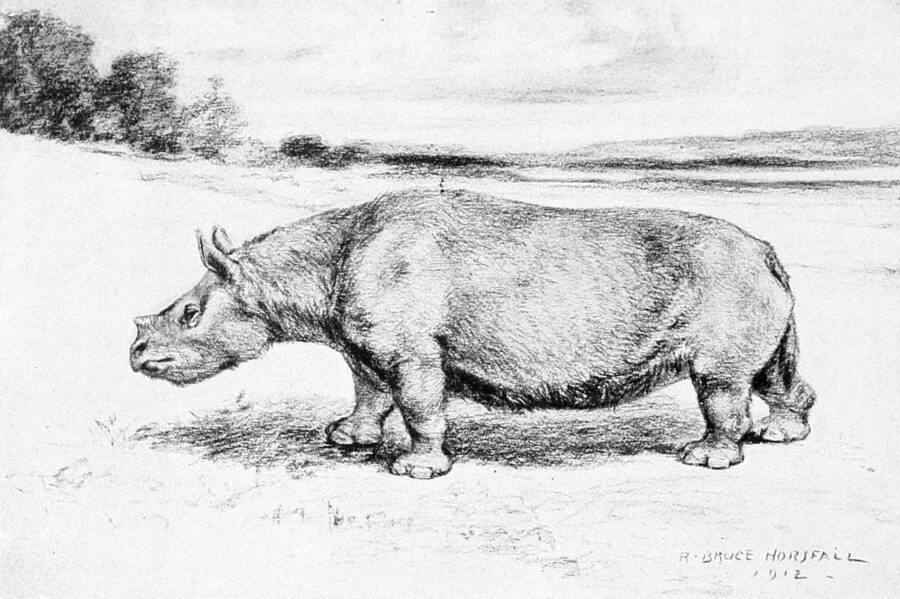

Public Domain An illustration of Teleoceras fossinger, a similar prehistoric rhino species that lived in North America between 20 million and 7 million years ago.

The species discovered at the Ashfall Fossil Beds State Historical Park primarily belonged to Teleoceras Major, a group of prehistoric rhinos with one horn, barrel-shaped bodies, and stubby legs — similar to a modern-day hippopotamus.

During initial excavations, researchers discovered that members of the herd struggled with health problems, particularly bone disease as a result of lung failure from the respiration of volcanic ash.

The majority of the herd was female and of breeding age. One specimen was found to be pregnant at the time of death, with a fetus still in her birth canal. Another fossil shows a young calf in a suckling position under its mother.

Decades of excavation have unveiled key facts like these, but several questions still remained — questions that could only be answered with chemical analysis.

New Research Reveals More About The Lives And Deaths Of Nebraska’s Prehistoric Rhino Herd

Ali Eminov/FlickrA researcher examines the rhino fossils at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

Supported by the University of Cincinnati, the Geological Society of America, the Western Interior Paleontological Society, as well as the University of Nebraska State Museum and the Meek Fund, three researchers sought to answer the question: Why were so many of the Teleoceras major rhinos concentrated in one place at their time of death?

Today, rhinos’ social behavior is highly dependent on their species. While some species, like the white rhino, live in groups of up to 15, other species are more solitary and prefer to live alone outside of the mating season.

As described in their new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers used isotopic analysis of the rhino’s teeth to identify climate pressures or other reasons that might explain their unusually large herd size.

Specifically, the research team examined the ratios of isotopes of strontium, oxygen, and carbon in the rhinos’ teeth to track their movements in different environments.

When a rhino eats grasses or leaves, the isotopes in that plant material can be left behind in the animal’s teeth. By comparing those isotopes to ones found in the soil of different areas, researchers can track where the animals ate, and therefore where they migrated.

While carbon can help identify what kinds of vegetation the rhinos consumed, strontium can detail where the animals ate, and oxygen can provide information about rainfall and climate trends.

“By studying carbon in the animal, we can reconstruct carbon in the environment to understand what kinds of vegetation lived there,” Ward said. “We can use [oxygen] to reconstruct how wet or dry the environment was. And strontium tells us where the animal was foraging because the ratio of isotopes is related to the soil and supporting bedrock.”

John Haxby/The University of Nebraska State MuseumA researcher works on fossils at Ashfall Fossil Beds.

The chemical analysis revealed that this rhino herd did not migrate vast distances. Instead, they remained stationary in their large herds — a far cry from the behavior of modern-day rhinos.

“We found they didn’t move very much,” Ward said. “We didn’t find evidence for seasonal migration or any evidence of a response to the disaster.”

Researchers believe the rhino herd had already gathered in large numbers before the Yellowstone eruption. And when their climate became increasingly more inhospitable, they died as they lived: together.

After reading about these prehistoric rhinos, dive into the stories of 11 of Earth’s most unbelievable prehistoric creatures. Then, read about 10 of the most terrifying animals from the prehistoric era that weren’t dinosaurs.