Automats were efficient vending machine-style restaurants that signaled to many Americans that the future in dining had arrived. So what happened to them?

At the turn of the century, New Yorkers rushed to a new kind of dining establishment, one they felt represented all the sleekness and efficiency of a future in chrome: the Automat.

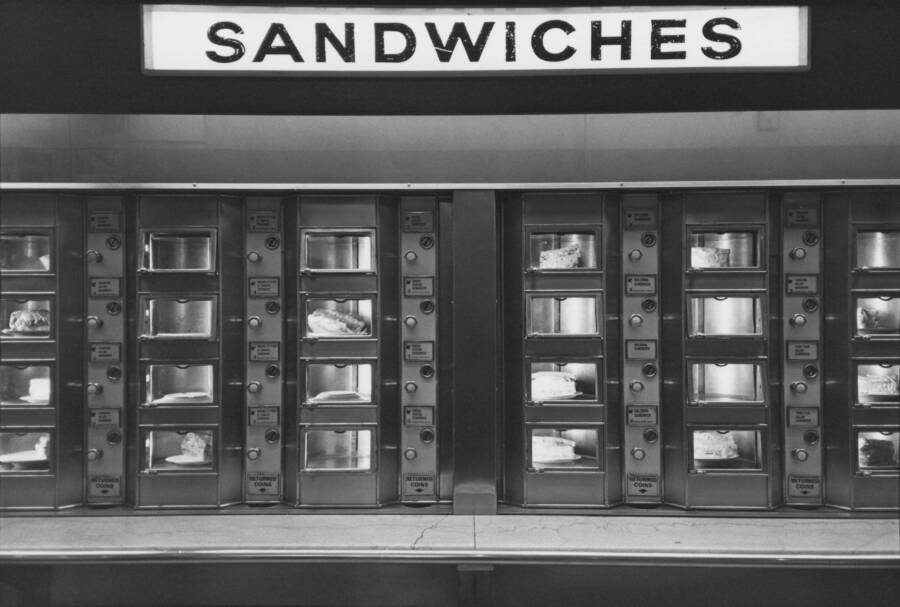

As a sort of ancestor of the vending machine, Automats were a wall of coin-operated cubbies that contained hot food and beverages behind a glass window. They provided quick and delicious meals to hundreds of thousands of diners a day at low prices, thanks to waiter-less service.

The Automat was supposed to catapult dining into the future, but it was eventually outcompeted by the rise of faster food options. This is the story of how the “future of dining” quickly became a thing of the past.

America Welcomes The First Automat

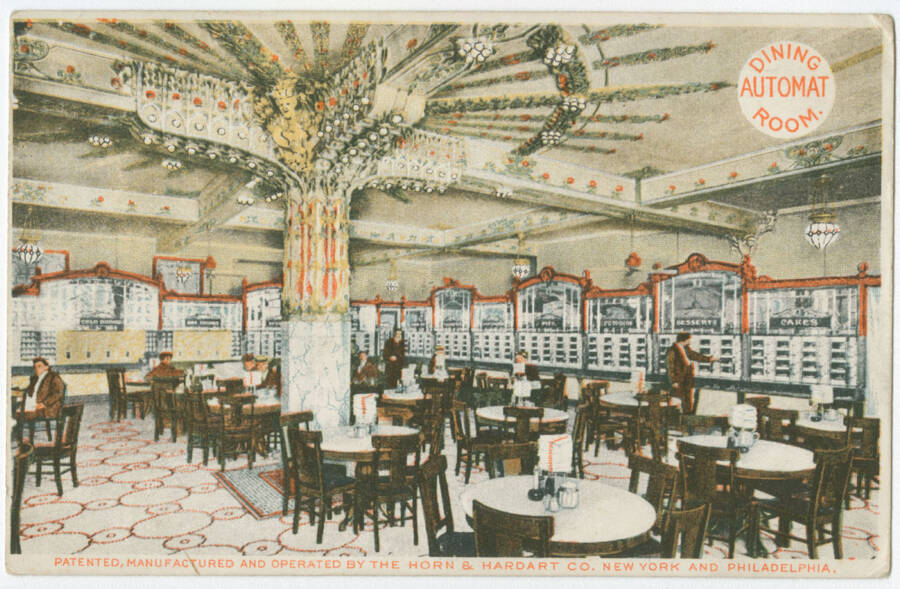

Library Company of Philadelphia/Wikimedia CommonsBy the 1950s, cafeteria-style restaurants with coin-operated vendors like this were all the rage.

The first Automat appeared in Berlin in 1895 in an Art Nouveau-style dining room. Integrating technology and the dining experience appealed to modern customers, and so the Automat soon caught on across the Atlantic.

In 1902, Philadelphia-based restauranters Joseph Horn and Frank Hardart opened their first Automat named Horn and Hardart. They had already established a small cafe of the same name that sold cheap coffee and quick meals since 1888. Theirs was the first Automat in the country and it was an instant hit.

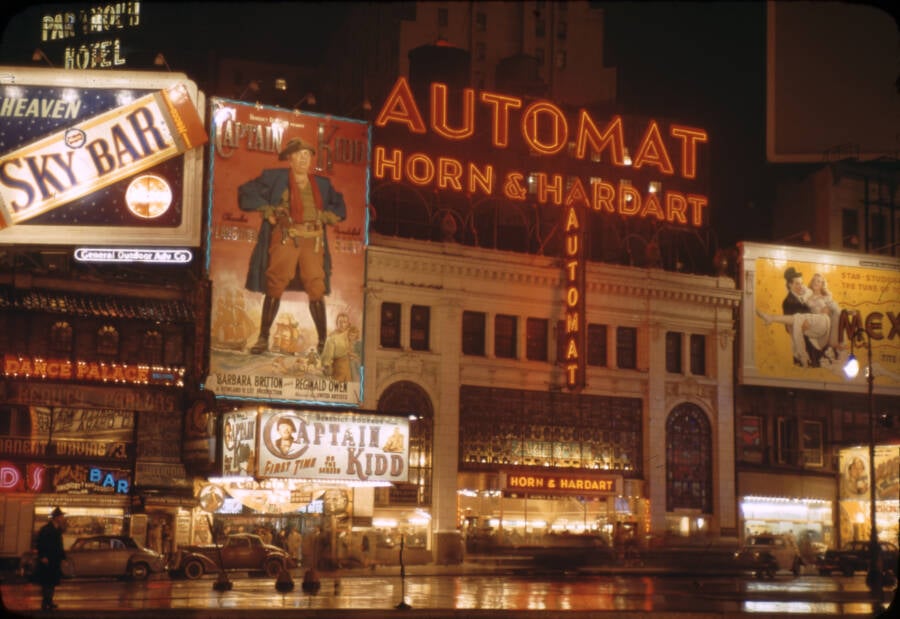

By 1912, Horn and Hardart opened a second location in Manhattan’s Times Square and deemed it “the new method of lunching.” White-collar businessmen, construction workers, and secretaries alike sat next to each other in the communal dining area, creating a very different atmosphere from the more exclusive restaurants in the city. Even celebrities like Audrey Hepburn opted for the Automat.

By the 1950s, Horn and Hardart operated over 100 locations in New York City alone. During its heydey, over 800,000 people ate at a Horn and Hardart Automat each day, making it the world’s largest restaurant chain.

How The Automat Modernized Food Service

Getty ImagesAn Automat offered an entire meal complete with an entree and sides for just 25 cents.

A precursor to fast food, Automats promised diners an efficient and affordable dining experience in a communal atmosphere.

The shiny modern machine combined well with the growing sanitation movement and diners loved being able to analyze their dishes before choosing them.

Plus, customers didn’t even have to interact with a human. Rather than order from a waiter, diners inserted a coin into a machine, turned a chrome and porcelain knob, and received a full meal in moments.

Diners in a real hurry could even eat “perpendicular meals” at stand-up counters inside the restaurant.

But Automats weren’t totally automatic. Behind the Automat, hidden workers cooked and replaced dishes, rushing to keep up with the demand.

What’s On The Menu At “Automatic Restaurants”

Automats served up home-style comfort food including both hot and cold entrees, desserts, and beverages. Many offered an entire wall of pies, including savory pot pies and sweet fruit pies, or mac and cheese, mashed potatoes, salads, and sandwiches.

Horn and Hardart promised the freshest food possible, carting away any leftover food at the end of the day to cheap outlet stores. With nearly 400 items on the menu, Horn and Hardart also promised something for every diner, from picky children to Wall Street bankers.

A little boy buys milk from an Automat in Stockholm. The global fad began in Berlin and was brought to the States when restaurateurs Horn & Hardart purchased the design for their Philadelphia cafe in 1902.

But the most popular item at Horn and Hardart was the coffee. The restaurant boasted freshly-brewed batches every 20 minutes and the owners ordered coffee from a different Manhattan location each day to test for freshness.

By the 1950s, upwards of 90 million cups of coffee were purchased from a Horn and Hardart’s every year — and at just a nickel per cup.

The Workers Behind The Machine

The name “Automat” derives from the Greek word automatos, which means “self-acting.” But these mid-century machines didn’t run on their own, instead, restaurant employees kept the machine running smoothly from behind the glass and metal walls.

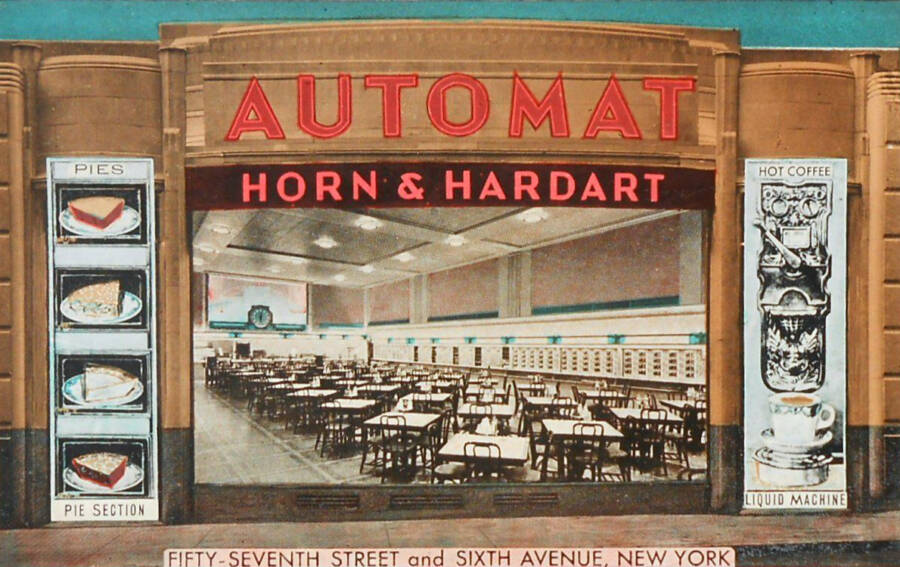

Horn & Hardart/Wikimedia CommonsA postcard advertises a Horn and Hardart location on 57th Street in Manhattan.

One assembly line of workers baked and cooked while another line filled empty slots on the machines with new dishes. A third set of workers cleaned dirty dishes.

The most visible employees at the Automat were “nickel throwers” – women stationed in glass booths who handed out change to operate the machines.

In 1929, cooks employed by Horn and Hardart made around 40 cents while busboys made just 20 cents an hour, well below today’s minimum wage when adjusted for inflation. Many workers put in 50 hour weeks with no overtime or paid vacations. Automats thus faced a backlash from the labor movement.

In 1937, the AFL-CIO picketed Horn and Hardart locations in New York City, demanding better treatment for workers. Another strike followed in 1952 and Horn and Hardart found themselves raising the price of their coffee to accommodate the salaries of their workers.

This would in part spell the beginning of the end to the Automat.

The Decline – And Return – Of The Automat

Automats seemed like the wave of the future in 1910, but by 1960, they were considered outdated. At the turn of the 20th century, the first Automats only competed with full-service restaurants, but by the century’s final decades, they were outcompeted by faster food options like takeouts and drive-thrus.

The Automat’s decline came as consumer tastes changed. By the 1960s and beyond, many customers preferred to grab food and go rather than to sit down in a cafeteria. Customers thus chose the modern hamburger, a portable meal, over the homestyle menu at an Automat that still required a customer to sit and eat.

Andreas Feininger/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty ImagesA Horn & Hardart Automat in Times Square in 1945.

Chains like McDonald’s and Burger King replaced the meatloaf-and-pie menu of the Automat. In fact, in the 1970s, Horn and Hardart replaced several of their own Automats with Burger King franchises.

Horn and Hardart closed its final location in the 1990s, but the concept didn’t stay dead for long. In 2015, Eatsa opened a 21st-century Automat in San Francisco where customers could order on an iPad and pick up their custom quinoa bowls from a wall filled with glass compartments.

But even Eatsa soon closed its doors, just four years later.

Although the era of the Automat has ended, it is largely to thank for the birth of the fast-food movement.

The Predecesor Of Fast Food

Barbara Alper/Getty ImagesA Horn & Hardart vending machine still standing in 1980s New York.

The heyday of the Automat overlapped with the rise of fast-food drive-thrus and take-outs for a reason. Those chains adapted the Automat’s emphasis on lower labor costs and affordable prices.

Horn and Hardart pioneered a streamlined method for making large amounts of food in a short period of time and at an affordable price. By removing waiters, Automats created a “tip-free” dining experience which fast-food chains soon replicated. It seemed drive-thrus were a natural next step following the Automat.

Indeed, fast food and fast-casual restaurants stand as the memorial to the Automat’s promise of convenient, efficient dining.

The Automat may have faded, but fast food lives on. Learn about the surprising history of fast food restaurant founders and then, check out these vintage menus from the heyday of the automat.