Bethlem Royal Hospital in England was the first facility of its kind to treat people with mental illness — but poor management and funding turned it into a chaotic institution that came to define the word "bedlam."

If you were to visit the Bethlem Royal Hospital circa the 15th century, it would look like a scene out of American Horror Story.

As the only institution in Europe that handled society’s “rejects” — namely the mentally or criminally unwell — for the vast majority of European history, Bethlem was severely overcrowded and under supported.

It did not, treat patients with a kind and affirming hand. In fact, quite the opposite happened; patients were subjected to horrendous cruelty, experimentation, neglect, and humiliation — all of which were entirely socially acceptable up until the 20th century.

As such, the term “bedlam,” which is define as “chaos and confusion,” was coined as a descriptor for the Bethlem Asylum during the height of its malfeasance in the 18th century. Discover the disturbing story of the institution that created a term for utter mayhem.

The Founding Of Bethlem Royal Hospital

Wikimedia CommonsBethlem Royal Hospital in 1896.

Established in 1247, Bethlem Royal Hospital was the first of its kind in Great Britain. Never before had there been a place for those with mental illness, physical disability, and a criminal history to be adequately locked away from society.

The building itself was an architectural marvel at the time. Rebuilt in the 1600s and designed with Louis XIV’s Tuileries Palace in Paris in mind, Bethlem Royal Hospital featured sprawling, tree-lined gardens and walkways.

But even though it was referred to as a palace, it quickly became known for the less than marvelous goings-on inside.

Patients came to Bethlem suffering from complaints such as “chronic mania” or “acute melancholy,” and people were just as likely to be admitted for crimes such as infanticide, homicide, and even “ruffianism.”

Being admitted, then, didn’t necessarily mean a person was well on their way to being rehabilitated since “treatment” at this facility implied little more than isolation and experimentation.

If the patient managed to survive the asylum at all, they and their families were typically worse for the wear by the end of their stay. Patients were subjected to “treatments” such as “rotating therapy,” wherein they were seated in a chair suspended from the ceiling and spun as many as 100 rotations per minute.

The obvious purpose was to induce vomiting, a popular purgative cure for most ailments during this period. This was because medieval physicians believed that mental illness existed in the body and not in the mind and could therefore only be exorcised through rigorous activity.

Incidentally, the resulting vertigo in these patients actually contributed a large body of research in contemporary vertigo patients. At least their torture was not all for naught.

Beyond the social mores of the time, however, it was a lack of funding and resources that explained why Bethlem became the notorious Bedlam.

How The Hospital Became Bedlam

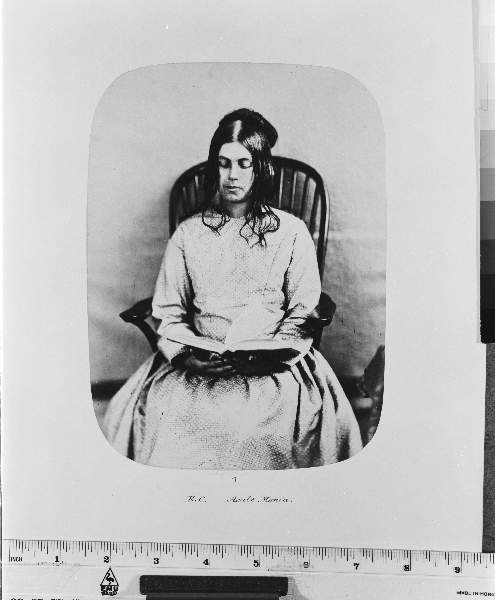

Museum Of The MindEliza Camplin — admitted for acute mania.

By the 1600s, the hospital descended into mismanagement and chaos. As the only mental health facility in Britain up to that time, Bedlam was dependent upon government funding and patient donation.

It was poorly funded by the government nonetheless and heavily relied upon the financial support of a patient’s family and private donors, but many of the patients admitted came from poverty or the middle class.

And uneducated as many of the patients were, they became victims not only to whatever mental infirmities they possessed but a society that was repelled by them. Indeed, the hospital was so notoriously abusive that it was even referenced in plays by Shakespeare and Thomas Middleton.

By the 18th century, Bedlam had become less of a hospital and more a sideshow. People came from all over to see the patients at Bethlem Royal Hospital, some even arranging holidays around it.

Indeed, according to the BBC, the hospital saw 96,000 visitors a year.

Of course, none of these patients were actually “freaks,” but since Bedlam was so fiscally reliant upon the money guests would pay to see them, patients were certainly driven to behave outlandishly.

Additionally, the hospital fell into disrepair as its patient population boomed. The 1601 Relief of the Poor act stated that poor people unable to work could be cared for by the church, while the rest had to go to workhouses or prisons. As such, beggars and petty criminals often feigned insanity in order to avoid being sent there, thus overcrowding the already chaotic Bedlam.

The “Bedlamites,” as they were nicknamed, were subjected to horrific treatments, both experimental and some downright cruel, and were often desired only for the study of their corpses. Others were simply thrown into a mass grave on Liverpool Street.

Indeed, it wasn’t until more recently that researchers have learned just how disturbing the conditions at the hospital were. In 2013, construction workers at the hospital unearthed a startling mass grave of some 20,000 patients. The oldest date back to the 1500s.

Trying To Turn The Hospital Around

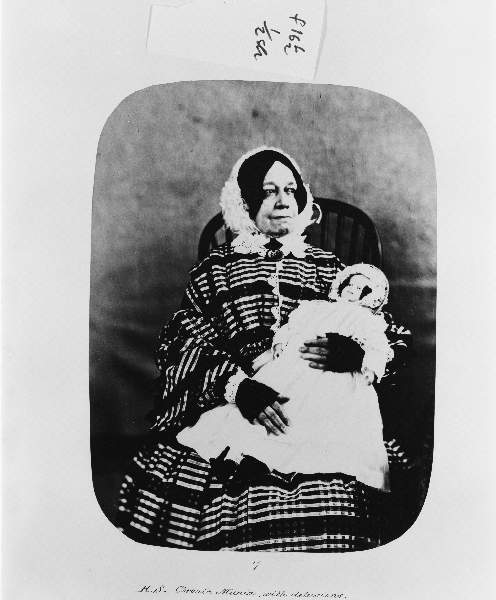

Museum Of The MindHannah Still — admitted with chronic mania, delusions.

In 1815, the British House of Commons Select Committee on Madhouses examined the conditions under which county asylums, private institutions, and charitable asylums treated their patients. The results were shocking.

The current Principal Physician at Bedlam, Thomas Monro, was consequently forced to resign when it was discovered that he was “wanting in humanity” toward his patients.

By the mid-1800s, a man named William Hood who had become a physician in residence at Bedlam decided the hospital needed to be completely changed. He hoped to create actual rehabilitation programs which would serve the hospital’s patients rather than the administrators.

Hood pushed for a separation between patients who were mentally ill and those institutionalized for crimes. He was later knighted for his service to this post.

During World War II, Bethlem Royal Hospital was moved to a more rural location, which was meant to improve the quality of life for its patients. The move also helped to rid the institution of its horrendous legacy. Though, thanks to the Museum of the Mind archives, we are able to get a glimpse of the haunted faces of Bedlamites, as seen throughout this article.

Many of them were photographed upon their admission, with a note or two about their “diagnosis.” One wonders, looking at these photos today, how many of these patients survived Bedlam — and if they did, if any of them were ever truly well again.

Though the historian Roy Porter called the Bethlem Hospital “a symbol for man’s inhumanity to man, for callousness and cruelty,” a 1997 campaign to “reclaim” it has seen that its terrible legacy be rewritten.

Today, the hospital does not shy away from its disturbing history, and instead, features its own art gallery displaying work of current and former patients.

If you enjoyed this fascinating look at the history of Bethlem Royal Hospital and the real story behind the word “bedlam,” check out our other posts on interesting facts. Then, discover the unbelievable reasons people were sent to mental asylums in the 19th century.