Beheading has a long history, and it might have a long future. Find out the who, when, why, where, and how of one of humanity's worst execution methods.

On the morning of February 8, 1587, Mary Queen of Scots mounted a public block and was put to death on the orders of her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I of England, marking the end of one of history’s most famous disputes.

After 18 years of confinement in one fortified house after another, Mary blessed her executioners for “mak[ing] an end to all my troubles,” and even managed to fire off a few one-liners before the sentence was carried out.

That sentence was beheading, and it’s been one of humanity’s favorite execution methods since the first clever caveman figured out how to make troublesome cave neighbors shut up once and for all with the stroke of a sharpened stone

Now, discover all the grisly ways we’ve been beheading since then…

Beheading As Punishment

German soldiers behead a Yugoslavian partisan in March 1942.

Beheading has a long, varied history as a means of punishment.

From the very start, a class distinction was made between beheading with a sword, which is allegedly swift and merciful, and chopping with an ax, which certainly is not.

Aristocrats and other high-value prisoners were traditionally given the gentleman’s treatment with a single stroke of the sword. Peasants and outlaws — those who weren’t worth hanging, at least — were put on the block for a chop with an ax.

While not as terrifying as some of the worst methods of execution ever devised, beheading is fast and certain. It’s also efficient. As European nations grew in power, and as they sought to exert that power down to the street level in every town they controlled, beheading for even very minor crimes became routine.

By 1800, the so-called “Bloody Code” of England prescribed mandatory death sentences for over 200 crimes, including the theft of 12 pence, which had the purchasing power of just about $25 today.

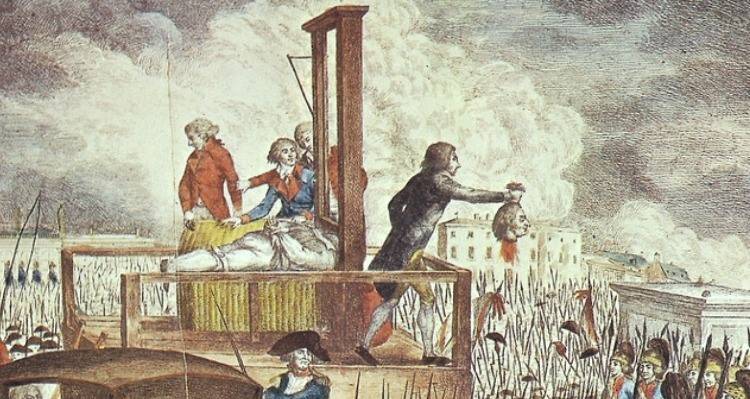

Beheading by guillotine. France, 1929. Image Source: Pinterest

In neighboring France, as the power of the monarchy weakened immediately prior to the revolution, the urge to crush perceived threats increased, leading to a major upswing in beheadings. To simplify the process, and to better manage panicky victims who wouldn’t hold still for the ax, Joseph-Ignace Guillotin urged the National Assembly to adopt the use of a new beheading machine, named after himself.

Between 16,000 and 40,000 French citizens — Marie Antoinette, nobles, clergy, and anyone suspected of being an enemy of the revolution — would be sentenced to “the National Razor” (more commonly known as the guillotine) between 1792 and 1794, the years of the Terror.

In time, the public spectacle declined, but the device remained in use until France’s last execution in 1977. The death penalty was abolished, and the guillotine with it, in 1981.

Today, no Western country permits decapitation as a legal punishment. Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Qatar, however, maintain beheading as an option. Of these countries, only Saudi Arabia routinely inflicts the punishment, with around 100 beheadings by scimitar per year.

Under Saudi law, people can be sentenced to death for adultery, blasphemy or apostasy (though the condemned have three days to recant), atheism, burglary, sodomy, fornication, sorcery, sedition, and “waging war on God.” Beheading is also imposed for murder, though wealthy killers are allowed to buy their way out of death, sometimes for millions of dollars paid to the victim’s family.

Beheading As A Wartime Weapon

This 1894 illustration depicts Japanese soldiers beheading Chinese captives during the First Sino-Japanese War. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

As enthusiastic as governments have always been about cutting off criminals’ heads, armies have been even more willing to behead captives.

Some of the earliest bas-reliefs depict all-powerful kings from Egypt and Assyria gathering up prisoners for decapitation. Heads have been taken as prizes in warfare since the invention of the sword, and few defeated armies throughout history have been spared.

In 1191, during the Crusades, Richard the Lionheart of England fought his way into control of the Muslim Saracen city of Acre, near Jerusalem. When subsequent negotiations with the Saracen leader, Saladin, hit an impasse, Richard showed he meant business by taking between 2,500 and 5,000 Muslim prisoners of war to the city’s walls and having their heads cut off in view of the enemy army. Negotiations resumed, and the Third Crusade ended with a mutually agreeable treaty.

After the Enlightenment, European societies got the idea that the gore and bloodshed of war was a grim duty, rather than a fun pastime, and the killing of captives declined. In the East, however, cutting off the heads of defeated enemies was still standard operating procedure until the 20th century.

The Japanese, who emerged from deep political isolation in the 1850s and immediately built up a modern colonial empire, put their traditional respect for the sword to the practical task of cleansing whole cities in occupied Korea during the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894-95. Beheading was later supplemented by the more efficient method of shooting, but slicing heads off of prisoners continued to the end of the Imperial period.

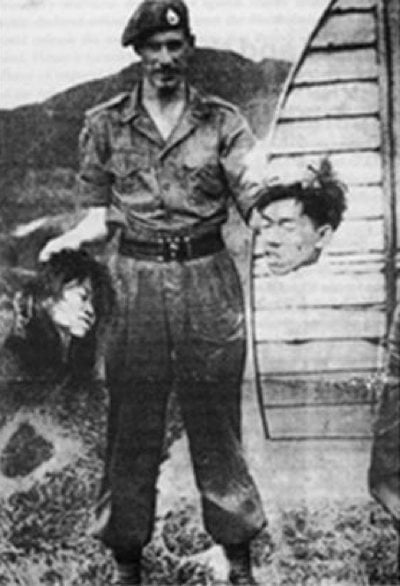

A British Royal Marine holding the severed heads of a young man and woman who were accused of supporting the Communist Party of Malaya in 1952.

Western armies may have officially stopped beheading captives in the 18th century, but that enlightened attitude didn’t always make it down to the troops (see above).

This type of violence is used for psychological effect by special operations forces around the world, such as the French Foreign Legion, which teaches its troops to leave decapitated enemy soldiers in the open for shock value.

Beheading As Propaganda

In Iraq, ISIS decapitates a person accused of being a homosexual.

The psychological impact of seeing a severed head — or, better yet, witnessing the act of beheading itself — is not lost on today’s terrorist groups.

ISIS has blazed a trail in this department. While its predecessor organizations, specifically Al Qaeda, always used beheading videos to intimidate opponents overseas, the Islamic State has turned the slow, gruesome sawing off of a captive’s head into a public spectacle.

Unlike the judicial beheading practiced with a sword in Saudi Arabia, ISIS beheadings are usually done with a short knife for maximum blood and gore. Ideally, the victim screams and begs for his life throughout the killing, maximizing its propaganda value.

In an echo of the region’s Assyrian past (made ironic by the Islamic State’s effort to erase the pre-Islamic history of Iraq), ISIS victims’ heads are often mounted on pikes and displayed in public as a deterrent and as a boast of the Caliphate’s power to kill Americans and other enemies.

This still from an ISIS beheading video released in early February shows a young boy threatening America while his prisoner kneels before him.

Cutting off the head of somebody you don’t like is such a simple, obvious way to kill that it will probably never fall completely out of use. While only three countries in the world currently allow beheading — and only one actually does it — the act of violently separating the heads of heretics, traitors, and enemy fighters will persist as long as such gory theater is felt to be necessary.

For more grizzly facets of human history, check out our other posts on the sordid history of defenestration and the eight most painful torture devices of the Middle Ages.