A pioneer in both physical therapy and forensics, Bessie Blount Griffin was best known for creating devices to help veteran amputees during World War II and teaching them to write with their teeth and feet.

Forced to leave school after the sixth grade, Bessie Blount Griffin nevertheless went on to become a nurse, an inventor, and a pioneer in both physical therapy and forensics.

A physical therapist, an inventor, a writer, and a forensic handwriting analyst, Bessie Blount Griffin got her start in a one-room segregated schoolhouse with no textbooks — and rose to greatness. During a time when there were few Black women working in science roles, Blount’s determined nature and knack for innovation helped her become a trailblazer in every field she entered.

She was the first Black woman to appear on The Big Idea, the 1950s television show about modern inventions, and the first woman of color to be accepted to pursue advanced studies at the Document Division of England’s Scotland Yard. She also was a founding member of the American Association of Handwriting Analysts and regularly wrote for many leading Black newspapers and magazines.

However, she’s perhaps best known for her work with amputee veterans, developing inventions and teaching them skills that would help them complete everyday tasks.

This is the story of Bessie Blount Griffin, the fierce and resourceful scientist who overcame all the obstacles put in her way — and made history.

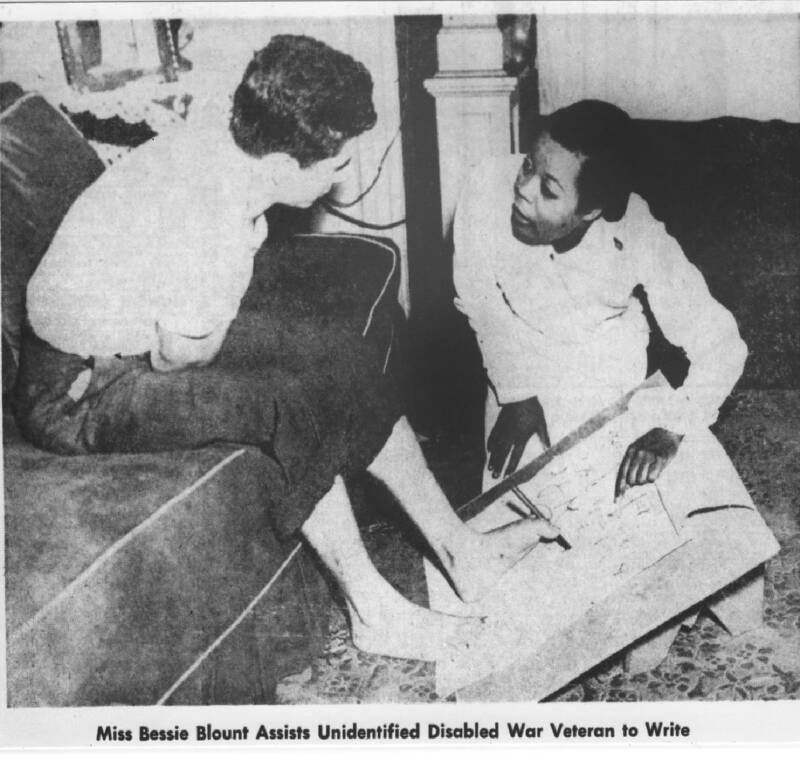

Bessie Blount Griffin FoundationBessie Blount Blount assisting an amputee as a post-war physical therapist.

Bessie Blount Griffin’s Early Life And First Physical Therapy Work

Bessie Blount Griffin was born on Nov. 24, 1914, in the community of Hickory, Virginia (present-day Chesapeake). Her education started in a one-room schoolhouse called Diggs Chapel Elementary School. According to the New York Times, the school was built by Black community members after the Civil War as a place to educate the children of formerly enslaved people.

It was here that Blount butted heads with a childhood teacher in an event that would help shape her entire future.

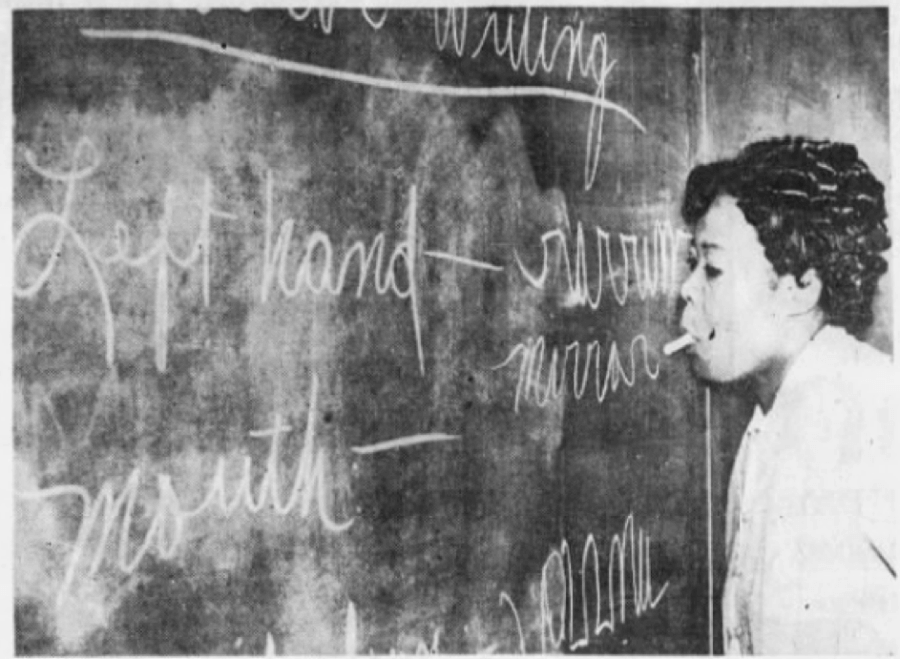

Blount was left-handed, something that was deemed unacceptable at the time. When her teacher caught her writing with her left hand, she reprimanded young Blount by rapping her knuckles. Stubborn and innovative even as a young girl, Blount countered this chastisement by teaching herself not only be to be ambidextrous, but to write by holding a pencil in her teeth. She also learned how to write with her feet.

“If it was wrong to write with my left hand, then it was wrong to write with my right hand,” she later said.

Smithsonian Magazine reports that there were no schools near Blount that offered higher education for Black students, so after completing all the formal schooling available to her in sixth grade, she made her own education plan.

After deciding she wanted to become a physical therapist, she achieved a rare honor at the time. Blount was accepted to Union Junior College and Panzer College of Physical Education and Hygiene. As a physical therapist, she went on to teach amputees returning from WWII how to do everyday tasks after they’d lost hands or feet on the battlefield. Crucial things like eating — but also writing.

And if there was one thing Bessie Blount Griffin could teach from firsthand experience, it was alternative ways to write. Soon, she was teaching patients how to write with their teeth and feet just as she had learned to do years before.

“You’re not crippled, only crippled in your mind,” she told them.

Soon, her work with disabled veterans would inspire her to make her first invention.

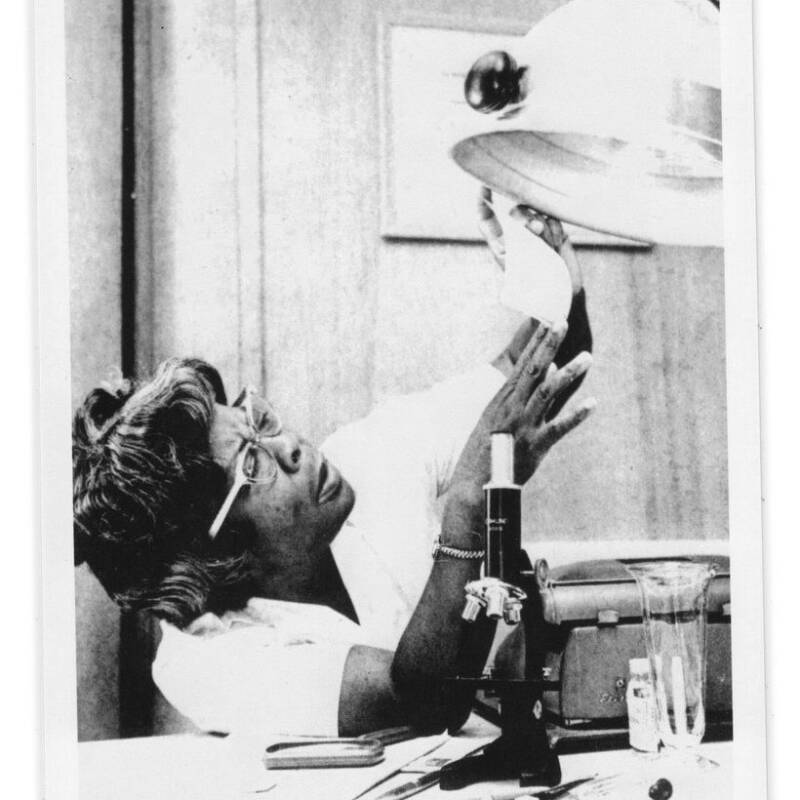

Access ETSU/FacebookScientist Bessie Blount Griffin at work.

Griffin’s Groundbreaking Inventions For Amputees

Bessie Blount Griffin became a licensed physiotherapist and taught amputees writing skills at Bronx Hospital (now Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center) in New York.

While there, she realized that the amputees could greatly benefit from a way to feed themselves without a caregiver. She came up with a design for an electronic feeding device that allowed a patient to bite down on a tube and have bites of food delivered to their mouths.

Blount worked on the prototype in her own kitchen, melting plastic using boiling water and employing everyday tools like files, hammers, an an ice pick to shape the device.

In 1951 she patented a portion of her design, a portable receptacle device that used a neck brace with built-in support to hold bowls or cups close to the mouth. She was excited to get it put to use. However, the Veterans Administration wanted nothing to do with Blount’s invention. Instead, she donated it to the French government so it could start helping people.

Blount also developed a disposable emesis basin to holds bodily fluids and waste, which would spare hospitals from having to clean out their basins after every use. She fashioned the prototype from a mixture of flour, water, and newspaper. The Veterans Administration, again, was not interested. She sold the idea to Belgium, and they still use a variation of it today.

According to her family, Blount never stopped inventing, but did stop applying for patents on her designs.

TwitterBessie Blount Griffin never stopped working in any of her science and medicine fields until the day she died.

Bessie Blount Griffin’s Second Career In Graphology

In the 1960s, Blount began a second career conducting forensic research for police departments in Vineland, New Jersey and Virginia. Her specialty became graphology, the analysis of handwriting to profile one’s behavior.

“I have been taught that a person’s signature is his ‘written’ fingerprints and [they] are just as valid as those on his fingers or the sole prints of his feet,” she wrote, according to A&E.

During the 1970s, Blount worked as the chief document examiner in Portsmouth, Virginia. Eventually, she ended up working at England’s Scotland Yard as a handwriting expert. She went on to specialize in detecting forged documents.

Bessie Blount Griffin continued to work as a consulting forensic analyst into her 80s. Even after she retired from law enforcement work, she still didn’t rest, but consulted with museums and researchers, determining the authenticity of pre-Civil War documents and letters related to the slave trade, as well as Native American treaties.

Once, Blount observed her 12-year-old grandson Nicholas’ handwriting and (correctly) gave him a diagnosis of weak vision in one eye.

“She said it was all in your writing, that your writing showed you how you were physically as well as mentally,” Nicholas Griffin said. “It’s a bit of science but it’s a bit of a gift — and that’s what she had as well.”

Bessie Blount Griffin died in 2009 at her home in Newfield, New Jersey. She was 95 years old.

After this look at Bessie Blount Griffin, read about another overlooked Black inventor, Garrett Morgan. Then, discover 33 facts about Black history you didn’t learn in school.