A medieval bestiary is a vibrantly illustrated compendium of both real and mythical animals — and the comically bizarre way scholars drew these beasts has baffled historians for centuries.

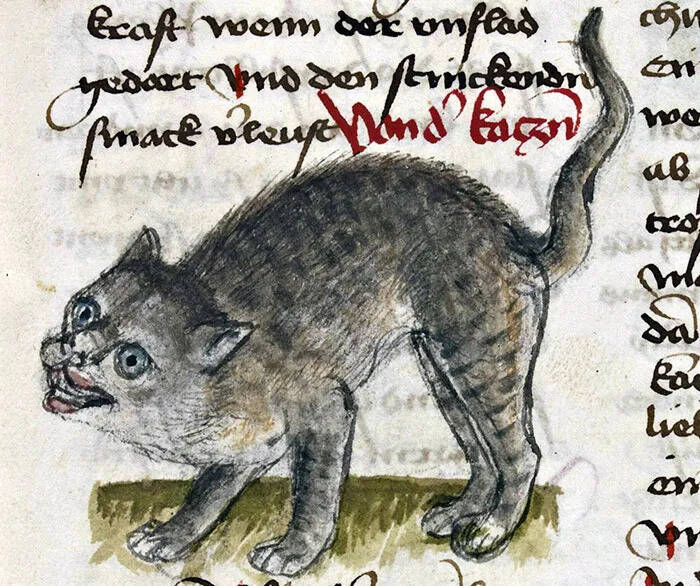

Public DomainA creepy 14th-century depiction of a domestic cat from Das Buch der Natur by Konrad de Megenberg.

During the Middle Ages, animals played essential roles in everything from agriculture to trade, transportation, and sustenance. Whether you were a farmer or a monarch, it’s likely animals were a part of your everyday life. It is no surprise, then, that medieval writers and artists often looked to animal imagery to help them connect with their audiences.

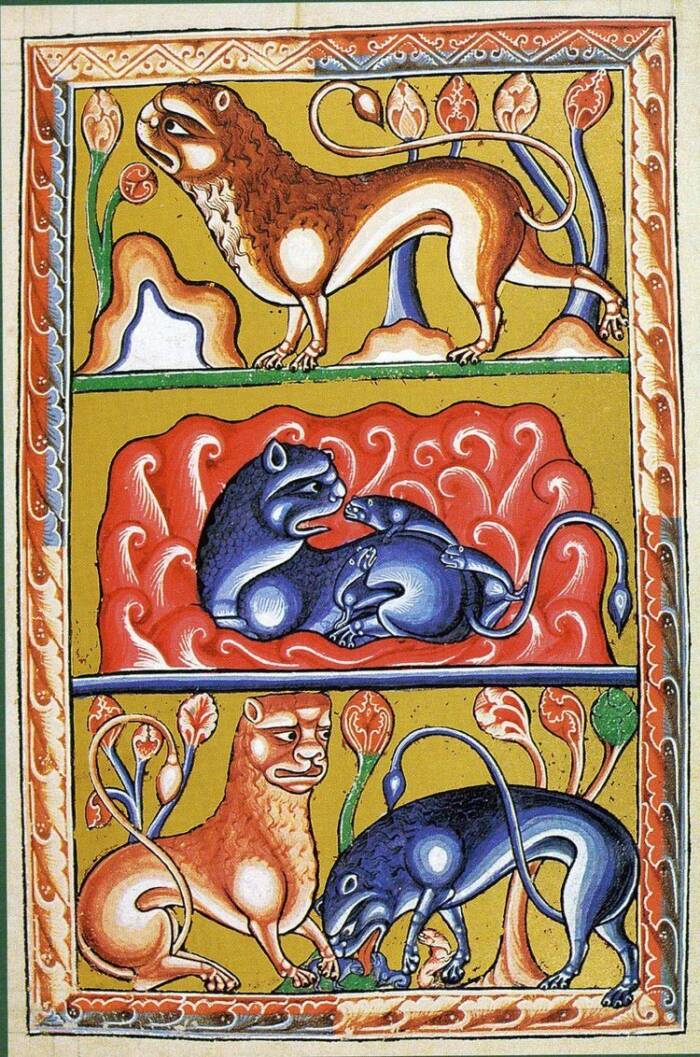

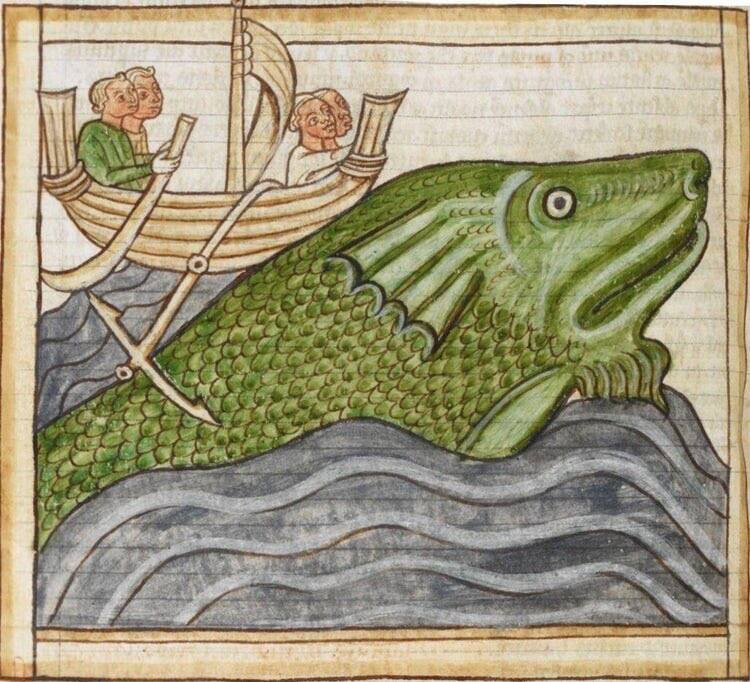

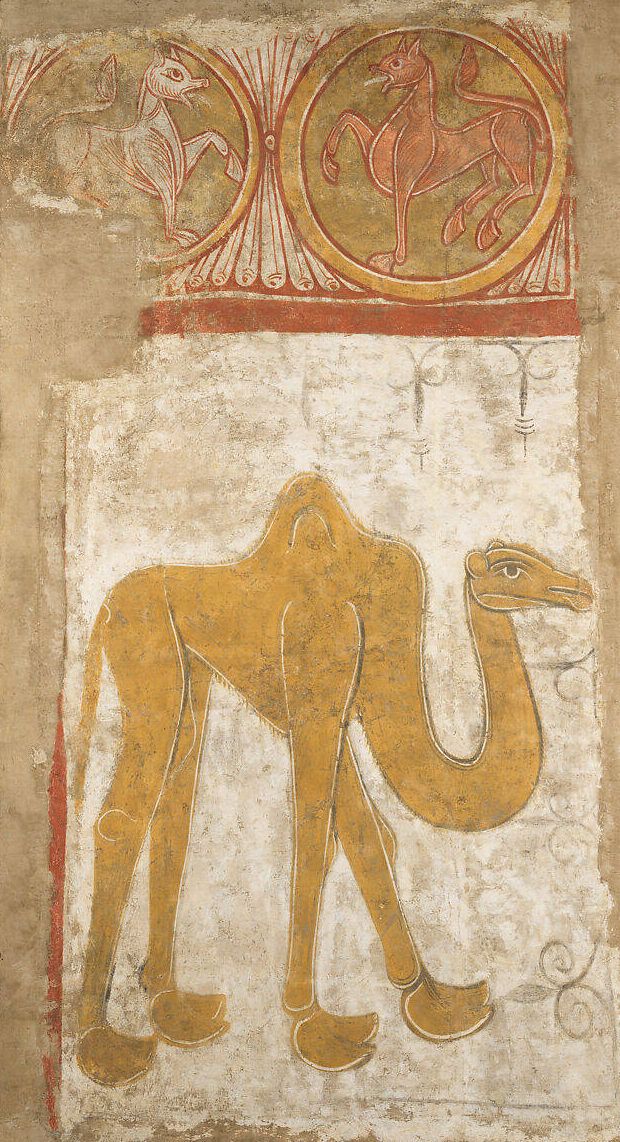

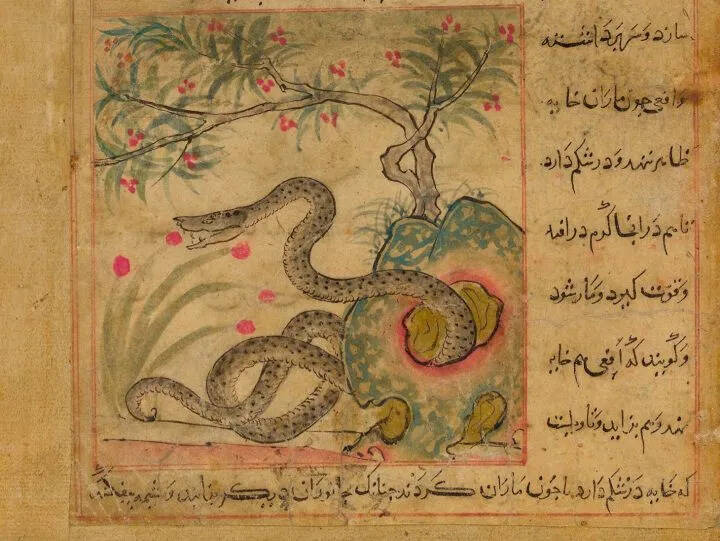

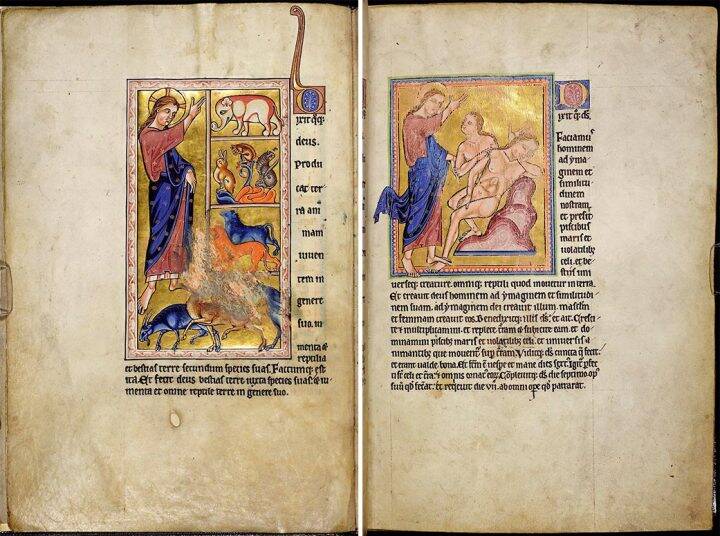

Throughout the Middle Ages, scholars created illuminated manuscripts called bestiaries — encyclopedias used to document various beasts’ natural history. These volumes contained lavish illustrations of both real and mythical beasts, often accompanied by moral and religious lessons. Today, however, these medieval animal compendiums are best known for their outlandish, fantastical, and sometimes hilarious depictions of animals.

Explore the strange world of medieval bestiaries by perusing the gallery below.

The Rise Of Medieval Bestiaries

Public DomainA page from the Aberdeen Bestiary, one of the most opulent of its time.

In the 2nd century C.E., unknown authors compiled a Christian encyclopedia of animals called the Physiologus, an illustrated book containing drawings and descriptions of various beasts. This early volume influenced countless medieval animal compendiums in the years that followed, which came to be known as "bestiaries."

In many of these texts, descriptions and illustrations of each animal were accompanied by moral lessons rooted in religious doctrine. The animals themselves often served as religious allegories, as scholars attributed different moral traits to various beasts and encouraged readers to find wonder and spiritual meaning in the natural world.

While bestiaries were originally used by religious institutions, and particularly to educate monks in monasteries, people of wealth and influence would sometimes commission these opulent manuscripts for their own study or entertainment.

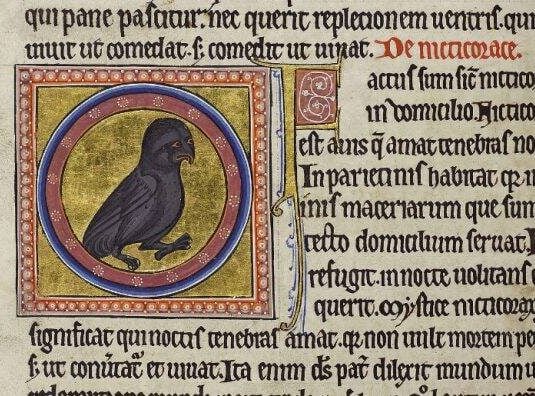

In fact, one of the most famous bestiaries, the Aberdeen Bestiary, was once owned by King Henry VIII. This 12th-century English illuminated volume features dozens of intricately painted animals on gold leaf backgrounds, including cattle, birds, fish, and even mythical creatures.

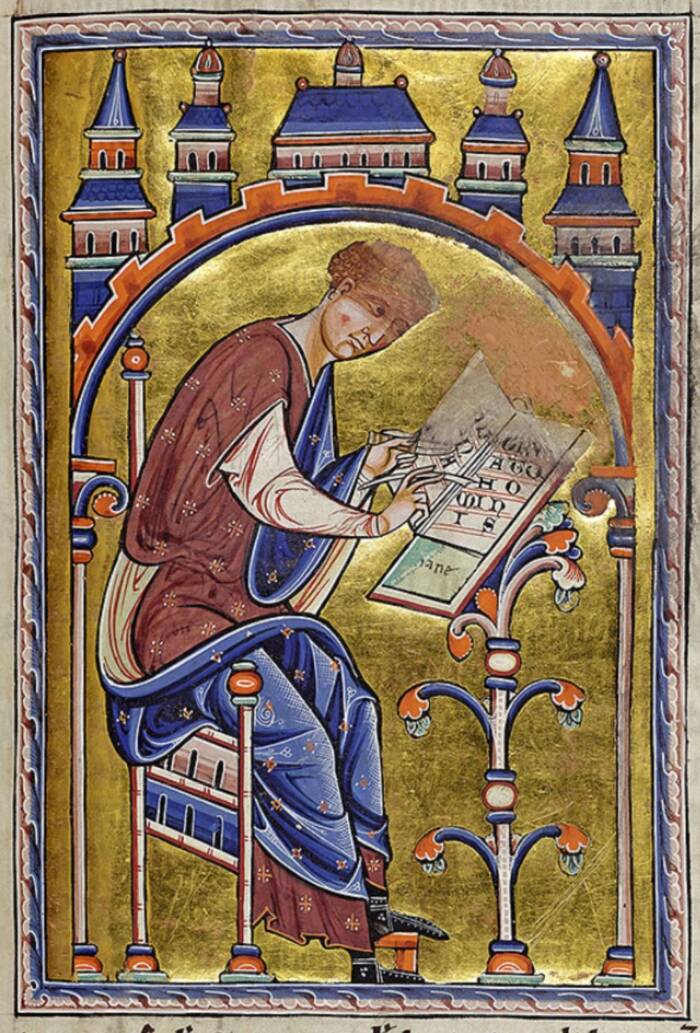

Public DomainIsidore of Seville writes his Etymologies, a text that included zoological descriptions of different animals.

Bestiaries' popularity exploded in the 12th and 13th centuries, particularly in France and England. Today, over 50 medieval bestiaries survive, most of which are highly ornamented and written in Latin.

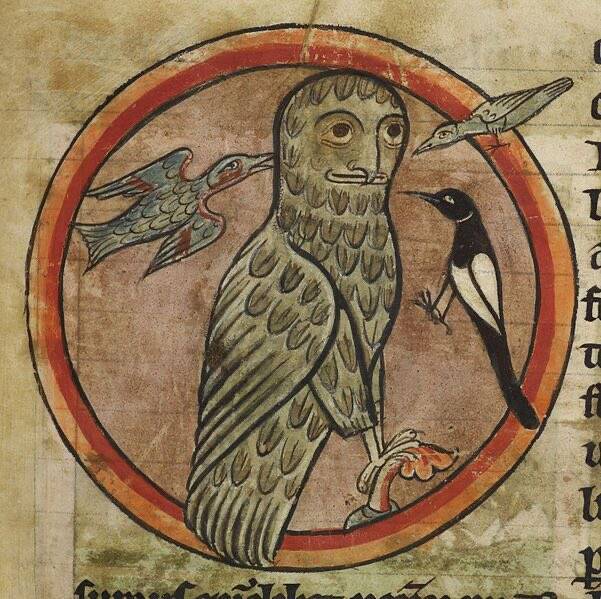

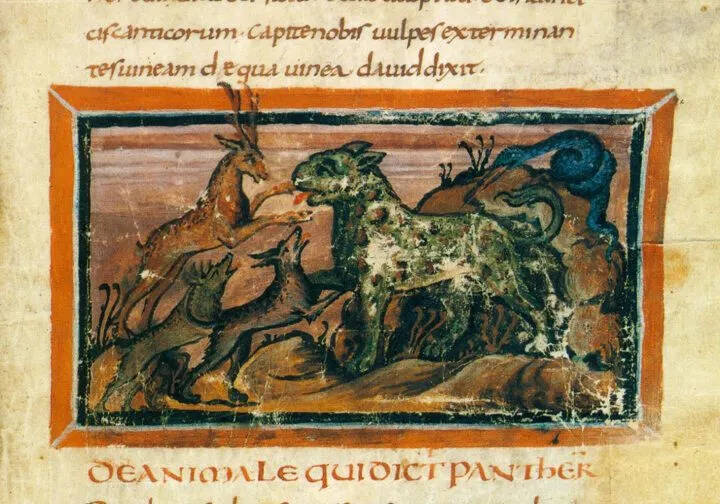

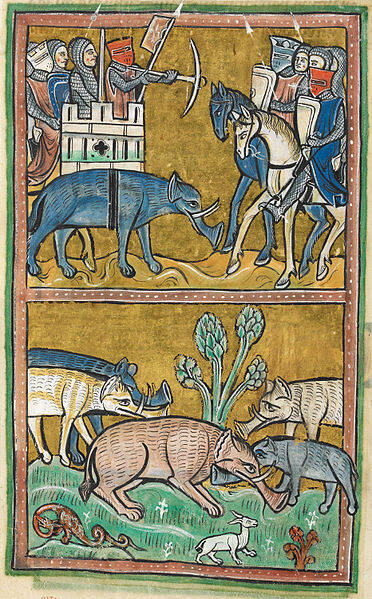

Interestingly, many bestiary authors did not distinguish between real and mythical animals when documenting them, prompting debate among historians as to whether medieval Europeans really believed in fantastical creatures, or viewed them purely as symbolic representations of moral ideals. Unicorns, for instance, might represent purity, while dragons were associated with Satan.

This debate has been furthered by bestiary authors' bizarre depictions of real animals, which often had fantastically exaggerated or humanlike appearances themselves.

So, why did medieval artists portray animals this way?

Why Do They Look Like That?

Public DomainA medieval drawing of a unicorn slaying, c. 1250 to 1260.

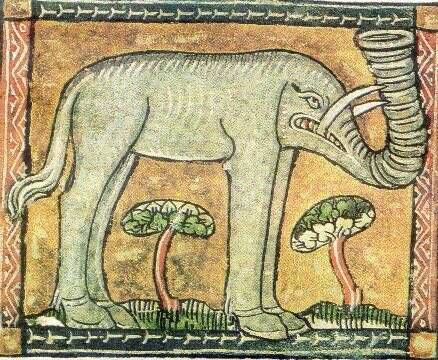

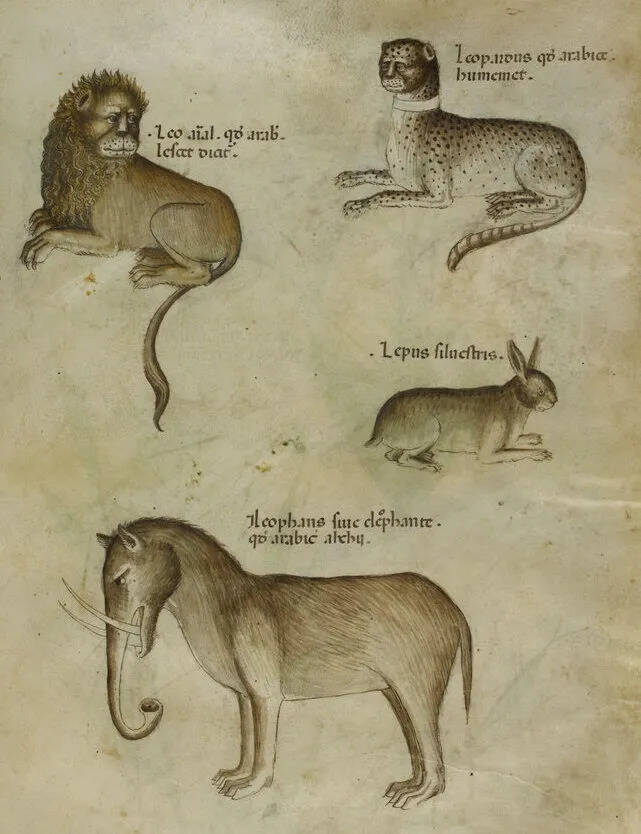

Today, medieval bestiaries are known for their comically bizarre depictions of animals, which were often drawn too big, too small, suspiciously human-like, or frankly unrecognizable. Dogs had eerily human faces, elephants had tornado trunks, and snails had furry ears and teeth.

At first, it may appear as if the artists were simply trying their best to depict exotic animals they had heard about but never seen before. However, many of these drawings feature animals that were commonplace in medieval Europe, such as cats and dogs.

Some scholars have theorized that the animals were purposefully drawn in outlandish ways to make them — and therefore any moral lesson accompanying them — more memorable.

"These books use animals to tell stories about theological concepts to make aspects of Christianity more accessible, easier to understand, and memorable," Larisa Grollemond, a curator at the Getty Museum, told Hyperallergic in 2023.

This theory could also explain why medieval bestiaries featured mythical creatures alongside real ones; if bestiaries were primarily meant to impart Christian lessons, it did not matter whether the creatures referenced were real or not.

"[Unicorns and dragons] are as plausible and as present in the imagination as an exotic animal like an elephant or a lion," Grollemond said. "There's not a distinction between something that we would call 'real' and then something that we would call 'imaginary.' They're all sort of on the same plane of existence."

The Memes Of The Medieval World

It's easy to poke fun at the bizarre, comically inaccurate illustrations found in bestiaries. But according to Shirin Fozi, associate curator at the Department of Medieval Art and The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Cloisters, these medieval animal drawings were actually meant to be humorous.

"Very often, people think that they're laughing at the Middle Ages, and they're actually laughing with the Middle Ages," Fozi told Hyperallergic. "The artist was trying to be funny."

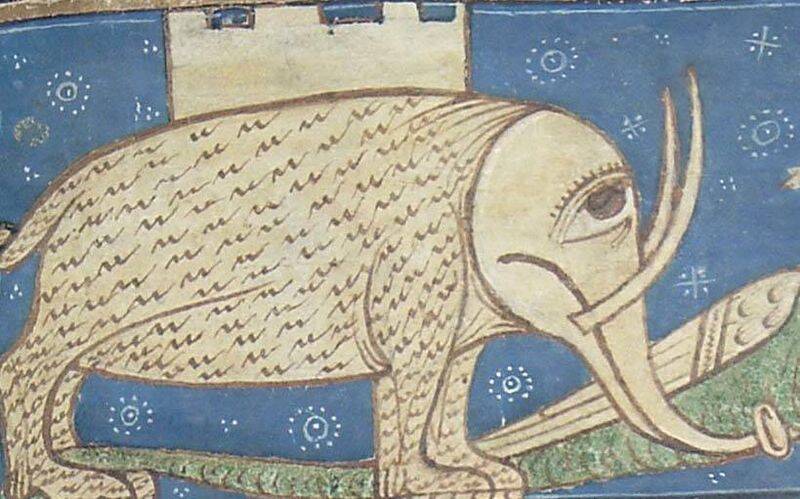

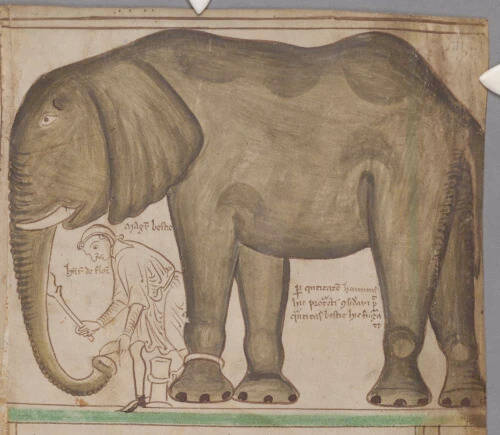

For example, Fozi explained, in Matthew Paris' 13th-century drawing of an elephant and its keeper, Paris accurately depicts the elephant, but deliberately gives the human keeper a cartoonish appearance.

Public DomainMatthew Paris' 13th-century drawing of an elephant and its keeper at the Tower of London.

"They already know what the elephant keeper looks like because he's just a normal guy," Fozi said. "We see the same artist working in different modes, whether he's trying to convey what the elephant looks like or whether he's just trying to tell a story."

Grollemond noted that many medieval readers would have found humor in these whimsical drawings.

"We still do this," Grollemond said. "With cat memes or whatever it is — we still find humor in animals all the time."

While they may seem silly, these animal illustrations offer a fascinating insight into medieval European society. For most of the Middle Ages, artists were simply tradespeople, rather than revered figures as they often were in antiquity. As such, it makes sense that the drawings would be a bit irreverent.

"People might ask why they couldn't draw animals right or why certain things look weird, but I think that's a reductive way of looking at it," Olivia Swarthout, data scientist and author of Weird Medieval Guys: How to Live, Laugh, Love (and Die) in Dark Times, told The Guardian in 2023.

"There's so much contained in this art — and particularly in the fact that a lot of it isn't all that well-executed or approached with the artistic precision that we're familiar with — that actually tells us so much about medieval life."

After reading about medieval bestiaries, dive into the stories of 29 of the world's most fascinating animals. Then, learn about the history of Ireland's stunning Book of Kells.