In Scandinavian legend, Björn Ironside was the son of Viking chieftain Ragnar Lothbrok who led successful raids across Europe in the ninth century C.E. before becoming a ruler of Sweden and Norway and founding the royal Munsö Dynasty.

History ChannelAlexander Ludwig portrays Björn Ironside in the History Channel show Vikings.

Of all the esteemed warriors in Viking history, few reached the renown of Björn Ironside. Like his father, Ragnar Lothbrok, Björn appears frequently in old Viking legends and Scandinavian histories — but that also makes it difficult to parse the truth about him from the myth.

Still, the similarities in all these accounts provide a fairly well-rounded description of Björn Ironside. He is most often described as a powerful and fearsome warrior with sides, as his name would suggest, like iron. He was known for the various expeditions he and his brothers — Ivar the Boneless, Hvitserk, and Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye — embarked upon, particularly a Mediterranean voyage during the late ninth century.

Their exploits have been popularized in more recent years thanks to the History Channel television series Vikings, but the show also contributes further to the blurred line between fact and fiction. Most of Björn’s exploits were shared in the 13th-century text The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok and the later work The Tale of Ragnar’s Sons, which chronicles the lives of Björn and his brothers after their father’s death.

So, who was Björn Ironside, really? It’s difficult to say, but what is clear is that the chronicles of his exploits have entranced readers for centuries.

Historical Accounts About Viking Warrior Björn Ironside

The first mentions of Björn in medieval sources are contested, and there are debates about whether they refer to the same person that’s recorded in later Scandinavian histories. However, they are still worth mentioning, as they offer the earliest evidence of Björn Ironside’s existence.

The Annales Bertiniani and the Chronicon Fontanellense reference a Viking chieftain named “Berno” who emerged as a formidable force in West Francia during the mid-ninth century.

In the summer of 856, Berno, alongside another Viking leader named Sigtrygg, sailed up the Seine River, launching raids. Their combined forces faced King Charles the Bald south of Paris that same year. Although they suffered a defeat, it wasn’t decisive.

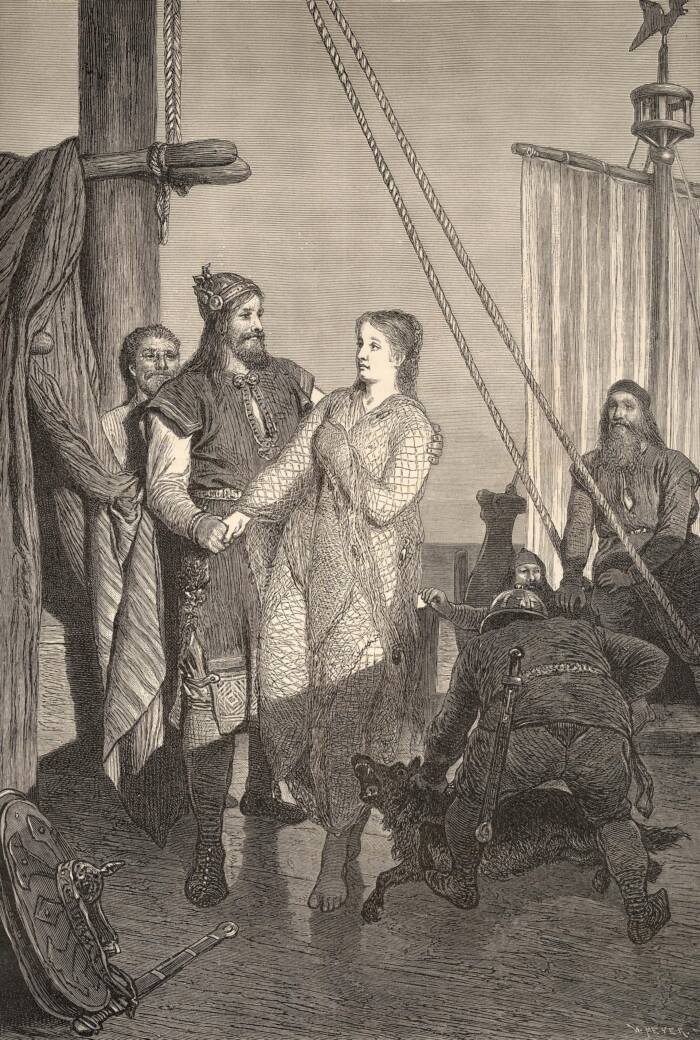

Public DomainRagnar Lothbrok with his wife Aslaug, the mother of Björn Ironside.

Sigtrygg withdrew in 856, but Berno fortified his position, receiving reinforcements and establishing a stronghold on the island of Oissel near Rouen. From this base, he launched a significant assault on Paris around the turn of 856 and 857.

Berno met with Charles the Bald to pledge fealty to him in 858, and later that year, the king ordered a raid against Oissel. However, since Berno’s name isn’t mentioned in contemporary records about the attack, it seems likely that he maintained his loyalty to the ruler and wasn’t involved in defending the island stronghold.

Another historical text, the 13th-century Gesta Danorum (“Deeds of the Danes”) by the Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus, speaks in greater detail about Björn and his family — and mentions that Björn Ironside even became a legendary king of Sweden.

The Accomplishments Of The Legendary Viking Leader As Detailed In ‘Gesta Danorum’

In Gesta Danorum, Sexo Grammaticus describes a conflict between Ragnar Lothbrok and Sörle, a newly appointed ruler of the Swedes. To resolve their dispute, both parties agreed to a combat involving select champions.

Ragnar, accompanied by his sons Björn, Fridleif, and Ragbard, faced the renowned warrior Starkad and his seven sons.

“Björn, having inflicted great slaughter on the foe without hurt to himself, gained from the strength of his sides, which were like iron, a perpetual name (Ironsides),” Sexo Grammaticus wrote. “This victory emboldened Ragnar to hope that he could overcome any peril, and he attacked and slew Sörle with the entire forces he was leading. He presented Björn with the lordship of Sweden for his conspicuous bravery and service.”

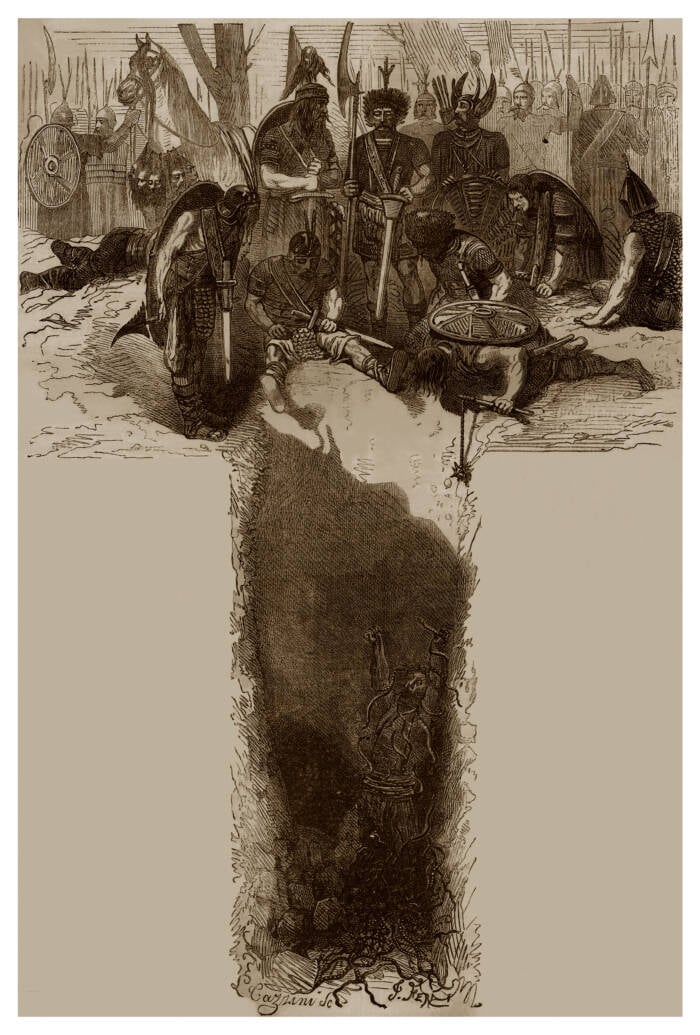

Public DomainRagnar Lothbrok’s sons meeting with King Ælla’s messengers.

Later, another of Ragnar’s sons, Ubba, conspired against his father. Ubba sent envoys to Sweden to gain support for a rebellion, but Björn refused to participate. According to Saxo Grammaticus, “Björn said that he would never lean more to treachery than to good faith, and judged that it would be a most abominable thing to prefer the favor of an infamous brother to the love of a most righteous father.”

Ragnar Lothbrok subsequently appointed Björn as the leader of Norway as well.

Then, as the legend goes, after Ragnar’s death in 865 at the hands of King Ælla of England, Björn and his brothers launched an assault to avenge his murder. They killed the king using the blood eagle method — a type of torture and execution typically believed to be fictitious.

Saxo Grammaticus wrote, “[W]hen they had captured him, they ordered the figure of an eagle to be cut in his back, rejoicing to crush their most ruthless foe by marking him with the cruelest of birds. Not satisfied with imprinting a wound on him, they salted the mangled flesh. Thus Ælla was done to death, and Björn and [his brother] Sigurd went back to their own kingdoms.”

Yolanda Perera Sánchez / Alamy Stock PhotoThe death of Ragnar Lothbrok after being thrown into a snake pit.

It’s worth noting that Saxo Grammaticus wrote his account several centuries after the subject of his tale walked the Earth — and that much of what he wrote aligns with accounts found in The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok and The Tale of Ragnar’s Sons, though certain details, like the name of Björn Ironside’s mother, differ.

The trouble is that the sagas are more widely believed to be fiction based on various warriors from the ninth century. These similarities, then, also cast some doubt on the accuracy of Saxo Grammaticus’ account.

‘The Saga Of Ragnar Lothbrok’ And ‘The Tale Of Ragnar’s Sons’

Public DomainAn 1880 edition of The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok.

In The Saga of Ragnar Lothbrok, Björn is portrayed as one of the sons of Ragnar and Aslaug — not Thora, as in Gesta Danorum — alongside his brothers Ivar the Boneless, Hvitserk, and Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye.

The saga tells of their collective quest to expand their kingdom, including the conquest of territories like Zealand, Jutland, Gotland, and Öland. Following these conquests, they establish their stronghold in Lejre, Denmark, with Ivar assuming leadership.

It also describes Ragnar’s ill-fated expedition to England, during which he boasted that he could invade the country with just two ships. This hubris resulted in his capture and death in a snake pit at the hands of King Ælla.

The Tale of Ragnar’s Sons effectively picks up there, expanding, as the title suggests, on the further exploits of Ragnar’s children following his death.

Like in Gesta Danorum, Björn and his brothers launched an initial assault against Ælla but faced setbacks. Ivar, ever the strategist, negotiated for land, which he cleverly used to establish a foothold. This move paved the way for a renewed attack, during which they captured Ælla and exacted vengeance through the blood eagle.

Björn and his brothers then embarked on extensive raids across England, Normandy, France, and Lombardy, eventually leading them to the city of Luni, the furthest they managed to reach. Realizing it would be too difficult to take the city, they returned to Scandinavia, where they divided their father’s kingdom. Björn received Uppsala in central Sweden and its surrounding lands.

Public DomainThe purported barrow, or burial mound, of Björn Ironside in Sweden.

Once again, Björn disappears from the record here, with no further mention of his exploits or his death. However, he also appears in another work from the 11th century by William of Jumièges.

This chronicle, Gesta Normannorum Ducum (“Deeds of the Norman Dukes”), tells of Björn Ironside’s exploits in the Mediterranean and links him with another Viking named Hastein. However, the account of William of Jumièges has also been widely criticized as being unreliable.

What’s more, Björn is said to have been the first leader of the Munsö Dynasty, a Swedish royal family that ruled during the Viking Age. Some experts believe this entire dynasty is legendary, as well, though.

The only other noteworthy chronicle of Björn Ironside’s life is, frankly, the Vikings television show — so how does it compare to the other accounts?

How Accurate Is The Portrayal Of Björn Ironside In Vikings?

History ChannelAlexander Ludwig and Katheryn Winnick as Björn and Lagertha in Vikings.

As far as Vikings is concerned, historical accuracy is not a priority. While many elements of the show — such as costuming — do capture a fair portrayal of the Viking Age, its timeline differs from historical texts.

The first major inconsistency is, once again, the name of Björn’s mother. In the show, she is known as Lagertha.

The series also condenses timelines, attributing various exploits to Björn that span different periods. For instance, his Mediterranean expedition is depicted alongside events that, historically or mythologically, occurred separately.

And naturally, given that it is a television drama, much of Björn’s growth as a character is entirely fabricated. Based on any historical accounts or legends, it would effectively be impossible to understand Björn’s psychology — and the idea of a “character arc” itself is pretty much exclusive to fiction.

Still, to be fair to the show, the actual history is also rather elusive.

After reading about Björn Ironside, learn about nine of history’s most brutal warlords. Or, see the surprising truth about Viking helmets — and how they look different than you might expect.