The 1921 Tulsa Massacre left hundreds dead and caused over $1.5 million in damage while the city's famed "Black Wall Street" was destroyed — in just 24 hours.

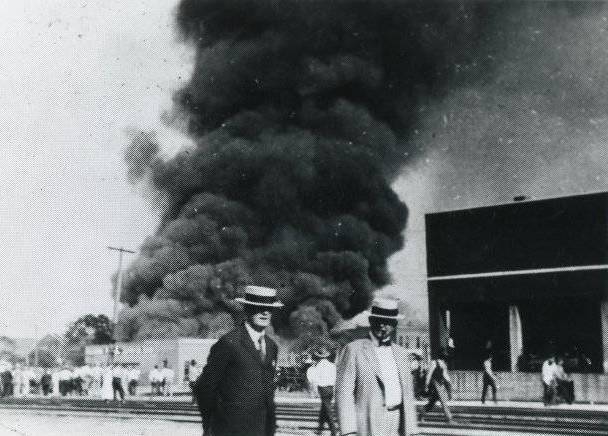

Wikimedia CommonsSmoke rises over “Black Wall Street” during the Tulsa Race Massacre.

Almost 100 years ago, in a small office building in Tulsa, Oklahoma, a man named Dick Rowland tripped on his way into an elevator. The car hadn’t stopped properly and Rowland hadn’t noticed, catching his foot on the uneven ledge. As he fell, he reached out, looking for something to stop him. That something turned out to be someone — Sarah Page, the young elevator operator, who naturally screamed as a man fell on top of her.

In another place, at another time, between anyone else, the incident may have gone unnoticed. But the place was Greenwood, Oklahoma — then known as “Black Wall Street.” The time was 1921. And Dick Rowland was a Black man. To make matters worse, Sarah Page was a white woman.

Onlookers who witnessed the mishap immediately called it “rape,” upon seeing a 19-year-old Black male shoeshiner grasping an elevator attendant who was a 17-year-old white female. The police were immediately called.

Despite Rowland’s insistence that he had simply tripped on his way to use the segregated restroom, he was arrested. An article, published astonishingly fast in the town’s newspaper, called for Rowland’s lynching.

In response, hundreds of people showed up to the courthouse. A small number of them were Black residents showing up to protect Rowland. A much larger number were a white mob, anxious to fulfill the newspaper’s request.

Before long, the Black residents were forced to stand down, as the most brutal and destructive race massacre in American history unfolded. Within mere days, the Tulsa Race Massacre saw Black Wall Street burned to the ground.

What Was Black Wall Street?

Tulsa Star/FlickrThe Red Wing Hotel in Greenwood, pictured circa 1918. This hotel would later be destroyed in the Tulsa Race Massacre.

The neighborhood, called Greenwood, was known as “Black Wall Street” due to the prominent Black entrepreneurs that resided there and the successful businesses they owned. The neighborhood had begun to thrive on Black customers and salespeople alone, a first for a town at that time.

Founded in 1906, Greenwood was built on what was originally Indian Territory. Some African Americans who used to be slaves of tribes were finally able to integrate into tribal communities and even acquire some land in the process. O.W. Gurley — a wealthy Black landowner — was the one who purchased 40 acres of land in Tulsa and named it Greenwood.

“Gurley is credited with having the first black business in Greenwood in 1906,” explained Hannibal Johnson, author of Black Wall Street: From Riot to Renaissance in Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District, in an interview with The History Channel. “He had a vision to create something for black people by black people.”

Gurley started out small with a boarding house for African Americans. But then, he began to loan out money to other Black people who wanted to start businesses — giving them opportunities they may not have had elsewhere.

Tulsa Star/FlickrAn ad for Caver’s French Laundry, a laundry and tailor business in pre-massacre Greenwood.

Understandably, other Black entrepreneurs were attracted to a place like this. For instance, former slave J.B. Stradford — who later became a lawyer — moved to Greenwood and built a luxury hotel there, bearing his name.

“Oklahoma begins to be promoted as a safe haven for African Americans who start to come particularly post emancipation to Indian Territory,” explained Michelle Place, executive director of the Tulsa Historical Society and Museum.

Unfortunately, this “safe haven” wouldn’t last.

It didn’t take long for white people to notice the prosperous community of Greenwood. And needless to say, they weren’t exactly happy about it.

“I think the word jealousy is certainly appropriate during this time,” said Place. “If you have particularly poor whites who are looking at this prosperous community who have large homes, fine furniture, crystals, china, linens, etc., the reaction is ‘they don’t deserve that.'”

Arguably, this widespread resentment brewing under the surface set the scene for making the Tulsa Race Massacre all the more destructive.

The Brutality Of The Tulsa Race Massacre

Wikimedia CommonsSmoke filled the skies above the Black residential areas of Tulsa throughout the massacre.

Over the course of 12 hours, a white mob, joined by more rioters, collectively burned down almost all of Black Wall Street. They looted businesses, shot and attacked Black residents, and left the town in ruins.

Before long, Oklahoma’s governor had declared martial law, bringing in the National Guard to end the violence. Some say the police and the Guard joined the fights, dropping sticks of dynamite from planes and firing machine guns into swarms of Black residents.

A recently resurfaced eyewitness account from Oklahoma lawyer Buck Colbert Franklin detailed the chaos:

“I could see planes circling in mid-air. They grew in number and hummed, darted and dipped low. I could hear something like hail falling upon the top of my office building. Down East Archer, I saw the old Mid-Way hotel on fire, burning from its top, and then another and another and another building began to burn from their top.”

He continued: “Lurid flames roared and belched and licked their forked tongues into the air. Smoke ascended the sky in thick, Black volumes and amid it all, the planes—now a dozen or more in number—still hummed and darted here and there with the agility of natural birds of the air.”

Franklin writes that he left his office and locked the door before taking a closer look at the terrifying scene unfolding outside.

“The side-walks were literally covered with burning turpentine balls. I knew all too well where they came from, and I knew all too well why every burning building first caught from the top. I paused and waited for an opportune time to escape. ‘Where oh where is our splendid fire department with its half dozen stations?’ I asked myself. ‘Is the city in conspiracy with the mob?'”

Wikimedia CommonsA group of men watches the fire from a distance.

Twenty-four hours later, it was over, but the damage had already been done.

According to initial reports, more than 800 people were injured, and roughly 35 had died. More recently, in 2001, an investigation by the Tulsa Race Riot Commission claimed the death toll was closer to 300.

Over 35 blocks of city streets had been burned, resulting in more than $1.5 million in property damage. Today, that would be roughly $30 million.

10,000 Black residents had been left homeless, and over 6,000 were held by the National Guard, some for as long as eight days.

Within days of the Tulsa Race Massacre, the Black community began the long and extremely difficult process of rebuilding Greenwood. Thousands were forced to spend the winter of 1921 and 1922 living in flimsy tents.

While Greenwood was eventually rebuilt, many families never fully recovered from the violence.

What Happened To Dick Rowland?

Despite Dick Rowland being a central figure in this story, very little is known for certain about him — or his life after the Tulsa Race Massacre. (Sometimes, even his name is disputed, as it’s occasionally spelled Dick “Roland” instead of Rowland.)

What we do know from the Oklahoma Commission’s report on the massacre is that the case against Dick Rowland was eventually dismissed in September 1921. We also know that Sarah Page (the white woman in the elevator) did not appear as a complaining witness against Rowland in court — perhaps a big reason as to why the case was dismissed.

As to what happened to Dick Rowland after he was exonerated, that still remains a mystery. Some sources claim that after his release, he immediately left Tulsa for Kansas City. There were also rumors that he moved even further north than that.

However, experts have been unable to verify exactly where Dick Rowland went after his release. The precise date of his death also remains unknown.

Considering the massive violence that had just unfolded in Greenwood — and the fact that an angry white mob had wanted to lynch him — it would not be surprising if Rowland left the area as soon as he possibly could.

Plus, even though Rowland was exonerated, an all-white grand jury would later blame Black Tulsans for the lawlessness in a series of recriminations and legal maneuvering.

Despite heaps of evidence, no white people were ever sent to prison for the murders or arson of the massacre.

How Black Wall Street Is Remembered Today

Wikimedia CommonsThe National Guard tending to the wounded.

Despite being the worst instance of racial violence in Oklahoma’s history (some say the world), the Tulsa Massacre was all but erased from national memory for decades.

But in 1971, that started to change. Impact Magazine editor Don Ross published one of the first accounts of the massacre, nearly 50 years after it happened. He later went on to become a state representative. According to NPR, Ross and State Senator Maxine Horner are often credited with bringing national attention to this forgotten part of history.

Still, a state commission wouldn’t be formed until 1997 to investigate the violence that took place in Greenwood all those years ago. And in 2001, the commission’s report recommended that survivors be paid reparations. The Oklahoma state legislature refused.

Even though the survivors didn’t win reparations, organizations such as the Tulsa Historical Society, the Greenwood Cultural Center, and the University of Tulsa are working toward new goals: raising awareness of the massacre’s existence and educating Americans about its historical significance.

Most notably, activists are pushing for the Tulsa Massacre to be covered more extensively in history textbooks. Shockingly, the incident was not part of the Oklahoma public schools’ curriculum until 2000, and mention of the event was only recently added to more general American history books.

Perhaps more mentions in the media will also make a difference. For instance, the massacre was recently depicted in the HBO series “Watchmen.”

One thing’s for sure: This crucial piece of history was forgotten far too long. It’s up to future generations to make sure it is never forgotten again.

Now that you’ve read about Black Wall Street, take a look at the most horrifying photos from the Tulsa Race Massacre. Then learn about more of the worst riots in history.