Bobby Fischer became the World Chess Champion after defeating Soviet Boris Spassky in 1972 — then he descended into madness.

In 1972, the U.S. seemed to have found an unlikely weapon in its Cold War struggle against Soviet Russia: a teen chess champion named Bobby Fischer. Though he would be celebrated for decades to come as a chess champ, Bobby Fischer later died in relative obscurity following a descent into mental instability.

But in 1972, he was at the center of the world stage. The U.S.S.R. had dominated the Chess World Championship since 1948. It saw its unbroken record as proof of the Soviet Union’s intellectual superiority over the West. But in 1972, Fischer would unseat the USSR’s greatest chess master, reigning world chess champion Boris Spassky.

Some say there has never been a chess player as great as Bobby Fischer. To this day, his games are scrutinized and studied. He has been likened to a computer with no noticeable weaknesses, or, as one Russian grandmaster described him, as “an Achilles without an Achilles heel.”

Despite his legendary status in the annals of chess history, Fischer expressed an erratic and disturbing inner life. It seemed as if Bobby Fischer’s mind was every bit as fragile as it was brilliant.

The world would watch as its greatest chess genius played out every paranoid delusion in his mind.

Bobby Fischer’s Unorthodox Beginnings

Photo by Jacob SUTTON/Gamma-Rapho via Getty ImagesRégina Fischer, Bobby Fischer’s mother, protesting in 1977.

Both Fischer’s genius and mental disturbance can be traced to his childhood. Born in 1943, he was the progeny of two incredibly intelligent people.

His mother, Regina Fischer, was Jewish, fluent in six languages and had a Ph.D. in medicine. It’s believed Bobby Fischer was the result of an affair between his mother — who had been married to Hans-Gerhardt Fischer at the time of his birth — and a notable Jewish Hungarian scientist named Paul Nemenyi.

Nemenyi wrote a major textbook on mechanics and for a time even worked with Albert Einstein’s son, Hans-Albert Einstein, in his hydrology lab at the University of Iowa.

Pustan’s then-husband, Hans-Gerhardt Fischer, was listed on Bobby Fischer’s birth certificate even though he’d been denied entry into the United States on account of his German citizenship. It’s believed that while he was away during this time, Pustan and Nemenyi likely conceived Bobby Fischer.

While Nemenyi was brilliant, he also had mental health issues. According to Fischer’s biographer Dr. Joseph Ponterotto, “there’s [also] some correlation between the neurological functioning in creative genius and in mental illness. It’s not a direct correlation or a cause and effect…but some of the same neurotransmitters are involved.”

Pustan and Fischer became estranged in 1945. Pustan was forced to raise both her newborn son and her daughter, Joan Fischer, alone.

Bobby Fischer: Chess Prodigy

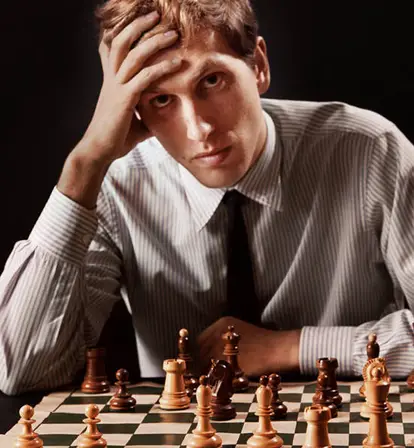

Bettmann/Getty Images13-year-old Bobby Fischer playing 21 chess games at once. Brooklyn, New York. March 31, 1956.

Bobby Fischer’s filial dysfunction did not hamper his love for chess. While growing up in Brooklyn, Fischer started to play the game by six. His natural ability and unshakeable focus eventually brought him to his first tournament at just nine. He was a regular in New York’s chess clubs by 11.

His life was chess. Fischer was determined to become a world chess champion. As his childhood friend Allen Kaufman described him:

“Bobby was a chess sponge. He would walk into a room where there were chess players and he’d sweep around and he’d look for any chess books or magazines and he’d sit down and he would just swallow them one after another. And he’d memorize everything.”

Bobby Fischer quickly dominated U.S. chess. By the age of 13, he became the U.S. Junior Chess champion and played against the best chess players in the United States in the U.S. Open Chess Championship that same year.

It was his stunning game against International Master Donald Byrne that first marked Fischer as one of the greats. Fischer won the match by sacrificing his queen to mount an onslaught against Byrne, a win lauded as one of “the finest on record in the history of chess prodigies.”

His rise through the ranks continued. At age 14, he became the youngest U.S. Champion in history. And at age 15, Fischer cemented himself as the chess world’s greatest prodigy by becoming the youngest chess grandmaster in history.

Bobby Fischer was the best America had to offer and now, he would have to go up against the best other countries had to offer, especially the grandmasters of the U.S.S.R.

Fighting The Cold War On The Chessboard

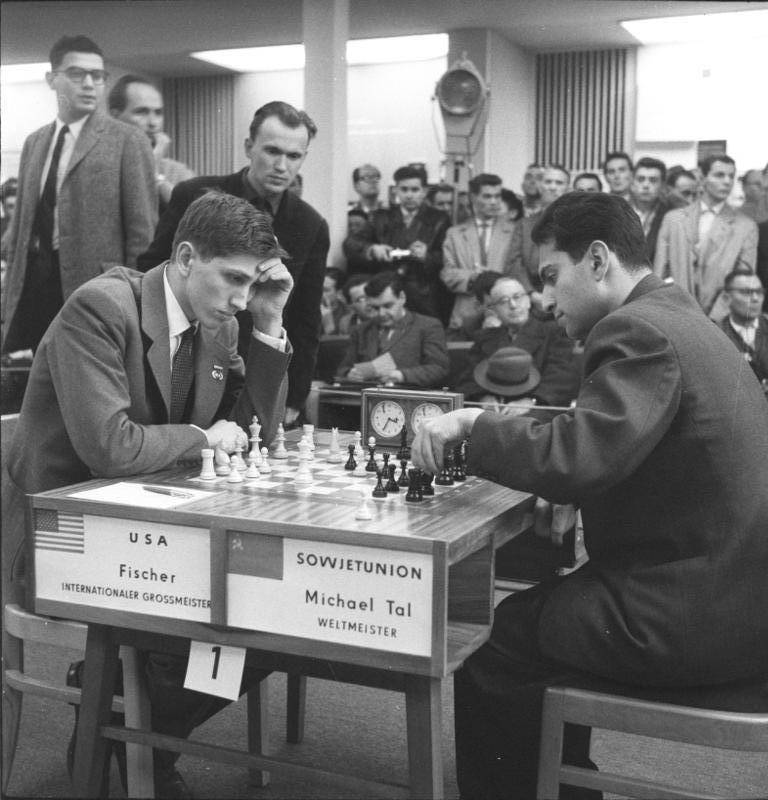

Wikimedia Commons16-year-old Bobby Fischer goes head-to-head with U.S.S.R. chess champion Mikhail Tal. Nov. 1, 1960.

The stage — or the board — was now set for Bobby Fischer to face off against the Soviets who were some of the best chess players in the world. In 1958, his mother, who always supported her son’s efforts, wrote directly to Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who then invited Fischer to compete in the World Youth and Student Festival.

But Fischer’s invitation arrived too late for the event and his mother could not afford tickets. However, Fischer’s wish to play there was granted the following year, when producers of the game show I’ve Got A Secret gave him two round-trip tickets to Russia.

In Moscow, Fischer demanded that he be taken to the Central Chess Club where he faced two of the U.S.S.R.’s young masters and beat them in every game. Fischer, though, wasn’t satisfied with just beating people his own age. He had his eyes on a bigger prize. He wanted to take on the World Champion, Mikhail Botvinnik.

Fischer flew into a rage when the Soviets turned him down. It was the first time Fischer would publicly attack someone for rejecting his demands — but by no means the last. In front of his hosts, he declared in English that he was fed up “with these Russian pigs.”

This comment was compounded after the Soviets intercepted a postcard he wrote with the words “I don’t like Russian hospitality and the people themselves” en route to a contact in New York. He was denied an extended visa to the country.

The battle lines between Bobby Fischer and the Soviet Union had been drawn.

Raymond Bravo Prats/Wikimedia CommonsBobby Fischer tackles a Cuban chess champion.

Bobby Fischer dropped out of Erasmus High School at the age of 16 to concentrate on chess full time. Anything else was a distraction to him. When his own mother moved out of the apartment to pursue medical training in Washington D.C., Fischer made it clear to her that he was happier without her.

“She and I just don’t see eye to eye together,” Fischer said in an interview a couple of years later. “She keeps in my hair and I don’t like people in my hair, you know, so I had to get rid of her.”

Fischer became more and more isolated. Though his chess prowess was getting stronger, at the same time, his mental health was slowly slipping away.

Even by this time, Fischer had spewed a slew of anti-semitic comments to the press. In a 1962 interview with Harper’s Magazine, he declared that there were “too many Jews in chess.”

“They seem to have taken away the class of the game,” he continued. “They don’t seem to dress so nicely, you know. That’s what I don’t like.”

He added that women should not be allowed in chess clubs and when they were, the club devolved into a “madhouse.”

“They’re all weak, all women. They’re stupid compared to men,” Fischer told the interviewer. “They shouldn’t play chess, you know. They’re like beginners. They lose every single game against a man. There isn’t a woman player in the world I can’t give knight-odds to and still beat.”

Fischer was 19 at the time of the interview.

An Almost Unbeatable Player

Wikimedia CommonsBobby Fischer during a press conference in Amsterdam, as he announces his match against Soviet chess master Boris Spassky. Jan. 31, 1972.

From 1957 to 1967, Fischer won eight U.S. Championships and in the process earned the only perfect score in the history of the tournament (11-0) during the 1963-64 year.

But as his success increased, so too did his ego — and his distaste for the Russians and Jews.

Perhaps the former is understandable. Here was a teenager receiving high praise from the masters of his trade. Russian grandmaster, Alexander Kotov, himself praised Fischer’s skill, saying his “faultless endgame technique at the age of 19 is something rare.”

But in 1962, Bobby Fischer wrote an article for Sports illustrated entitled, “The Russians Have Fixed World Chess.” In it, he accused three Soviet grandmasters of agreeing to draw their games against each other before a tournament — an accusation that while controversial then, is now generally believed to be correct.

Fischer was consequently set on revenge. Eight years later, he trounced one of those Soviet grandmasters, Tigran Petrosian, and other Soviet players at the USSR versus the Rest of The World tournament of 1970. Then, within a few weeks, Fischer did it again at the unofficial World Championship of Lightning Chess in Herceg Novi, Yugoslavia.

Meanwhile, he reportedly accosted a Jewish opponent saying that he was reading a very interesting book and when asked what it was he declared “Mein Kampf!”

Over the next year, Bobby Fischer annihilated his foreign competition, including Soviet grandmaster Mark Taimanov, who was confident he would beat Fischer after studying a Russian dossier compiled on Fischer’s chess strategy. But even Taimanov lost to Fischer 6-0. This was the most devastating loss in the competition since 1876.

Fischer’s only significant loss during this time was to 36-year-old World Champion Boris Spassky during the 19th Chess Olympiad in Siegen, Germany. But with his unparalleled winning streak in the past year, Fischer earned a second chance at taking Spassky on.

Bobby Fischer’s Showdown With Boris Spassky

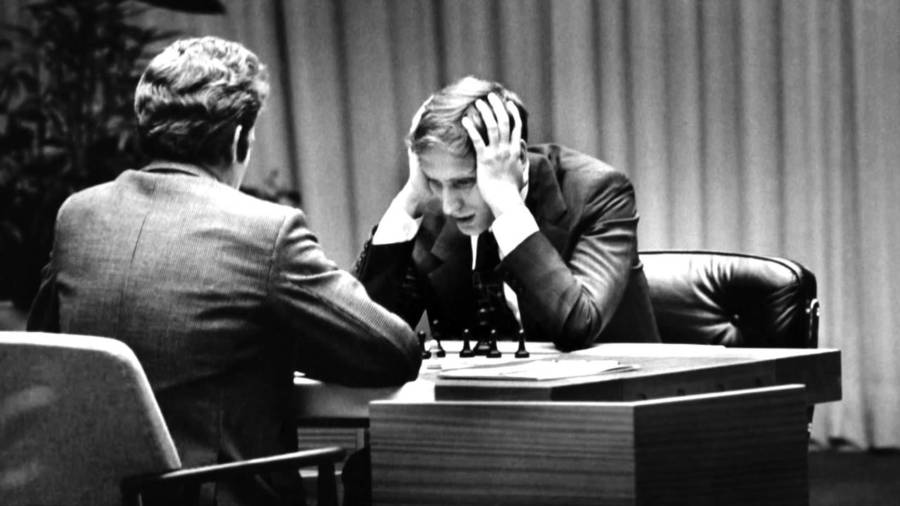

HBODocs/YouTubeBobby Fischer plays against the World Champion, Boris Spassky, in Reykjavík, Iceland. 1972.

When Petrosian had twice failed to defeat Fischer, the Soviet Union feared their reputation in chess might be at risk. They nonetheless remained confident that their world champion, Spassky, could triumph over the American prodigy.

This game of chess between Spassky and Fischer had come to represent the Cold War itself.

The game itself was a war of wits which in many ways represented the kind of combat in the Cold War where mind games had taken the place of military force. The nations’ greatest minds set to fight in the 1972 Chess World Championships in Reykjavik, Iceland where over the chessboard, communism and democracy would fight for supremacy.

As much as Bobby Fischer wanted to humiliate the Soviets, he was more concerned that the tournament organizers met his demands. It wasn’t until the prize pot was raised to $250,000 ($1.4 million today) — which was the biggest prize ever offered to that point — and a call from Henry Kissinger to convince Fischer to take part in the competition. On top of this, Fischer demanded the first rows of chairs at the competition be removed, that he receive a new chessboard, and that the organizer change the venue’s lighting.

The organizers gave him everything he asked for.

The first game commenced on July 11, 1972. But Bobby Fischer was off to a bumpy start. A bad move left his bishop trapped, and Spassky won.

Fischer blamed the cameras. He believed he could hear them and that this broke his concentration. But the organizers refused to remove the cameras and, in protest, Fischer didn’t show up for the second game. Spassky now led Fischer 2-0.

Bobby Fischer stood his ground. He refused to play on unless the cameras were removed. He also wanted the game moved from the tournament hall to a small room at the back normally used for table tennis. Finally, the tournament organizers gave in to Fischer’s demands.

From game three onward, Fischer dominated Spassky and ultimately won six and a half out of his next eight games. It was such an incredible turnaround that the Soviets began to wonder if the CIA was poisoning Spassky. Samples of his orange juice were analyzed, the chairs and lights were checked, and they even measured all kinds of beams and rays that could get into the room.

Spassky did regain some control in game 11, but it was the last game Fischer would lose, drawing the next seven games. Finally, during their 21st match, Spassky conceded to Fischer.

Bobby Fischer won. For the first time in 24 years, someone had managed to beat the Soviet Union in a World Chess Championship.

Fischer’s Descent Into Madness And Eventual Death

Wikimedia CommonsBobby Fischer is swarmed by reporters in Belgrade. 1970.

Fischer’s match had destroyed the Soviet’s image as intellectual superiors. In the United States, Americans crowded around televisions in shopfront windows. The match was even televised in Times Square, with every minute detail followed.

But Bobby Fischer’s glory would be short-lived. As soon as the match was over, he boarded a plane home. He gave no speeches and signed no autographs. He turned down millions of dollars in sponsorship offers and locked himself away from the public eye, living as a recluse.

When he did surface, he spewed hateful and anti-semitic comments over the airwaves. He would rant on radio broadcasts from Hungary and the Philippines about his hatred for both Jews and American values.

For the next 20 years, Bobby Fischer would not play a single competitive game of chess. When he was asked to defend his world title in 1975, he wrote back with a list of 179 demands. When not a single one was met, he refused to play.

Bobby Fischer was stripped of his title. He had lost the world championship without moving a single piece.

In 1992, however, he did momentarily regain some of his former glory after defeating Spassky in an unofficial rematch in Yugoslavia. For this, he was indicted for violating economic sanctions against Yugoslavia. He was forced to live abroad or face arrest upon his return to the United States.

While in exile, Fischer’s mother and sister died, and he was unable to travel home for their funerals.

He commended the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, saying “I want to see the U.S. wiped out.” He was then arrested in 2004 for traveling in Japan with an American passport that had been revoked, and in 2005 he applied for and was reward full Icelandic citizenship. He would live the last years of his life in Iceland in obscurity, inching ever closer to total madness.

Some speculate he had Asperger’s syndrome, others posit that he had a personality disorder. Perhaps he had inherited the madness from his biological father’s genes. Whatever the reason for his irrational descent, Bobby Fischer eventually died of kidney failure in 2008. He was in a foreign country, ostracized from his home despite his prior glory.

He was 64 — the number of squares on a chessboard.

After this look at the rise and fall of Bobby Fischer, read about Judit Polgár, the greatest female chess player of all time. Then, check out the madness behind history’s other greatest minds.