Body snatching at the dawn of the Scientific Revolution was so lucrative that some career graverobbers actually murdered people to satisfy the market.

On April 16, 1788, four boys were playing outside New York Hospital in Manhattan. As the story goes, the children saw a physician-in-training through the window and waved to him. The doctor waved back — but with a cadaver’s severed arm.

According to a version of these events printed in 1873, the mother of one of the boys had just died and the doctor allegedly teased the boy, saying it was his dead mother’s arm with which he had waved.

The group ran home to their parents and the motherless boy told his father about what had happened. Though the father put his boy at ease, the thought of his late wife’s severed arm disturbed him and he consequently went to check on her fresh grave.

But the father was met with the sight of raw soil. His wife’s coffin was open to the air and empty. Instantly recognizing all the signs of body snatching, the father became furious. Within short order, it seemed the whole city had as well.

That’s because New Yorkers had continually read about how medical students at Columbia College had to supply their own research cadavers and did so by grave-robbing the city’s slave, free black, and impoverished graveyards. Robbers were paid by medical students and doctors alike to remove the bodies of loved ones within hours of their burial.

So on that April day in 1788, the city broke out in a riot.

Columbia College Alumnus Alexander Hamilton was forced to try to hold back a mob from the university’s front door. According to some accounts, both former New York Governor and First Supreme Court Justice John Jay and the Revolutionary war hero Baron Von Stueben were present. They were allegedly hit with a rock and a brick, respectively.

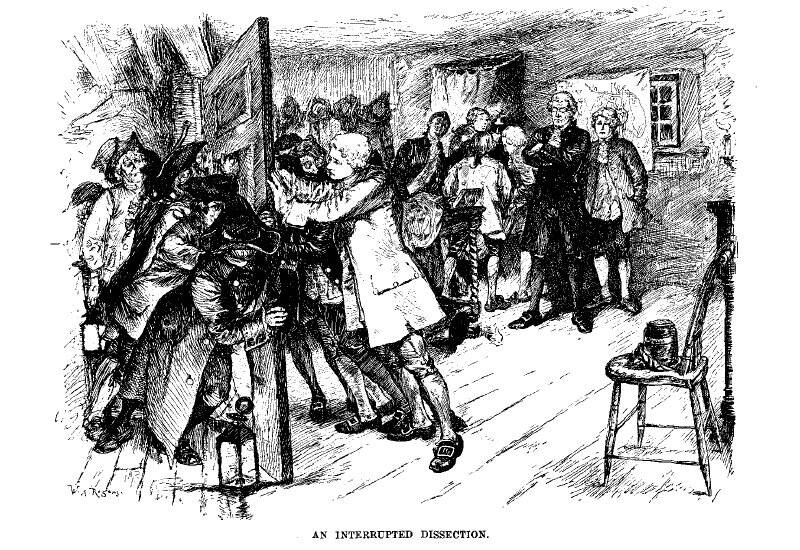

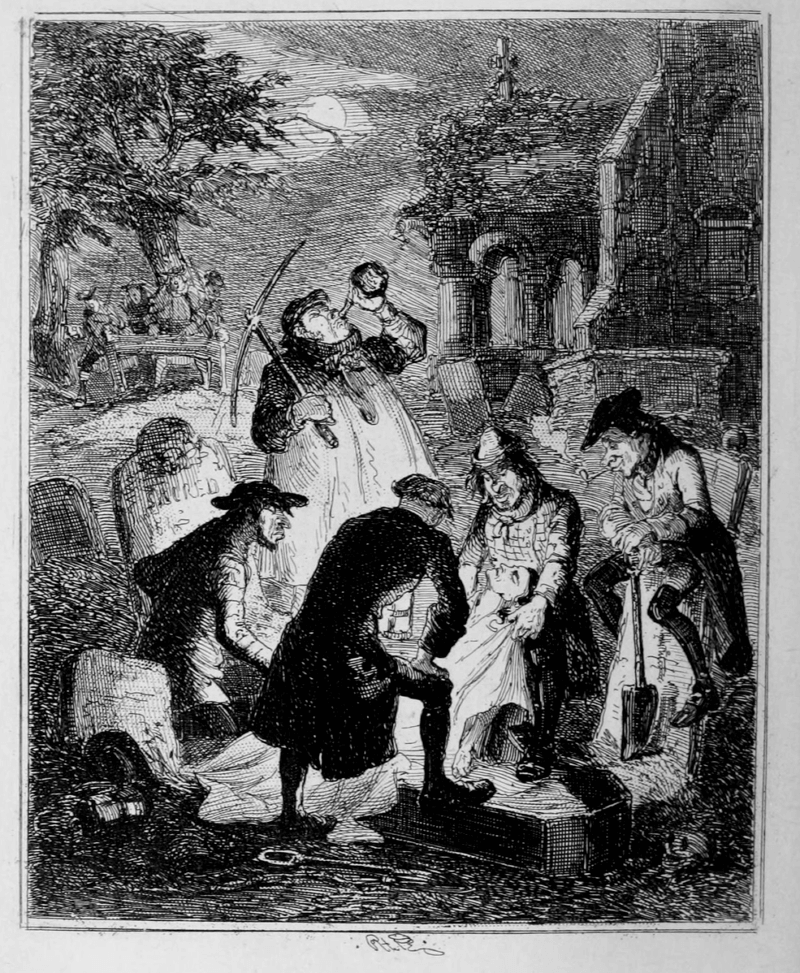

Wikimedia CommonsIllustration of the 1788 Doctor’s Riot titled “An Interrupted Dissection” from a Harper’s magazine story published in 1882.

The mob went from room to room of the university dragging doctors out into the street, beating them mercilessly, and destroying any stolen corpses they found inside. The mob continued to move across the city, chanting “bring out your doctors” until the governor ordered the militia to stop them by force.

It’s believed up to 20 people may have died as a result of this riot.

How Medical Modernization Encouraged Body Snatching

The following year, New York passed the 1789 Anatomy act. It was one of the first American laws that explicitly outlawed grave robbing. However, New York state and New York City were far from the only American locales to witness such macabre struggles.

Between 1765 and 1854, at least 17 doctors’ riots broke out across the country in cities like Baltimore, Cleveland, and Philadelphia.

Prior to the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment, which promoted scholarship, philosophy, and research, medical research had been constrained by widespread Judaeo-Christian religious beliefs.

As per the church’s teachings on the apocalypse and Judgement Day, all dead men would rise to either take their place in heaven or hell. It was believed necessary, then, for dead Christians to remain intact and preserved so that they could rise on Judgement Day to heaven.

Although this belief led to a theological prohibition against cremation as early as the medieval period, it also helped to preserve old models of medicine.

For instance, practices like bloodletting were so alive and well in the 18th-century United States, that they killed President George Washington. At age 67, the first president died of a “throat infection” after having been drained of nearly four liters of his blood — approximately 70-80 percent of the average amount of blood in a healthy adult.

Meanwhile, there were those who knew that the only suitable way to study and systematize medicine would be to experiment on the bodies of the dead.

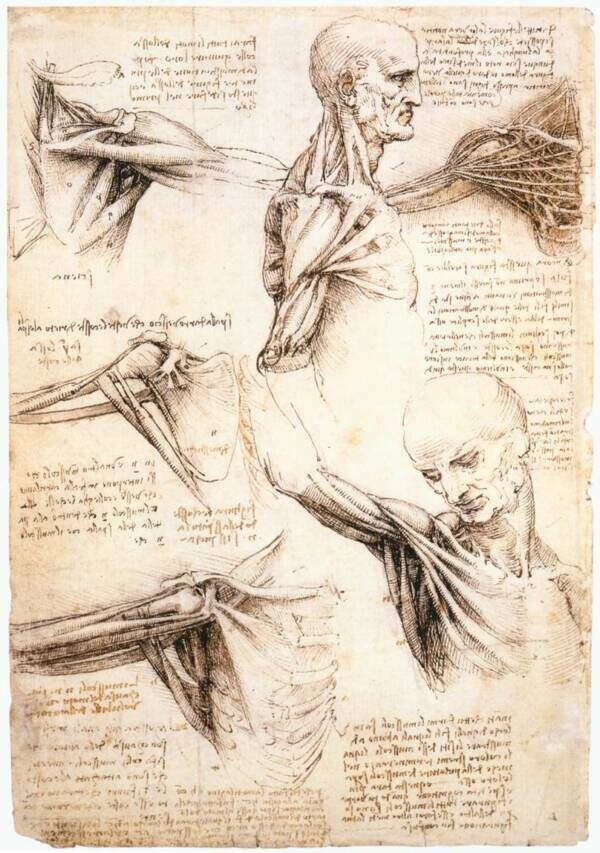

Wikimedia CommonsReference drawings by Leonardo da Vinci based on a partially dissected, illegally acquired corpse. 1510.

As early as the 1400s, scientists and artists like Leonardo da Vinci studied the bodies of the dead to better understand their musculature and subtle structures. But in order to do this, subjects were needed.

In 1536, for example, the 22-year-old doctor Andreas Vesalius began to dig up corpses from Paris cemeteries to study them. He boiled off the body’s flesh to observe the skeleton and wrote notes and corrections into the existing canon on human anatomy.

Due to the macabre nature of these studies and the repressive religious mindset that pervaded this era, it wasn’t so easy for doctors to procure subjects. Often, they were left to their own devices.

A Growing Need For Subjects

When public execution was still popular, it was somewhat easy for researchers to acquire bodies either by stealing them or buying them from an executioner, despite public outcry.

Procuring corpses became even easier for anatomists after parliament passed the Murder Act of 1751, which legalized the medical dissection of convicted murderers as a kind of after-death punishment for them.

Ironically, this Act turned the people against public execution and with the dissolution of executions came the end to a supply of bodies for researchers. Meanwhile, the number of medical schools was growing exponentially in the Age of Enlightenment and scholarship.

Physicians felt that training with dead bodies resulted in both better doctors and better treatment for the living. But, with little access to cadavers now from squeamishness and religious sentiment, physicians had to turn to robbers and thieves to procure subjects.

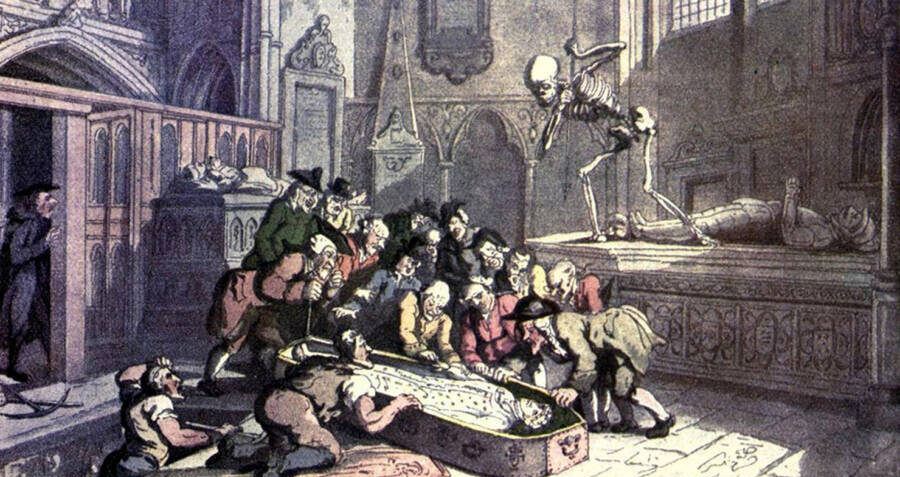

Wikimedia CommonsDeath And The Antiquaries by Thomas Rowlandson. 1816.

As such, archaeological evidence confirms how commonplace dissection became even in areas where it was either outlawed directly or made nearly impossible.

A 2006 dig at the Royal London Hospital at Whitechapel, for instance, unearthed more than 250 skeletons that all showed signs of dissection. Further, the discovery of 1,200 bones from at least 15 people in the basement of a London home once lived in by Benjamin Franklin was attributed to such research as well.

As it always happens in situations like this, where the legal market fails, the illegal one rises to pick up the slack.

The Grave Work In Body Snatching

Becoming a graverobber, body-snatcher, resurrection man, or resurrectionist, in the 18th and 19th centuries required two main qualities.

The first was the strength to dig six or more feet down into a grave, haul up an entire coffin — sometimes just the corpse itself — and refill the hole in a single night.

The second was a stomach strong enough to deal with the occupation and its realities: the smell of decay and the sight of corpses in the middle of the night.

Men like these were apparently fairly easy to find, as for every report of stolen bodies in the 18th and 19th centuries, there would have been a team of no less than three people behind the crimes including a get-away-carriage-driver and a lookout.

What appealed to many criminals about this line of work was that it was easy, arguably victimless, and it offered access to a prestigious, high-paying clientele, namely doctors, who always needed more “goods.”

Indeed, body snatching was a lucrative business. In the United States, a body could fetch between five and $25 in an era where even well-compensated workers might earn just $20 to $25 a week.

In England, there was the added benefit of a legal gray area. Prohibitions against grave robbing as written were focused on the theft of property and valuables like jewelry and coffin adornments and not so much on the actual bodies themselves. As a result, it was not uncommon for British graverobbers to strip down and carry off naked corpses, leaving anything of more traditional value in the grave.

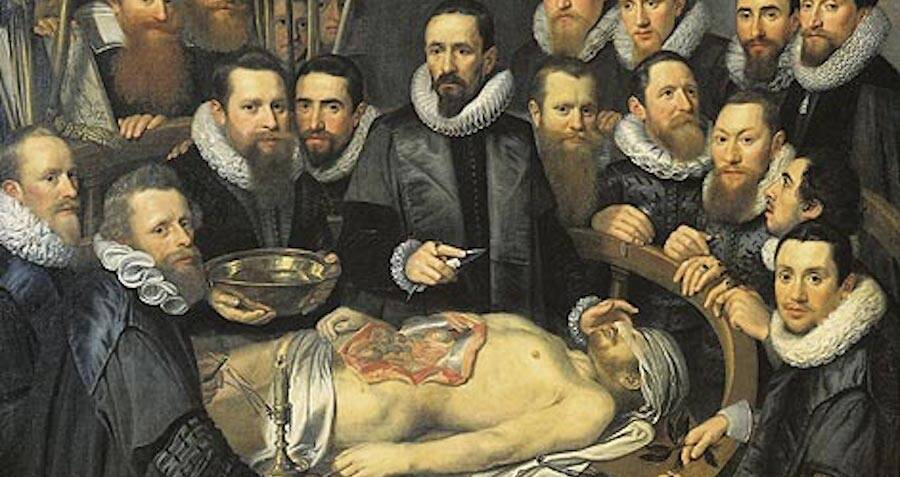

Wikimedia CommonsAnatomy lesson of Dr. Willem van der Meer as drawn by Michiel Jansz van Mierevelt in 1617.

Medical students were seen and in some cases even caught among members of body snatching gangs, leading to persistent speculation (and some evidence) that this is how many aspiring physicians financed their education.

Medical grave robbing required the freshest corpses possible, however, which meant that cadavers quickly became scarce. This led to more thefts, more arrests, and, in some cases, the use of cruel shortcuts to stay ahead of the competition — like murder.

Under the circumstances, it’s hardly surprising that regular civilians started to notice all the missing bodies.

The Bubble Bursts In The Corpse Trade

By the turn of the 19th century, it became commonplace for friends and family to sit by a grave for up to three or four days in the hopes that putrefaction would render the body useless to resurrectionists.

Other families placed a large boulder on top of their loved one’s grave, though that did not prevent resurrection men from digging in diagonally.

Some cemeteries in both the United Kingdom and in the United States introduced graveyard guards to watch over the tombstones at night. Still others opted to solve the problem personally. Mortsafes, above ground iron cages, were erected to protect coffins and many of them can still be seen in some British and American cemeteries today.

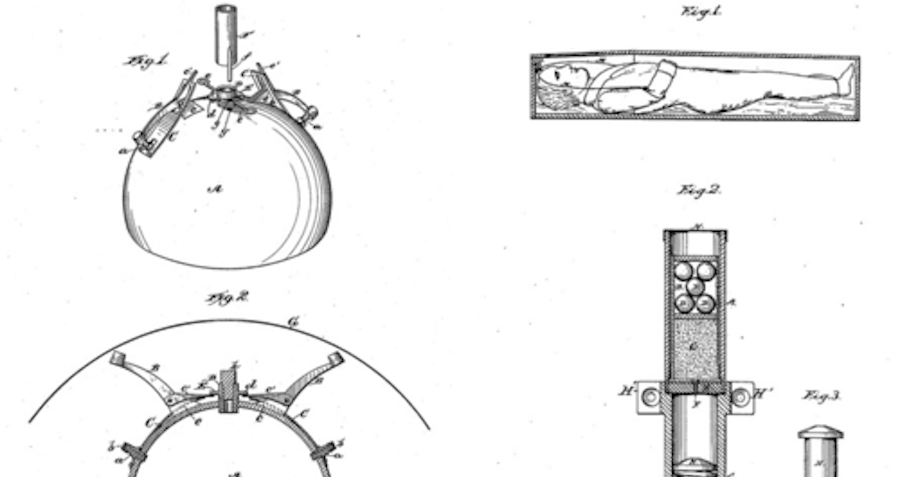

The United States Patent Office recorded dozens of ingenious inventions to protect graves, like guns, alarms, and even a torpedo.

Public DomainThe patent information for the “Grave Torpedo” issued in 1878.

As it became harder to remain competitive in the body-snatching field, some enterprising graverobbers found other unethical ways of improving their overheads.

One such entrepreneur was boxer-turned-expert-graverobber Ben Crouch who called himself “The Corpse King” and claimed to have a virtual monopoly over London hospitals.

A dandy by way of dress, Crouch, wearing gold rings and frilled shirts, would demand exorbitant prices for the bodies he sold and just often steal the bodies back from hospital graveyards after they’d been dissected to sell again to less reputable establishments.

There are other unconfirmed stories concerning his gang delivering obviously murdered bodies or even selling a doctor a drugged man who woke up before the dissection could begin. Nevertheless, Crouch was clever enough to get out of the trade while the getting was good.

In 1817, he and a partner took to following the British army through Europe, collecting teeth from battlefield corpses as they went to sell to dentists.

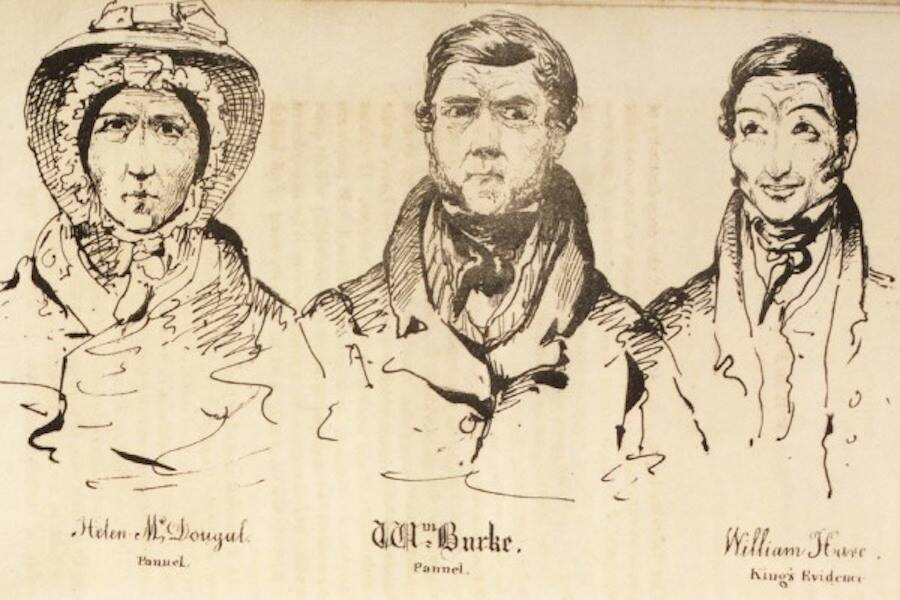

The most infamous of graverobbers cropped up in Edinburgh, Scotland in 1828. Irish-immigrants William Burke and William Hare killed 16 people over the course of 10 months to sell their bodies off to local anatomist and lecturer Robert Knox, who seemed to have known better than to ask questions about the origins of the robbers’ cadavers.

The enterprise began when an indebted lodger died at Hare’s boarding house. Hare sold the body to a local surgeon and not long after that, enlisted Burke’s help in murdering another sickly lodger he felt was scaring off business.

After getting the sick man drunk, Hare held his mouth and nostrils closed while Burke lay across the victim’s chest to impede any noise. Each murder earned the men between the equivalent of 800 and 1,000 pounds in 2019.

Notorious Body Snatchers And Their Comeuppance

Wellcome LibraryBurke and Hare suffocating Mrs. Docherty for sale to Dr. Knox.

Hare and Burke’s unique method, later dubbed “Burking,” was perfect for taking advantage of the fledgling state of forensic science. At the time, it was difficult to tell suffocation from several other types of accidental or natural death and besides, the doctors did not want to know more than they had to.

In one instance, Burke and Hare brought in the body of a beautiful young woman named Mary Paterson and Knox brushed any questions or concerns aside. He happily pickled the lovely corpse in whiskey before dissecting it. Well, Knox would have dissected it had he not been so taken by the naked corpse’s beauty.

Instead, the doctor regularly showed the late Paterson off for admirers. He also hired artists to draw sketches of her. Then, noted surgeon and fellow professor Robert Liston walked into Knox’s office and “found one of the corpses, a young woman named Mary Paterson, in a lascivious pose.”

“Outraged, the powerfully built Liston threw Knox to the floor and retrieved the body for a proper burial.”

Public Domain One of the drawings supposedly based on the body of Mary Paterson.

The macabre antics of Burke and Hare came to an end when they killed local street entertainer, 19-year-old “Daft Jamie” born James Wilson and well-known throughout Edinburgh for his unusually deformed foot.

When Wilson’s body was brought out for dissection in Knox’s class, some students mentioned that it looked like Daft Jamie, who they noticed had been missing. Knox told them they were mistaken before proceeding to dissect the body ahead of schedule and unnecessarily amputating the feet and head.

Wikimedia CommonsSketches from the trial of William Hare, William Burke, and an accomplice. 1829.

Police somehow did not think that Knox’s actions were indicative of someone destroying the evidence of a crime in which he was complicit. He was thus never arrested nor charged and was instead declared “deficient in heart and principle” by forensic investigators.

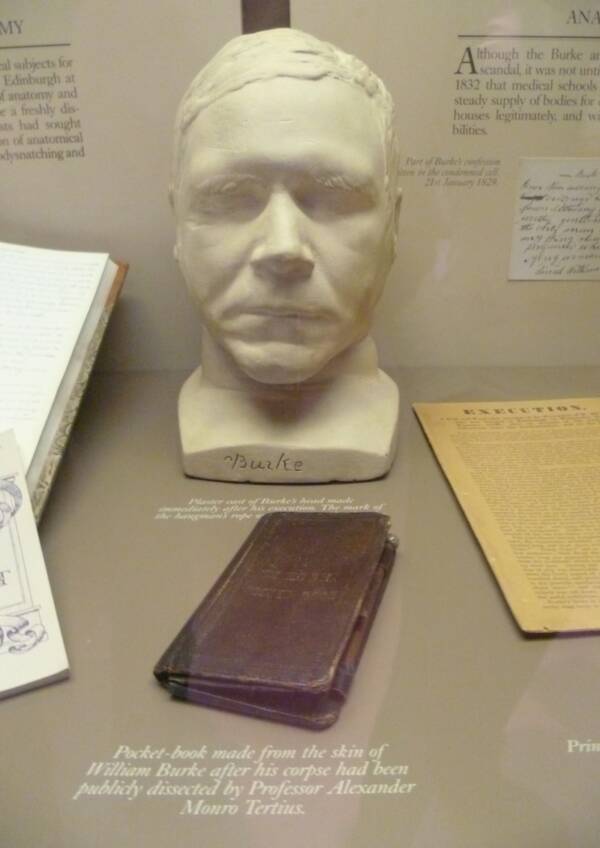

Meanwhile, Hare escaped punishment after testifying against his partner at their trial. On Jan. 28, 1829, William Burke was hanged. His corpse was dissected at the Royal Hall of Surgeons before as many as 30,000 viewers. Burke’s bones have been kept on display in a series of Edinburgh museums for the last 190 years.

As Robert Liston couldn’t have been the first citizen to take notice of the widespread body-snatching epidemic, it seems that something else had to be at play, which kept society mostly quiet on the matter for so long. Indeed, as was the estimation of contemporary observer Sir Walter Scott:

“Our Irish importation have made a great discovery of Economics, namely, that a wretch who is not worth a farthing while alive becomes a valuable article when knocked on the head and carried to an anatomist; and acting on this principle, have cleared the streets of some of those miserable offcasts of society, whom nobody missed, because nobody wished to see them again.”

Wikimedia CommonsThe death mask of William Burke and an appointment book bound in his skin.

In other words, murdering people to sell their cadavers to physicians became a method of targeting and disposing of social undesirables.

Legislating Disenfranchised Bodies For Research

When panic ensued following the crimes and copycat crimes of Burke and Hare, the English parliament took action. They passed the Anatomy Act of 1832, which mandated that all unclaimed bodies — not just those which had been executed — could be dissected. The parliament also introduced a system for body donation.

Architect and philosopher Jeremy Bentham was famously one of the first people to willingly donate his body for dissection. His “auto-icon,” made from his preserved remains, resides to this day at the University College London.

These events opened the path to modern body donation in Britain and greatly reduced the need for the illegal trade, more or less ending the “golden age of grave robbing” across the country.

Wikimedia CommonsJeremy Bentham’s preserved body. Bentham’s head is kept elsewhere but the wax replacement seen here is fitted with his actual hair.

But in the United States, the modernization of dissection was slower in coming.

Not In My Back Graveyard

For one thing, there were no national laws in the United States surrounding grave robbing. Any prosecution for such crimes varied from state to state. The overall impact of these disjointed laws was questionable at best.

In New York, for instance, grave robbing had been illegal for 30 years and the state legislature had grown so frustrated by the number of cases that in 1819, they increased the crime to a felony punishable by a sentence of five years imprisonment.

When that legislation also failed, the state then passed the 1854 “Bone Bill,” which granted doctors and medical schools the rights to all unclaimed corpses and those who died too poor to afford a funeral.

As one supporter for the bill explained, those who had “afflicted the community by their misdeeds, and burdened the State by their punishment; or having been supported by public alms” could “make some returns to those whom they have burdened by their wants or injured by their crimes” by the surrender of their body to science.

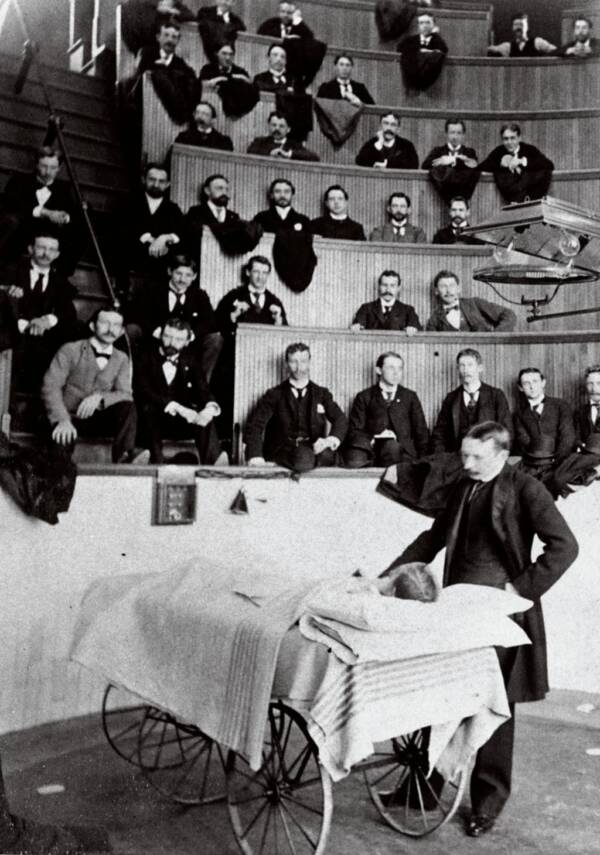

New York UniversityA professor leads an anatomy lecture with a cadaver circa 1885.

The New York “Bone Bill” was passed. It appeared that grave robbing was one thing when it happened to poor, disenfranchised, and decidedly “othered” populations, but when it happened in “polite society” it became an outrage.

For instance, in 1824 the residents of New Haven, Connecticut, noticed that a young woman’s grave had been disturbed in the local cemetery and quickly blamed Yale Medical School.

After getting nowhere with words, a mob assembled outside the building with one of the town’s cannons and had to be kept from firing by the state militia. When finally a group was allowed to search the building, they found and removed the mutilated body hidden in the basement and returned it to its grave.

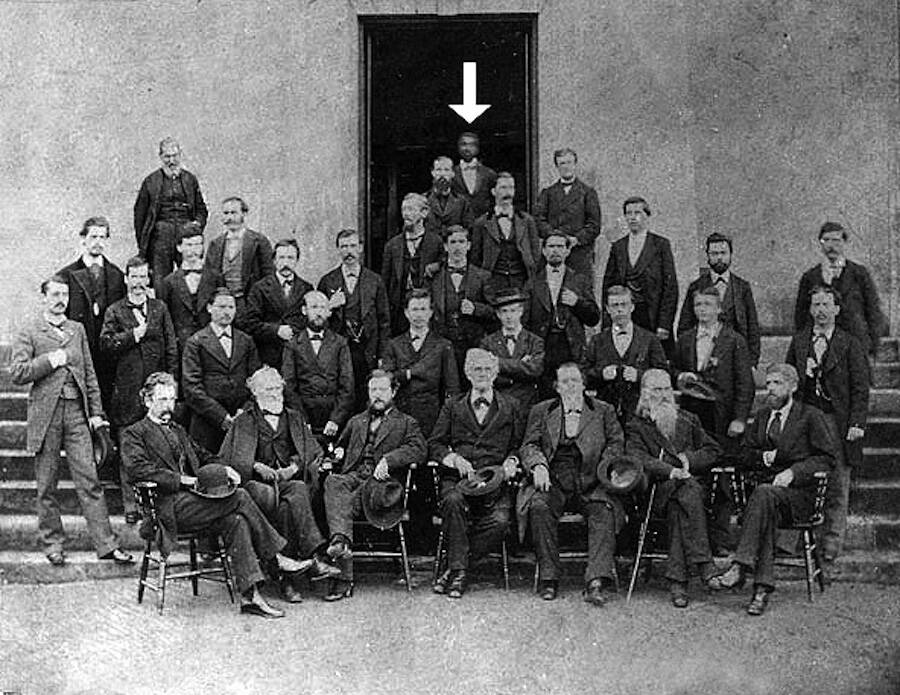

Public DomainGrandison Harris (indicated by the arrow) with the Medical College of Georgia’s Class of 1877.

But by contrast, in Massachusetts, Harvard University moved its medical school to Boston in 1810 where they had better access to cadavers: in a new facility next to an almshouse for the poor.

Similarly, in 1852, the Medical College of Georgia bought a slave named Grandison Harris from the Charleston auctions whose sole job was to retrieve corpses from the Cedar Grove Cemetery’s African American burial grounds outside the city of Augusta.

Harris continued in his role until 1908, when his son replaced him. Later excavations of the Medical College revealed how successful Harris was in his duties: dozens of skeletons, 79 percent of them black, were found in the MCG basement in 1991. After analysis, they were buried in Cedar Grove Cemetery where Harris himself was laid in 1911.

Additionally, during the Dakota War of 1862, there were reports of doctors digging up the bodies of 38 hanged indigenous Dakota warriors for study.

Far be it from witnesses to the largest execution in American history to not find an opportunity therein for anatomical research. One of those doctors, Dr. William Mayo, would go on to use the skeleton of an indigenous American man he called “Cut Nose” in order to teach his sons the rudiments of medicine.

Later, those same two brothers would go on to found the Mayo Clinic and in 2018, the Mayo Clinic apologized to members of the Shantee Dakota tribe for their founders’ indiscretion. The bones of Marpiya Okinajin, known as “Cut Nose,” were returned.

Body snatching continued to ravage the impoverished dead people. In 1882, the superintendent of Pennsylvania’s predominantly black Lebanon Cemetery and a group of resurrectionists were caught digging up a grave.

Afterward, hundreds of black Philadelphians marched on the city morgue demanding the return of six stolen bodies. One newspaper quoted a weeping old woman whose husband’s body had been stolen after she “begged” on the wharves for the $22 necessary to bury him.

After questioning and an investigation, it was determined that the men were, in fact, working on behalf of Dr. William S. Forbes of Philadelphia, a famous and well-respected surgeon, medical lecturer, and Civil War veteran.

Wikimedia CommonsDr. William S. Forbes, painted as if in mid-lecture, by Thomas Eakins.

Forbes protested that the law had increased the number and types of bodies physicians could legally acquire, but the demand for such bodies still vastly overwhelmed the supply.

Forbes claimed that only 400 bodies were provided to his 1881-1882 class of 1400 medical students under the law. Forbes warned: “The debasing trade is stimulated and… practical teachers… find themselves in unworthy competition with each other. Consequently, the price demanded, and often obtained, is such as to tempt the resurrections to enter private cemeteries and graves and even to commit murder, as was the case in Edinburgh in 1829.”

The people of Pennsylvania agreed. In 1883, the state updated its anatomy laws such that all people poor enough to have been buried at the state’s expense would be sent to the medical schools for dissection instead.

Thomas Jefferson UniversityThe teaching clinic of Dr. William S. Forbes at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. Circa 1880s.

Legislation Is Borne Out Of The Theft Of White Bodies

Doctors certainly preferred to snatch bodies that “no one would miss,” but sometimes, they had no choice but to disturb white, wealthy, and well-connected corpses. These were the incidents that brought the most unwanted attention to the macabre practice.

In 1878, John Harrison, grandson of President William Henry Harrison and brother of future President Benjamin Harrison, worried that his father’s grave was in danger when he noted that the adjacent grave had been broken into.

Harrison resolved to visit local medical schools in search of the man’s body. Harrison eventually found the corpse of Ohio Congressman John Scott Harrison, hanging naked from a rope beneath a trap door at the Ohio Medical College.

In response to the outrage, Ohio too passed a new Anatomy Law in 1881, providing doctors and medical schools with access to all unclaimed bodies within the state.

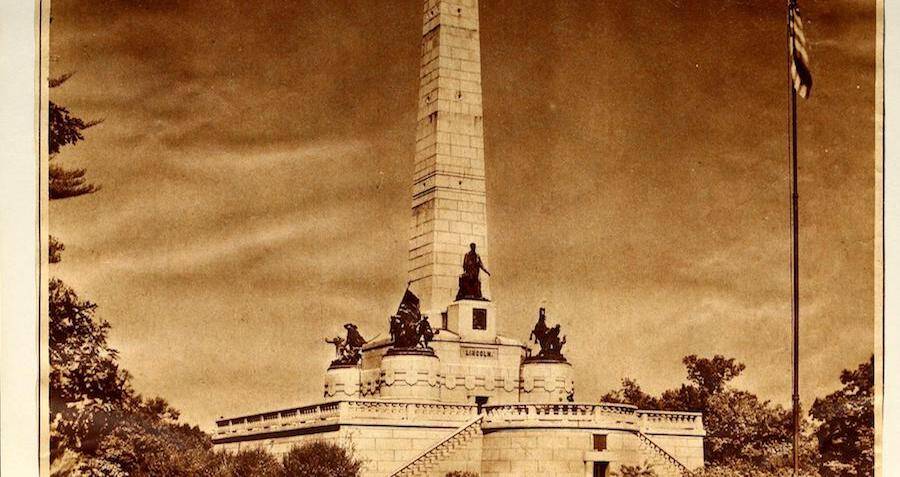

Archive.orgLincoln’s Tomb in Springfield, Illinois first opened in 1874.

While these efforts were usually enough to disincentivize body snatching, they did also promote the rise of a new kind of graverobber.

In 1876, a group of Chicago counterfeiters led by “Big Jim” Kennally attempted to steal the body of Abraham Lincoln from his tomb in Springfield, Illinois.

Unlike most grave-robbing incidents, this was motivated by legal and not medical matters. After stealing the body, the gang planned to use the president’s corpse as a bargaining chip to free one of their members from prison.

We will never know if that plan would have worked because the robbers never got that far.

In search of a “roper,” or someone to pull up the coffin and the body, Kennally and his men accidentally recruited a member of the U.S. Secret Service and were all arrested before the plot even began.

Despite its failure, the plot placed new importance on graveyard security. In 1880, the “Lincoln Honor Guard” was established for the sole purpose of protecting the president’s tomb from body snatching.

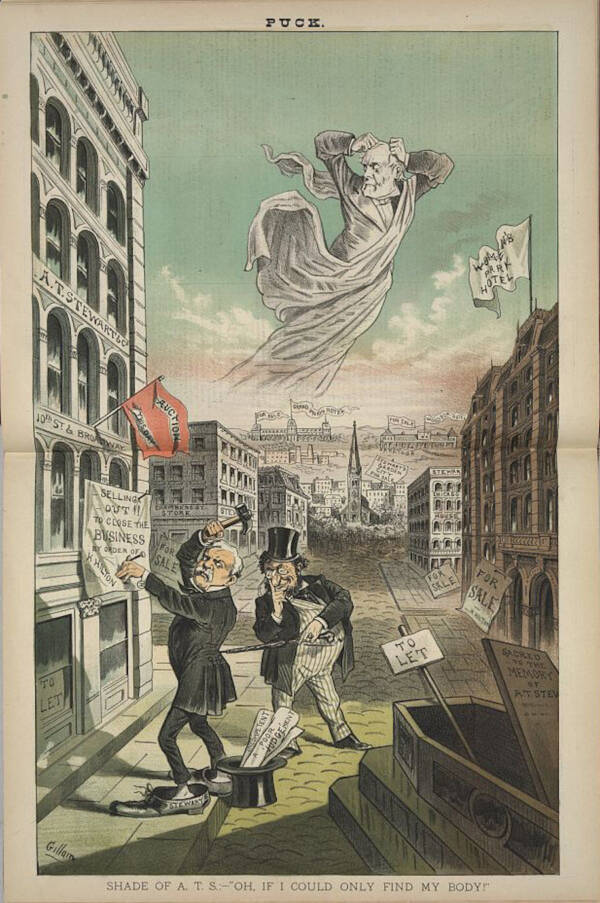

In 1878, the body of Alexander T. Stewart, the wealthy New York merchant and seventh-richest American of all time to this day, was stolen from his grave at St. Marks-In-The-Bowery Church.

The conspirators, or perhaps just people posing as them, sent letters to his widow demanding large payments for the body’s return. But when Mrs. Stewart died in 1886, the mystery had never been officially resolved. In a later memoir, the then-New York Police chief claimed Stewart’s body had been retrieved but there is no evidence to support this other than a marker at the cathedral in Garden City, New York built in his honor.

According to an 1890 legal statement by an assistant of Stewart’s business successor, Mr. Herbert Aynsey however, the body of one of the world’s richest men was never returned.

Library of CongressPuck Magazine cartoon showing the “shade” of Alexander Stewart lamenting the loss of his body and the losses his company went through after his death. 1882.

Apart from medicine, money, and leverage, other reasons to rob a grave included both bragging rights and an opportunity to study the nature of genius.

Body snatching hit its high point at the same time that the pseudoscience of analyzing the shape and size of a skull to determine one’s mental ability came into fashion. The popularity of this pseudoscience, called phrenology, encouraged body snatchers to retrieve the skulls of famous people.

Confirmed and suspected victims of grave robbing for this purpose include the composers Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, the painter Goya, and the Swedish mystic Emmanuel Swedenborg.

Interestingly, it’s possible that Skull and Bones Society at Yale University may be descended from this practice. The exact reasons for the existence of this group and a definitive list of the skulls and skeletons in their possession are not public.

Part of or all of the bones of U.S. President Martin Van Buren, the Apache medicine man Geronimo, the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa, and the mistress of French King Louis XV are rumored to reside within this clubhouse appropriately called “The Tomb.”

Legend has it that Prescott Bush, father of George H.W. and grandfather of George W., stole Geronimo’s skull himself for the group in 1913.

Apart from these outliers, body snatching for medical purposes gradually became a legislated practice across the States. But as more and more states and medical communities came to similar agreements, the shift Forbes had predicted took its toll on the black market.

Body Snatching’s Last Gasp With The “King Of Ghouls”

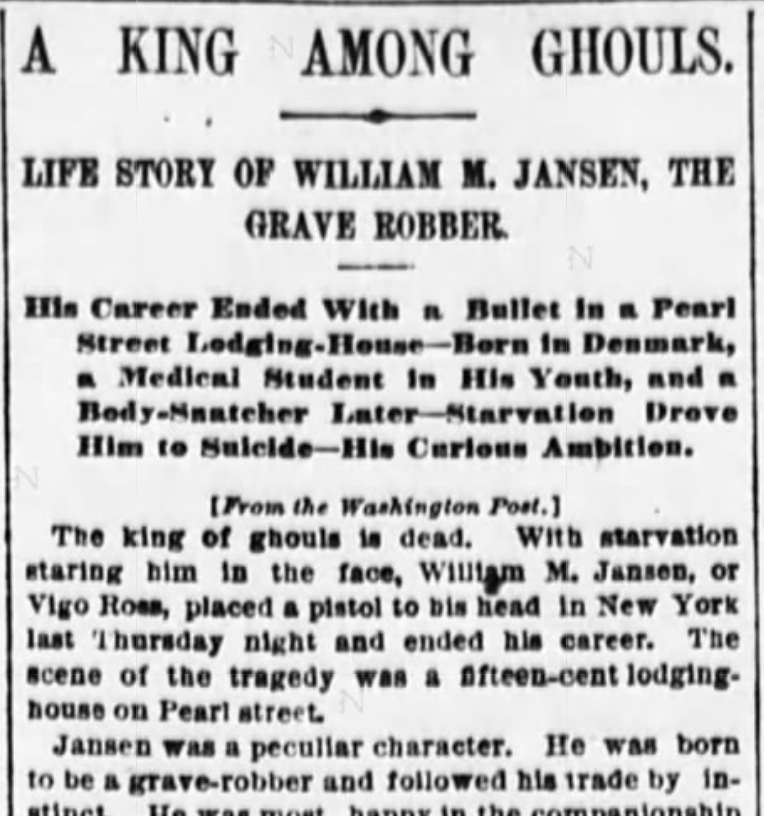

William Jansen, sometimes called Vigo Jansen Ross or the “Resurrectionist King,” was a Danish immigrant who claimed to have had medical training in his native country. His heavy drinking made him an undesirable doctor in the States, however, and at some point, he found himself among the graverobbers.

First arrested for resurrection work in 1880, Jansen’s fame stemmed from his bold theft of the body of Charles Shaw, a criminal executed in Washington D.C. for the murder of his sister.

Within 36 hours of Shaw’s hanging, Jansen had dug up the body, sold it to a medical school, broken into that medical school, stolen it back, and had almost made it to another buyer before he was arrested in January 1883.

Before, during, and after his year-long prison term, Jansen eagerly talked to the press about his exploits, claiming to have stolen and sold more than 200 bodies across the East Coast.

Following his 1884 release, perhaps inspired by the increased legislation over body snatching, Jansen retired as a resurrection man to become a public lecturer. As he told his audiences throughout his tenure, “No one respects a dead person more than I do, but some respect is due to the living.” But if it was respect that Jansen was looking for, he didn’t find it.

Stricken by stage fright, he drank even more heavily when faced with a crowd. However, this probably increased the authenticity of the experience. According to testimony, most graverobbers were drunk most of the time. William Burke had said he kept a bottle of whiskey by his bed to fall asleep and in case he woke up.

Wikimedia Commons

Jansen’s claims to the scientific and medical benefits of his work were met with jeers and insults. At the end of each show, Jansen presented a pantomime of a grave robbery complete with several piles of dirt on stage and an assistant serving as a stand-in for a corpse. The assistant was also incredibly ticklish and did not help the effect by bursting out laughing every time he was picked up.

In 1887, broke, retired from grave robbing, tired of speaking, and “staring starvation in the face,” Jansen shot himself in a rented room at a New York boarding house. The long and surprisingly respectful obituary provided for him by the Washington Post read:

“The king of ghouls is dead…he was born to be a grave-robber and followed his trade by instinct…He was proud, strange to say, of his work and gloried in doing it in a systematic, scientific way. He did not belong to that class of grave-robbers who steal bodies for ransom, but simply sought to supply medical colleges with subjects for dissection.”

Jansen’s passing at the moment laws and their enforcement largely ended traditional body snatching provides as good a place as any to end this historical survey. However, the questions both he and the doctors of his time rose, remain pertinent.

Public DomainObituary for William “Vigo” Jansen, one of the last original graverobbers. This Washington Post article was reprinted in the New York Word on Nov. 9, 1887.

Forgotten, But Not Really Gone

In the mid-1980s, the Indian government placed a blanket ban on the exportation of human body parts after years as the largest source of cadavers, skulls, and skeletons in the world.

Today, India still holds that title, with a large part of the market for these illegal remains being medical schools in Europe and North America.

More recently in 2016, New York outlawed the use of unclaimed bodies in medical schools throughout the state. This system, started with the Bone Bill of 1854, was ultimately brought down by the same sorts of complaints as in the 19th century: mistaken identities and a rushed process that could leave relatives with less than 48 hours to claim a body before it was given over for dissection.

While schools complied (not all willingly), the response given by Dr. John Prescott, the chief academic officer at the Association of American Medical Colleges in Washington D.C., reflects a familiar sentiment that might not have been out of place a century and a half ago:

“Just about every medical school in the United States uses cadavers…We do believe the use of cadavers is critical for training.”

If you enjoyed this article about body snatching, learn about the more recent “resurrection” of John Dillinger and why he was exhumed. Or, if you want to stay in the Victorian vein, maybe you would like this article on the recently-discovered grave of Joseph Merrick a.k.a. “The Elephant Man.”