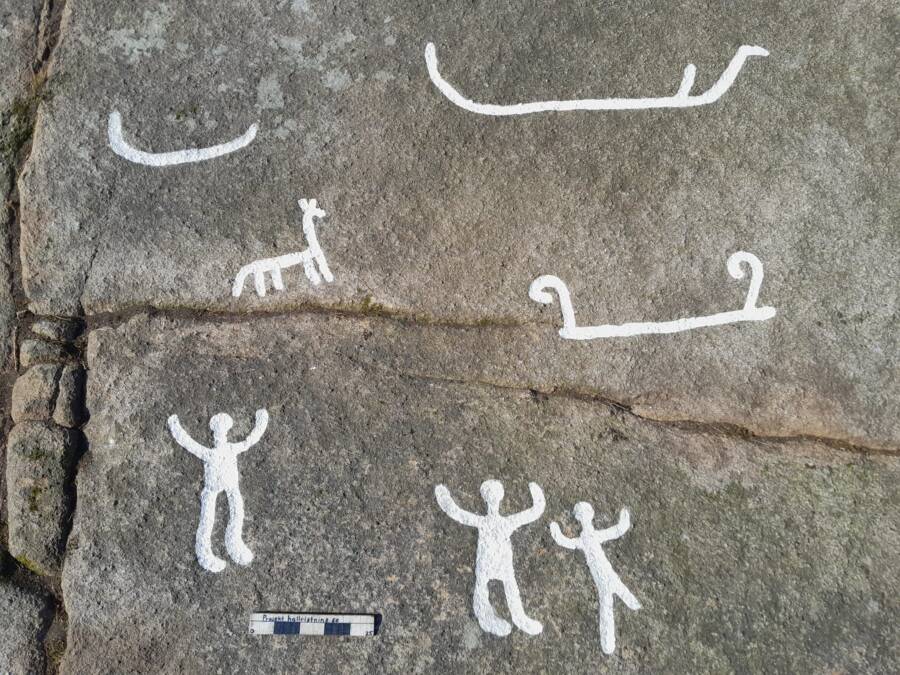

The petroglyphs extend across 50 feet of the rock's surface, with some as long as 13 feet and others only a few inches.

Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock CarvingsThe ancient etchings were created 2,700 years ago in Bohuslän, an area known for its abundance of rock carvings.

Swedish archaeologists recently uncovered a series of around 40 petroglyphs — rock carvings made by chipping at the surface — hidden beneath layers of moss on the side of a cliff face that was once part of an island 2,700 years ago.

“What makes the petroglyph completely unique is that it is located three meters (10 feet) above today’s ground level on a steep rock face that, during the Late Bronze Age, was located on a small island,” the Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock Carvings wrote in a Facebook post. “The petroglyph must have been made from a boat when the sea level was approximately 12 meters (39 feet) above today’s sea level.”

The area in which the petroglyphs were found, Bohuslän, is famous for its abundant rock art. Because of this, it draws in large numbers of tourists each year. It has also been established as a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site.

Researchers were exploring the area near the town of Kville in search of long-undiscovered petroglyphs when they observed a large, moss-covered rock face and noticed distinctive lines that looked like they might be human-made. When they removed the moss, they discovered the numerous petroglyphs beneath it.

“These are very large things, including a two-meter ship and a person over one meter,” archaeologist Andreas Toreld told the Swedish publication Forksning & Framsteg. “The figures are well-carved and deep. The motifs are not unique, but the location on an almost vertical outcrop is unusual.”

Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock CarvingsResearchers believe the four-legged animals depicted in the petroglyphs to be horses.

The petroglyphs depict various figures, including ships, people, and animals. Most of the etchings are between 12 and 16 inches long, and according to researchers, the largest carving shows a ship that is 13 feet long.

Researchers dated the carvings to between the seventh and eighth centuries B.C.E., noting that the verticality of the slab itself makes it easier to date accurately.

“It is twelve meters above today’s sea level. Then it cannot be older than the eighth century B.C.E.,” Toreld said. “But the unusual thing is that we also have a limit ahead. If it was younger than the seventh century, the carvers would have needed a ladder or platform, and it seems unreasonable that they would have carved in a straight line three meters from the ground.”

Petroglyphs on flatter slabs are generally more difficult to date, as they have fewer environmental indicators of the time of their creation.

Speaking to Live Science, Martin Östholm, an archaeologist and project manager with the Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock Carvings, explained that to create these etchings, the artists would have had to stand on a boat or a platform made of ice, repeatedly striking the rock face with hard stones to create the images.

Large granite stones such as this exposed a layer of stark white beneath the outer, deep gray, making the etchings highly visible even from a distance. Östholm said it is not clear why Bronze Age Swedes created the carvings originally, but theorized that they may have been used to mark ownership.

Foundation for Documentation of Bohuslän’s Rock CarvingsOne exceptionally tall, roughly three-foot etching of a man.

However, James Dodd, a researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark who was not involved in the discovery, offered another theory.

“On the basis of the repetition of the motifs, it is possible that this collection of figures forms a narrative,” Dodd said. Studies of other petroglyphs in the region have led researchers to similar conclusions in the past as well. Other theories have previously identified petroglyphs as having ties to ancient cult and religious practices.

But while the true meaning of the carvings may remain a mystery, there is no doubt as to the historical and archaeological significance of this discovery.

After reading about these newly discovered rock carvings in Sweden, explore the mystery of Peru’s Nazca lines, petroglyphs on a massive scale. Or, learn about five lost civilizations throughout history.