Once a bustling hub for the steamboat and railroad industries, the town of Cairo, Illinois now sits abandoned due to economic decline and racial violence.

Named for the city in Egypt, Cairo, Illinois (pronounced CARE-o), began as a small town with big dreams. Perched at the junction of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, it seemed strategically placed to become a major hub — and some even suggested that it should become the new capital of the United States. But Cairo’s rosy future never materialized.

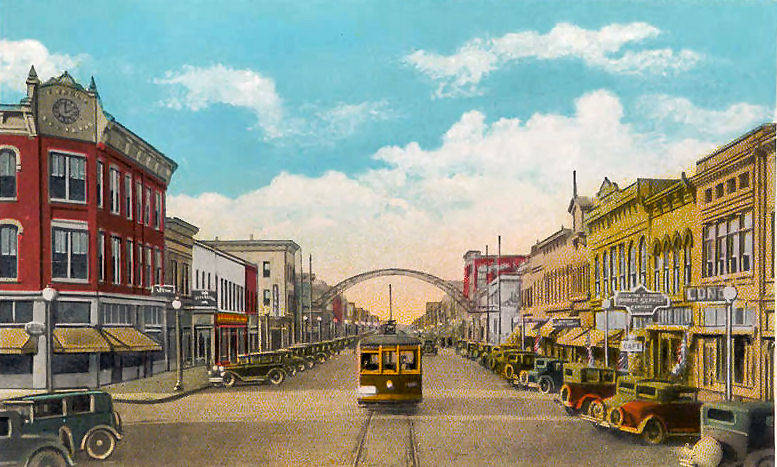

Today, the city is essentially a ghost town. Shuttered buildings line its streets, and the population has dropped steadily since the early 20th century. In the 1920s, there were more than 15,000 residents in Cairo — but that number has since plummeted to less than 2,000.

So, what happened?

The reasons for Cairo's decline are myriad. It has a difficult climate, is prone to flooding, and has been overshadowed by larger cities. Cairo also suffered from a spate of bad luck, like when a railroad bridge was built in nearby Thebes, robbing Cairo of its dreams of becoming a key railway hub.

But perhaps the greatest factor in Cairo's decline was its racial strife. After new Black residents poured into the city during and after the Civil War, Cairo became the site of horrifying racial violence. Its unwillingness to change over the next century, especially when it came to desegregating public spaces and establishing fair hiring practices, also rang the city's death knell.

This is the story of Cairo, Illinois, from its promising beginnings to its current status as an American ghost town.

The Establishment Of Cairo, Illinois

Before it became Cairo, Illinois, the area was a fort and tannery for some of the first French traders who arrived in 1702. However, their operation was cut short after Cherokee warriors slaughtered most of them. A century later, the area at the confluence of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers played a role in the Lewis and Clark expedition, as the explorers camped there while learning how to determine latitude and longitude.

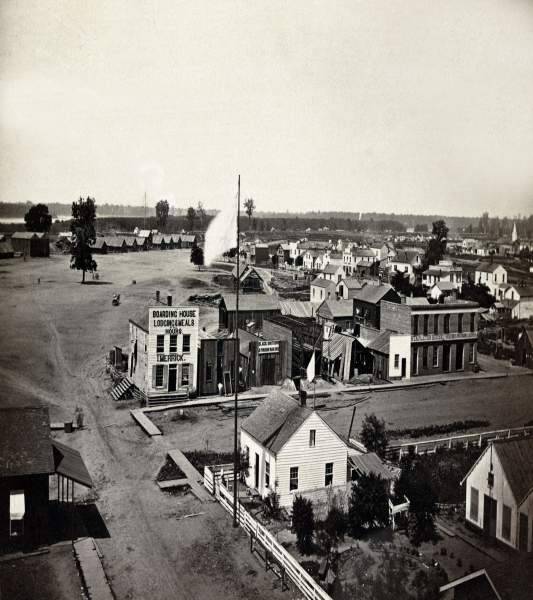

Public DomainCairo's main street, Commercial Avenue, during the height of the port town's economic prosperity. 1929.

According to James M. Lansden's A History of the City of Cairo, Illinois, John G. Comegys of Baltimore bought 1,800 acres in southern Illinois in 1817 and named the land "Cairo" in honor of the historic city of the same name on the Nile Delta in Egypt. Comegys hoped to turn Cairo into one of America's great cities, but he died before his plans could be realized. The name, however, stuck.

It wouldn't be until 1837, when Darius B. Holbrook entered the town, that Cairo really took off. Holbrook, more than anyone else, was responsible for the city's establishment and early growth.

As president of the Cairo City and Canal Company, Holbrook set a few hundred men to work constructing a small settlement that included a shipyard, a farm, a hotel, and several residences. However, Cairo's susceptibility to flooding was a major obstacle in establishing a permanent settlement. Holbrook's plan initially faltered as the new town's population fell by more than 80 percent.

Indeed, not everyone shared Holbrook's optimism. When Charles Dickens visited Cairo in 1842, he described it as a "detestable morass" and a "breeding-place of fever, ague, and death." He purportedly based the hellish city of Eden in his novel Martin Chuzzlewit on Cairo.

Holbrook, however, remained confident. Despite earlier disappointments, he next sought to add Cairo as a station stop along the Illinois Central Railroad. By 1856, Cairo was connected by rail to Galena in northwest Illinois.

This set Cairo on the path to becoming a boom town within just three years. Cotton, wool, molasses, and sugar were being shipped through the port in 1859, and the following year, Cairo became the seat of Alexander County.

Cairo's Role In The Civil War

By the outbreak of the Civil War, Cairo's population was 2,200 — but that number was about to explode.

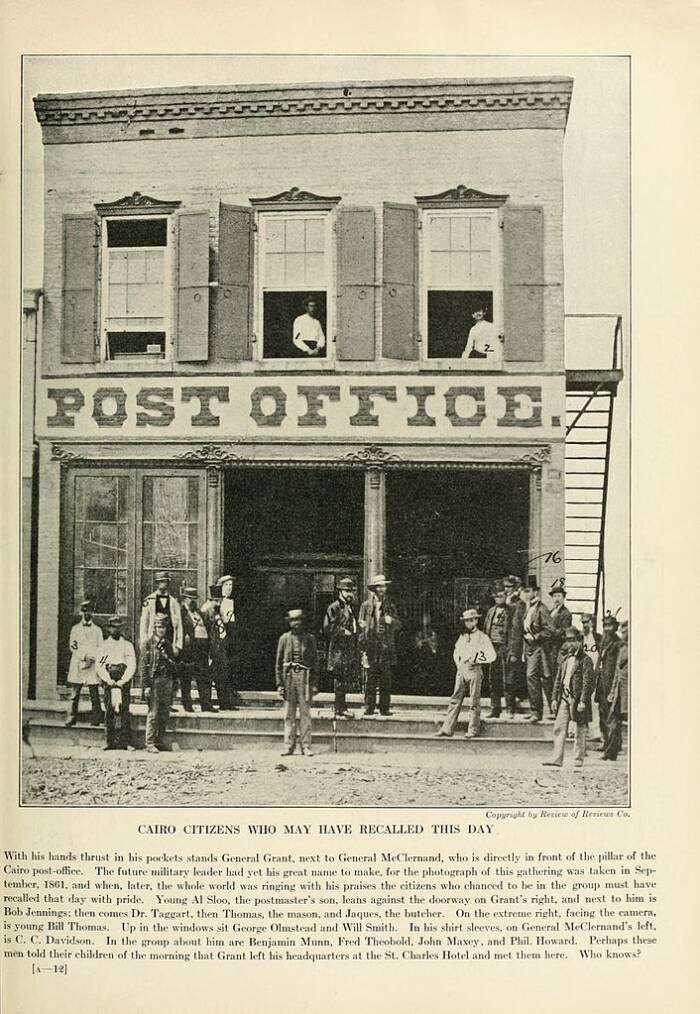

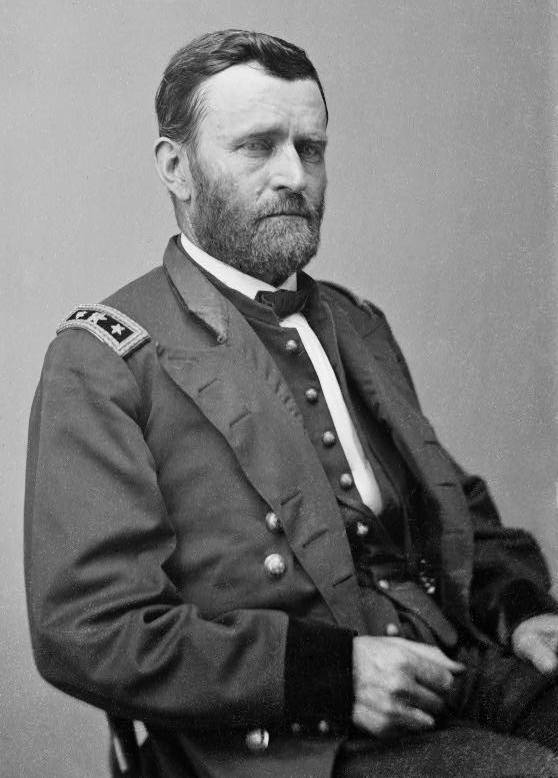

The city's location along both a railroad line and a port was strategically important, and the Union capitalized on this. In 1861, General Ulysses S. Grant established Fort Defiance at the tip of Cairo's peninsula, which operated as an integral naval base and supply depot for his Western Army.

Library of CongressGeneral Ulysses S. Grant used Cairo as a strategic advantage against the Confederate South because of its location.

The number of Union troops stationed at Fort Defiance swelled to 12,000. Unfortunately, this occupation by Union troops meant that much of the town's trade by rail was diverted to Chicago.

Meanwhile, it is suspected that Cairo operated as a key city in the Underground Railroad. Many enslaved people who escaped the South and made it into the free state of Illinois were then transported to Chicago. However, by the end of the war, more than 3,000 former slaves had settled in Cairo, according to the Washington Times.

With a growing population and commerce, Cairo was poised to become a major city. Some even suggested that it should become the new capital of the United States. However, the troops did not like the humid climate, which was made worse by the muddy, low-lying land that was so susceptible to flooding.

Future Secretary of the Treasury George S. Boutwell wrote in his 1902 memoir, "Our life at Cairo was disagreeable to an extent that cannot be realized easily."

As a result, when the war ended, the soldiers packed up and went home.

Racial Tensions And Lynchings

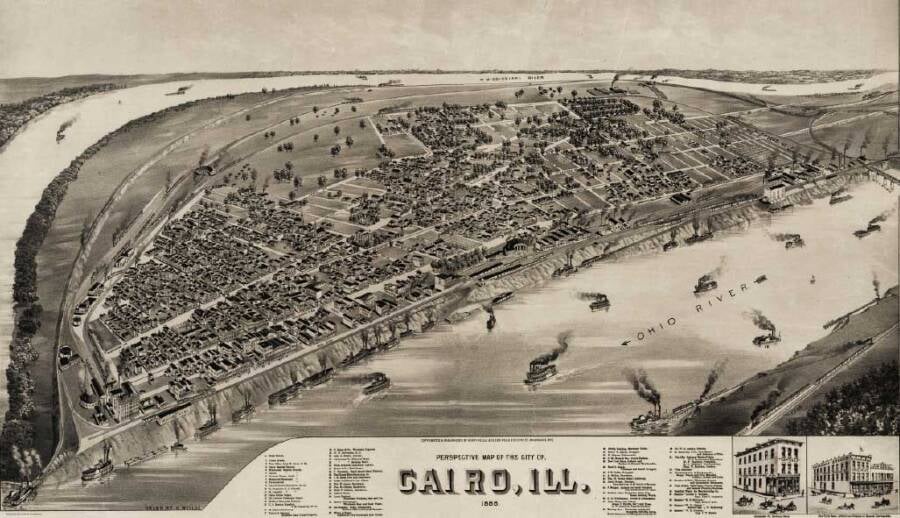

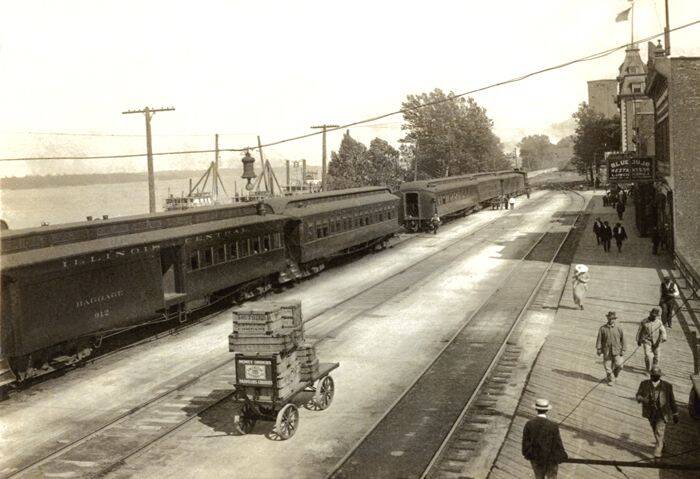

Despite the post-war population exodus, Cairo's location and natural resources continued to attract breweries, mills, plants, and manufacturing businesses. Cairo also became an important shipping and steamboat hub. By 1890, the town was connected to the rest of the country by water and several railroads, and it acted as an important way station between larger cities.

But during those prosperous years of the late 19th century, segregation took root, and Black residents (who made up about 40 percent of the population) were forced to build their own churches, schools, and businesses.

They also formed the bulk of the unskilled labor force. These men were highly active in unions, strikes, and protests that campaigned for equal rights in education and employment. Such protests also demanded equal representation in local government and the legal system as the Black population continued to grow.

Cairo was dealt a hard blow in 1905 when a new railway bridge opened up the neighboring town of Thebes as a port of trade. The competition was devastating to Cairo, and white business owners faced a severe downturn and began taking out their frustration on Black business owners, setting the stage for racial tension and violence.

That violence escalated on Nov. 11, 1909, when a Black man named William "Froggie" James was accused of raping and murdering Anna Pelley, a 24-year-old white woman, despite the fact that there was no real evidence connecting him to the crime. Expecting violence, Cairo's sheriff hid James in the woods. This was to no avail.

A mob formed and dragged James to the town's center at 8th Street and Commercial Avenue. Several men tied a noose around James' neck and hanged him from the steel arches that spanned the intersection — but the rope snapped.

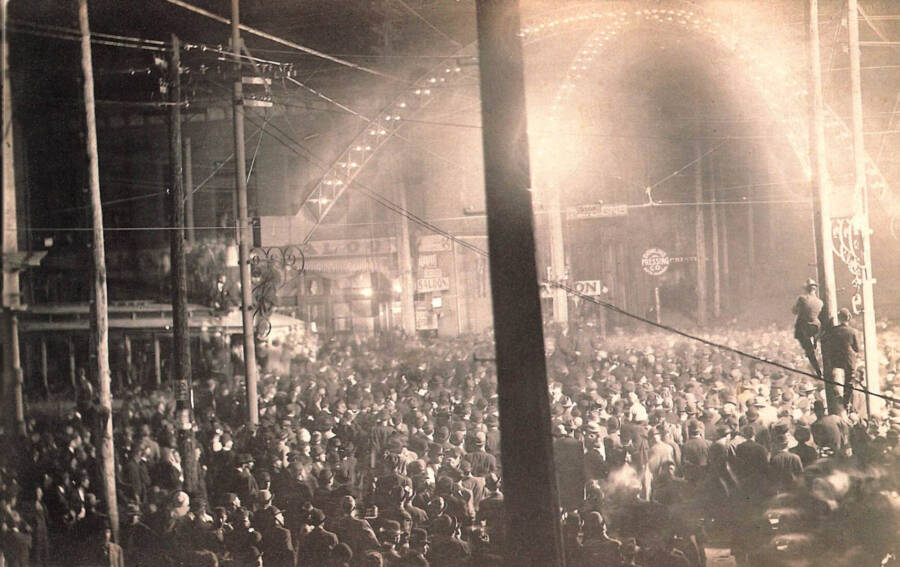

Public DomainThe lynching of William "Froggie" James on Nov. 11, 1909.

When James plummeted to the ground, still apparently alive, the angry mob riddled his body with more than 500 bullets. They then dragged him to the site of Pelley's death and burned him before a crowd of some 10,000 people. (Cairo's population at the time was around 14,000.)

James' head was stuck on a pole, and the bloodthirsty crowd cut off other parts of his body as macabre souvenirs. But they weren't done yet.

The mob then marched to the county jail and abducted Henry Salzner, who had been charged with murdering his wife. Salzner was ripped from his cell, dragged to the town center, lynched, and shot.

All the while, Cairo's mayor and chief of police remained barricaded in their homes. Illinois Governor Charles Deneen was forced to call in the National Guard to quash the chaos.

Unfortunately, this incident was only the beginning of racial violence in Cairo, Illinois. The following year, a sheriff's deputy was killed by a mob attempting to lynch a Black man for stealing a white woman's purse.

By 1917, Cairo had developed a violent reputation as the town with the state's highest crime rate, one that stuck even decades later. By the late 1930s, Cairo had the highest murder rate in Illinois. Mired in the depths of the Great Depression, businesses shuttered, and many residents left. In the 1950s, the town also became a hotspot for illegal gambling and bootlegging.

However, it was racism that ultimately led to Cairo's demise.

Cairo's Residents Resist The Civil Rights Movement

During the 20th century, Cairo's Black residents pushed for equal treatment. In 1946, Black teachers in Cairo filed a lawsuit to demand equal pay. They were defended by none other than future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, then the chief counsel of the NAACP.

Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts Amherst LibrariesA civil rights demonstration in Cairo, Illinois. 1962.

Hattie Kendrick, one of the plaintiffs, later recalled the demeaning way the defense attorney treated Marshall.

"Thurgood and this other attorney were being called 'boys' by the defense attorney," she said, according to the Cairo Association Of Teachers.

"He went on about how only a 'brilliant attorney' like the one who'd won a case like this in Tennessee could win this one. After he finished, Thurgood got up and bowed to him and thanked him, saying: 'I am that qualified, brilliant attorney who handled that case.' The whole courtroom burst into laughter."

In 1952, further efforts were made to integrate Cairo's schools. But though the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education ruled that segregation in public schools was unconstitutional in 1954, Cairo didn't integrate its schools until 1967.

Indeed, the town remained stubbornly segregated. Instead of hiring Black residents in the 1960s, businesses in Cairo brought in white employees from neighboring states like Kentucky and Missouri. When Black citizens protested against the city's segregated public swimming pool, it became a private "club" to keep them out. And when that didn't work, the city shut it down and filled it in with concrete.

Cairo's racist policies even attracted the attention of the state government. When banks in the city refused to hire Black employees, the state threatened to withdraw its financial support.

formulanone/Wikimedia CommonsBoarded up buildings in Cairo in 2020.

But it was the suspicious death of 19-year-old Black soldier Robert Hunt while on leave in Cairo in 1967 that finally did the town in. Black residents did not believe that Hunt had died by suicide in his jail cell after being arrested on disorderly conduct charges, as the coroner had reported. Protestors faced violent opposition from white vigilante groups, and soon, the Illinois National Guard was once again called in to stop the violence after days of fire bombings and shootouts in the streets.

In 1969, according to a 1987 report in the Washington Post, Cairo suffered through 170 days of reported sniper fire. Between 1968 and 1972, the town had such a reputation that its high school teams played every game as an away game because no other high schools would willingly come to Cairo.

During that period, a new vigilante group called the White Hats formed. Members threatened any Black residents who dared gather at sports games, parks, or marches. In response, citizens formed the United Front of Cairo to end segregation. The United Front boycotted white-owned companies, but the white residents refused to give in, and one by one, businesses began to close.

carlfbagge/FlickrAn abandoned business in downtown Cairo, Illinois.

In April 1969, Cairo's streets resembled a war zone. The White Hats were disbanded by the Illinois General Assembly, but still, white residents resisted. The town entered the 1970s with less than half of the population it had in the 1920s. With continued shootings and bombings fueled by racial unrest, most businesses closed, and those determined to hold on were boycotted.

Cairo, Illinois, limped into the 1980s and remarkably still holds on to this day — in name, at least. The downtown sits abandoned, and the signs of its once great economic promise are long gone. The city's violent and racist history has snuffed out any hope for progress. Some new businesses open periodically, but they soon close, and tourism is not actively promoted. The population, which peaked at more than 15,000 residents in the 1920s, sits around 1,700, nearly 10 percent of what it was a century ago.

In the gallery above, discover Cairo's rise and fall, from its hopeful beginnings to its fate as a ghost town. Today, the abandoned, once-prosperous streets of Cairo, Illinois, serve as a sad monument to the destructive forces of racism.

After this look at Cairo, Illinois, view these photos of the toxic ghost town of Picher, Oklahoma. Then, learn why Centralia, Pennsylvania, was abandoned.