Known as "The Godfather" of the New Orleans Mafia, Carlos Marcello was a prime target of President Kennedy's campaign against organized crime.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesCarlos Marcello (center) was known as Louisiana’s “most sinister racketeer boss” and single-handedly ran the New Orleans crime family from the 1940s through the 1980s.

In the history of New Orleans, few mobsters are as mythologized as Carlos Marcello. Beginning in 1947, he ruled the New Orleans Mafia as “The Little Man” out of a small office at the Town and Country Motel in nearby Metairie along Airline Highway, where he became a powerful political dealmaker, multi-millionaire real estate developer, and cultural icon of Louisiana.

To some, he was a kindly neighborhood presence, tomato salesman, and shrimp boat owner. But to the Senate Rackets Committee, headed by Robert F. Kennedy, he was “one of the worst criminals in the country.” And after November 22, 1963, his legend became forever tied to his alleged involvement in the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

Marcello spent the remainder of his life fighting deportation from the U.S. Because he’d been born abroad and immigrated when he was eight months old and never bothered to apply for citizenship, the U.S. government spent decades trying to get rid of him.

But while they briefly succeeded, Carlos Marcello returned undaunted — and continued his reign as the godfather of New Orleans’ Mafia for decades until he died at the ripe old age of 83.

The Early Petty Crimes Of A Future Mafia Boss

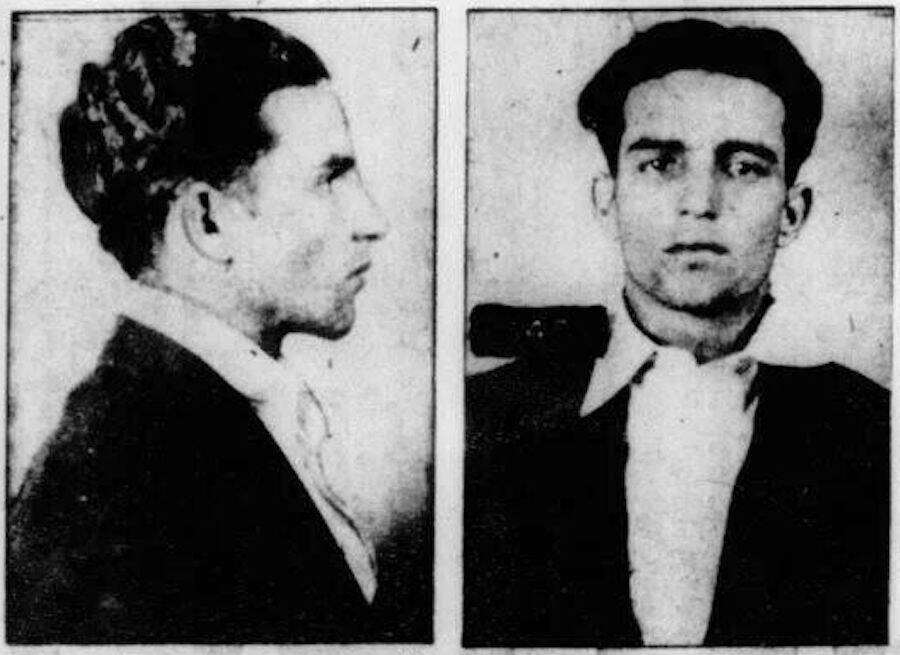

Public DomainCarlos Marcello’s 1929 mugshot by the Louisiana Bureau of Identification after he was first arrested for petty theft in the French Quarter.

Carlos Marcello was born on Feb. 6, 1910, in a colonial outpost of Sicily in Tunis, Tunisia. He arrived in New Orleans with his family the following year. His Sicilian parents took on anglicized names, renaming young “Calogero Minacore” Carlos Marcello. Marcello remained the only undocumented one of his eight younger siblings — a status that would have far-reaching future repercussions later in his life.

By Marcello’s arrival, New Orleans had a Sicilian population of over 200,000. The city was fertile ground for organized crime, and the Sicilian Black Hand gang was fast becoming America’s first Cosa Nostra family. Under street boss Silvestro “Silver Dollar Sam” Carollo, America’s founding Mafia family controlled various rackets along the docks.

As a teenager, Carlos Marcello lived in the Lower French Quarter, colloquially known as Little Palermo. According to Bayou Brief, Marcello became involved in petty crimes, getting to know the gangsters of the neighborhood.

By 19, he ran a youth gang and had two teenage boys rob a grocery store. The boys, arrested and bowing to police pressure, named Marcello as their sponsor, relegating him to a nine-to-14-year sentence in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola.

How Carlos Marcello Became The New Orleans Family Boss

Bettmann/Getty ImagesCarlos Marcello (center) in New Orleans, June 7, 1961.

Carlos Marcello’s big underworld break would come from the Prime Minister of organized crime: Frank Costello, the nominal boss-of-the-bosses in New York.

By 1935, Costello had decided to uproot his gambling slot machine empire. New York had become unreceptive to his endeavors as Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia created a media spectacle of smashing slots with a sledgehammer and throwing them into Long Island Sound.

Seeing an opportunity for his state, Louisiana Senator and former governor Huey Long stepped in. With a shadow investment from Meyer Lansky and his political connections in Louisiana, all Costello needed now was a trustworthy local to run his New Orleans end. And he wanted Carlos Marcello.

Marcello’s imprisonment at Angola would prove to be no deterrent. Costello, a master of political manipulation, had a local legislator visit the state’s governor, O.K. Allen, who released Marcello and fully pardoned him after just five years in prison, according to Bayou Brief.

Marcello created the Jefferson Music Company, a jukebox and pinball distribution company in his brother’s name. Hundreds of Costello’s slot machines were rolled out into the bars of the French Quarter and across Jefferson Parish. And Marcello established his political connections and influence by paying off politicians and police officers across the state.

Over the next decade, Marcello acquired an impressive portfolio of land and businesses, including a shrimp boat fleet. And in 1947, with former boss Silvestro Carollo deported to Italy, Marcello received approval from the Mafia commission to become New Orleans’ new boss at age 37.

Carlos Marcello’s Deportation By Robert F. Kennedy

Bettmann/Getty ImagesAs U.S. attorney general, Robert F. Kennedy cracked down hard on Mafia activities.

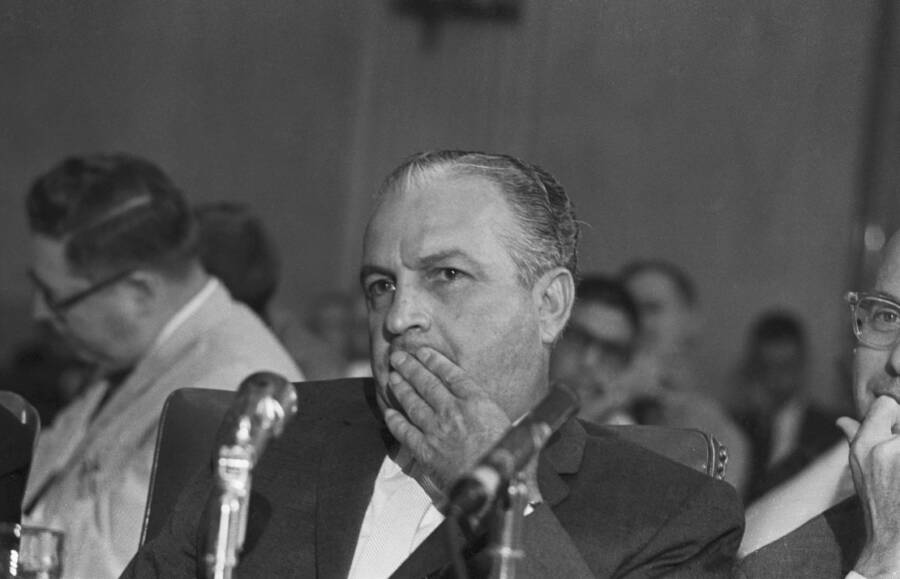

Twice in the 1950s, Carlos Marcello was summoned to testify before U.S. Senate committees investigating racketeering and the Mafia. And both times, he invoked his Fifth Amendment rights, refusing to answer questions that might incriminate him. It was an embarrassment to the committees. But one senator took it particularly personally: Robert F. Kennedy.

After John F. Kennedy became president in 1961, he appointed his brother Robert as U.S. attorney general. Robert F. Kennedy immediately began his legal assault on Mafia bosses and made Carlos Marcello one of his top priorities.

Kennedy’s ace in the hole was Marcello’s immigration status. Marcello had never applied for U.S. citizenship. For eight years, Marcello had been required to present himself to immigration authorities every three months.

On April 4, 1961, Carlos Marcello and his lawyer attended their quarterly appointment. But under Kennedy’s orders, Marcello was handcuffed and deported to Guatemala, where he claimed to hold citizenship under a forged birth certificate.

The Guatemalan government deported him to neighboring EL Salvador, where he was forced to cross the Honduran border on foot the following day. But Marcello allegedly reentered the U.S. only months later on one of his shrimp trawlers through the Louisiana bayou.

Marcello was then hit with a litany of charges. Illegal entry into the U.S., perjury, and evasion of hundreds of thousands of dollars in federal taxes. According to Selwyn Raab’s book Five Families, Marcello seethed and blamed Robert F. Kennedy and his president brother exclusively.

Was Carlos Marcello Involved In JFK’s Assassination?

There existed plenty of circumstantial evidence linking Carlos Marcello to the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. The 1979 House Select Committee on Assassinations (HSCA) report listed a 1962 conversation between Marcello and business associate Edward Becker during which Marcello said, “Don’t worry about that little Bobby son-of-a-bitch. He’s going to be taken care of.”

Becker recalled Marcello inferring that, with the president out of the way, Bobby would lose all power as attorney general. Becker didn’t recall his exact words, but he told the committee that he thought Marcello was going to arrange the president’s murder in some way, possibly by getting someone outside of the Mafia to carry out the actual crime.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesCarlos Marcello testifies before the U.S. Senate Rackets Committee on September 7, 1961.

The committee also found that Carlos Marcello was tangentially linked to Dallas, where Kennedy was assassinated. Joseph Civello, a native of Baton Rouge, ran the smaller Dallas mob family under the aegis of Marcello. And feds traced calls from Civello to the Jefferson Music Company, one of the few places Marcello spoke on the phone.

The HSCA also took interest in Lee Harvey Oswald’s move to New Orleans in the spring and summer of 1963. They found that shortly before the assassination, Oswald lived with his uncle, a bookmaker in Marcello’s organization. Then there was Jack Ruby, who killed Lee Harvey Oswald two days after his arrest. Ruby ran the Carousel Club in Dallas, a drinking spot for area mobsters.

But in the end, the HSCA report reached no definitive conclusion about Marcello’s involvement, saying, “The committee found that Marcello had the motive, means and opportunity to have President John F. Kennedy assassinated, though it was unable to establish direct evidence of Marcello’s complicity.”

The government conducted a 40-year pursuit of Marcello. In 1982, at age 72, with the help of a cooperating informant, Marcello was sentenced to seven years for attempting to bribe officials in obtaining state insurance contracts. He received another ten years in a California bribery case, the sentences to run consecutively.

In 1989, Marcello’s conviction was overturned and he was released on good behavior. Carlos Marcello died in New Orleans in 1993, never again deported from the country.

But the shadowy world of Marcello left as many questions as answers upon his death. In fact, around this time, attorney Frank Ragano had recently published a book called Mob Lawyer about his time representing Marcello and his friend and colleague, Florida mob boss Santo Trafficante, for 30 years. And according to the book, Trafficante made an apparent deathbed confession just four days before he died in 1987:

“Carlos screwed up. We shouldn’t have killed John. We should’ve killed Bobby.”

After learning about the life and crimes of New Orleans mob boss Carlos Marcello, read the bloody story of Richard Kuklinski, the brutal Mafia hitman known as the “Iceman.” Then, learn the surprising story of mob boss Joseph Bonanno, who led one of New York’s largest crime families before retiring to write an autobiography.