Animal bone tubes uncovered at Chavín de Huántar were found to contain a mix of nicotine and vilca residue, a combination that would have produced terrifying and profound visions for those who snorted it some 2,800 years ago.

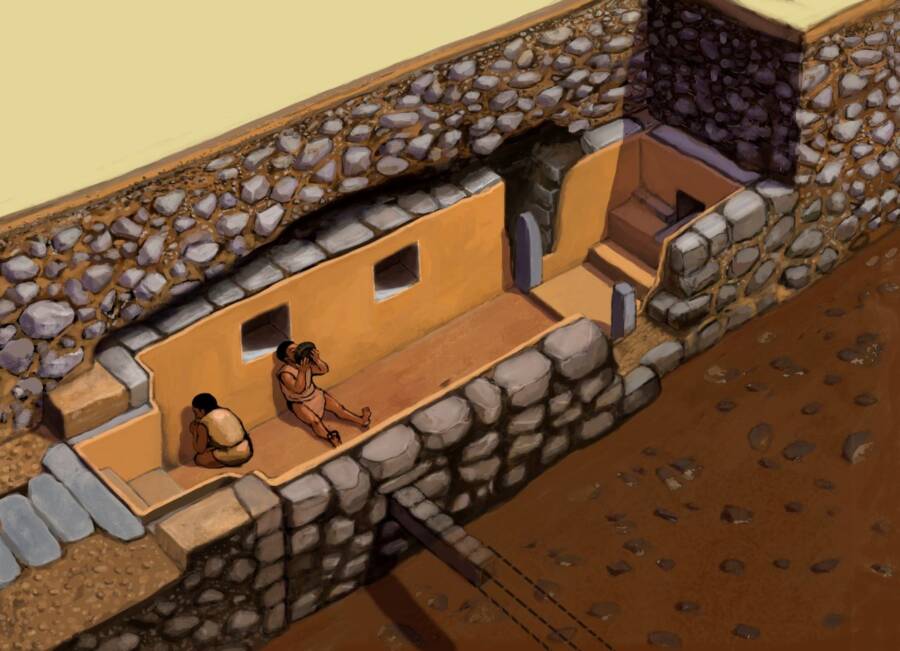

Daniel ContrerasAn artist’s render of the mysterious hallucinogenic chambers beneath Chavín de Huántar.

Archaeologists exploring the numerous underground chambers at the ancient Chavín de Huántar complex in Peru have found evidence of ritual practices involving hallucinogenic drugs, confirming long-held suspicions about the Chavín civilization’s ceremonial rituals.

The new discovery is the result of chemical analysis of the material found in cigarette-sized animal bone tubes unearthed at the site in 2017 and 2018. Results show that the tubes were stuffed with a combination of tobacco and a hallucinogenic plant known as vilca. Researchers believe these drug-fueled rituals may have helped the people of Chavín attain power and influence within their social hierarchy.

The results of their study were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences earlier this month.

The Chavín People Of Ancient Peru

Before the Inca civilization rose to prominence in Peru, the Andean highlands were dominated by a group known as the Chavín. Their society flourished for about 700 years between 900 and 200 B.C.E., and they are widely considered to be one of the earliest and most influential pre-Inca cultures in the region.

The center of their society was the ceremonial site of Chavín de Huántar, in the modern-day Ancash region of Peru. The site sits at an elevation of around 10,400 feet, is strategically positioned between the coast and the jungle, and once served as a major religious and cultural center. The complex itself is a feat of engineering, particularly the network of underground galleries and drainage systems that were designed to produce acoustic effects, such as mimicking the roar of a jaguar during ceremonies.

CyArk Chavin Database/Wikimedia CommonsA large circular plaza at Chavín de Huántar.

Based on archaeological examinations of the site and its structures, researchers determined that, like many pre-Columbian ancient societies, the Chavín worshiped a pantheon of deities that were often depicted as animal-human hybrids. However, the exact nature of the spiritual practices had long been the subject of speculation among researchers. It was clear that the complex’s underground chambers played a role, and historians theorized that hallucinogens were involved, but they had no concrete evidence to support this.

Now, they have found that proof.

The 2,800-Year-Old Drug Paraphernalia Found At Chavín De Huántar

The first clue came in 2017, when Stanford University archaeologist John Rick was excavating an underground chamber at Chavín de Huántar and his trowel struck something odd. When he picked it up to examine it, he noticed that the object was roughly the size of a cigarette and made of animal bone. It had also been packed full of sediment.

A year later, he and his team unearthed 20 similar objects. The artifacts were likely drug paraphernalia, Rick guessed, but more tests needed to be completed to confirm that suspicion.

Recently, a team of researchers from Stanford and the University of Florida worked to carry out a chemical analysis of the ancient tubes. According to a statement from the University of Florida, the analysis revealed traces of nicotine from the roots of plants related to tobacco as well as the residue of vilca beans, a hallucinogen related to DMT.

But this combination wasn’t smoked by just any ordinary person — it was reserved for a select few elite members of society.

Daniel ContrerasThe animal bone snuff tubes found within the underground chambers.

The snuff tubes were found in private chambers that could only have held a handful of people at a time. Unlike communal hallucinogens used in other cultures, the Chavín’s rituals were not meant to unify the masses — they were meant to control them.

“Taking psychoactives was not just about seeing visions. It was part of a tightly controlled ritual, likely reserved for a select few, reinforcing the social hierarchy,” said anthropological archaeologist Daniel Contreras, co-author of the study.

The snuff likely induced profound yet terrifying visions that would have been seen as a connection to some supernatural force.

“It probably took all kinds of knowledge and training to interpret what you were seeing,” archaeologist Jason Nesbitt told Science. “This isn’t people going off on a vision quest, or even a shaman taking some psychoactive substance in an individual ritual.”

Controlling access to this altered state, and therefore limiting the different interpretations of the visions, was a way for Chavín’s rulers to craft an ideology and convince their people that their leadership had been ordained by the divine. It was, they told the masses, the natural order of things that some should be held above others.

“One of the ways that inequality was justified or naturalized was through ideology — through the creation of impressive ceremonial experiences that made people believe this whole project was a good idea,” Contreras said.

Previous excavations at the site suggested that Chavín society marked a transition from the egalitarian civilizations that had preceded it and the empires that later came to dominate the Andean region. The complex at Chavín de Huántar may have also served as a pilgrimage site for the people who would go on to become the ruling classes of those empires.

And these hallucinogenic visions were at the center of that bid for power and control.

After reading about the ancient drug paraphernalia found in Peru, go inside the trippy history of peyote. Or, learn about the controversial history of absinthe.