Chief Joseph was determined not to abandon his ancestral lands and to stand his ground without violence. But the U.S. government had other ideas.

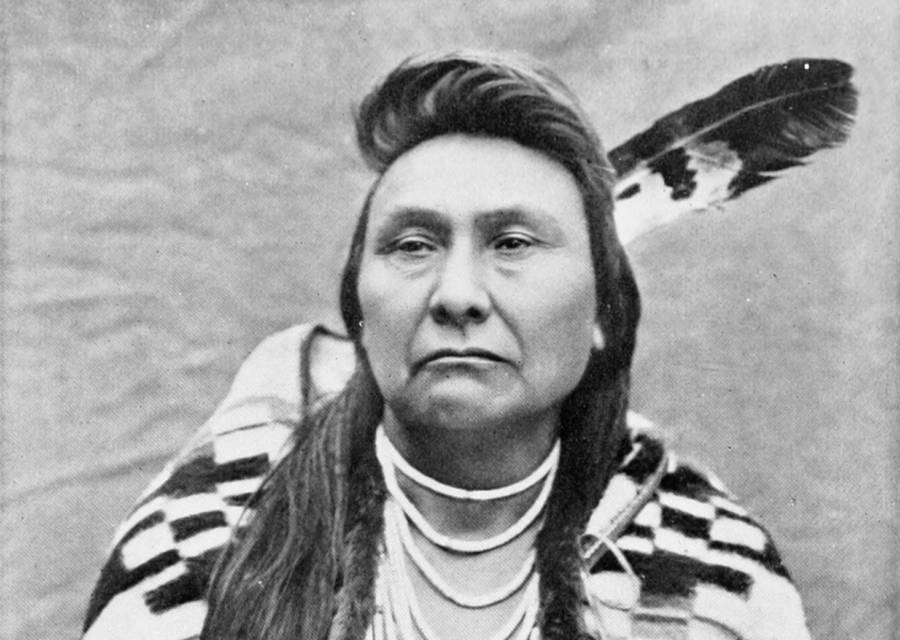

Wikimedia CommonsChief Joseph

Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce tribe in the Pacific Northwest was a warrior and a humanitarian who made it his life’s work to ensure the survival of his people’s land and heritage during the westward expansion of the United States. Throughout his life, he did just that, even coming to blows with the U.S. government over it.

But neither the government nor the threat of incarceration could break the resolve of Chief Joseph, who would go down in history for his bravery, perseverance, and love for his people.

A Legend Is Born

Chief Joseph, whose native name was Hinmatóowyalahtq̓it, was born in 1840 when his father Tuekakas, known as Old Joseph or Elder Joseph, was the leader of the Wal-lam-wat-kain (or Wallowa) tribe of Nez Perce Indians. The Wallowa tribe resided in the Pacific Northwest in an extensive plot of land in the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon.

Old Joseph had a history of trying to maintain cordial relations with white settlers and even converted to Christianity in 1838 and was baptized — when he received the name “Joseph.”

Around 1850, when Chief Joseph the younger was a boy, the Wallowa Valley began playing host to newcomers, a group of white settlers who had begun to move in from the north and the east, settling in the valley’s fruitful lands. Old Joseph was characteristically welcoming to the white settlers at first.

But before long, the settlers began to encroach ever further on the tribe’s land and demanded more space. When denied by Old Joseph, the settlers took it by force anyway and built farms and pastures for their livestock. As the settlers continued to move into native lands, tensions began to build. In an effort to make peace and create land boundaries, Isaac Stevens, governor of the Washington Territory, organized a council.

Under Stevens’ council, the 1855 Treaty of Walla Walla was drawn up. Signed by Old Joseph as well as the chiefs of the surrounding tribes, the treaty created a reservation encompassing more than 7 million acres of land for the various tribes – including the Wallowa Valley where the Wallowa tribe resided.

For the next eight years, the treaty seemed to have succeeded in maintaining a peaceful cohabitation between the Native American tribes and the white settlers. However, in 1863, a gold rush brought more settlers than the land could handle.

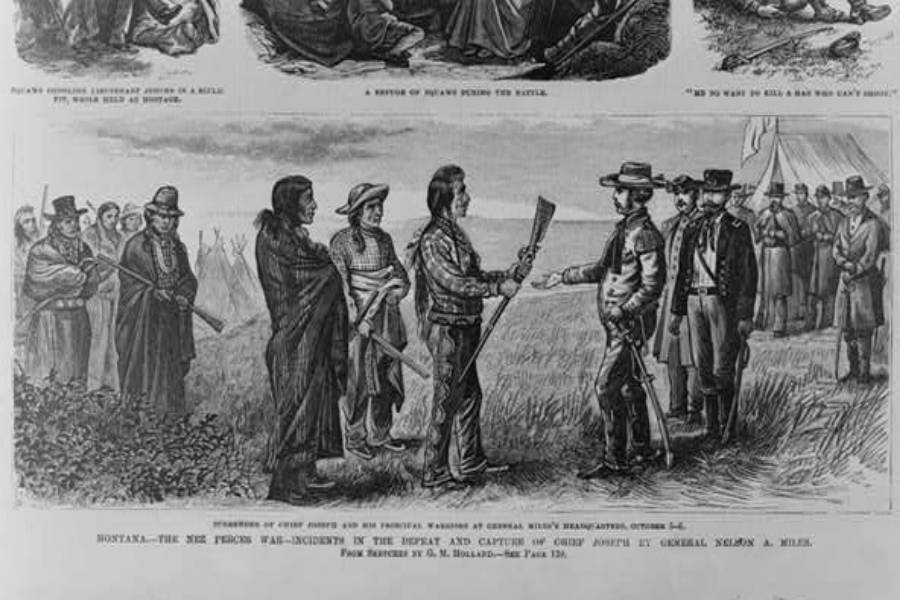

Wikimedia CommonsA cartoon depicting the meeting between the Nez Perce and the government envoy.

A second council was organized and a new treaty proposed, though this one was much more in favor of the white settlers. The treaty downgraded their previous 7-million-acre homeland to just over 700,000 acres. Worse yet was the fact that it excluded the Wallowa Valley entirely, and moved all of the tribes to western Idaho.

Several of the Nez Perce tribes agreed to the treaty and moved quickly. Old Joseph and a few others, however, declined to sign and stood their ground. Old Joseph broke ties literally and figuratively with the United States at that point: He threw away his Bible and burned his American flag.

Then, Old Joseph marked the Wallowa Valley with poles to outline their land and he declared: “Inside this boundary, all our people were born. It circles the graves of our fathers, and we will never give up these graves to any man.”

His words served as the fire that fueled his tribe and his son in the tumultuous decades to come.

Chief Joseph’s Non-Violent Stand

In 1871, before Old Joseph died, he counseled and prepared his son for the role of leader. In one recorded speech, he explained to his son the importance of the land, and his orders never to concede it to the settlers.

“When I am gone, think of your country… My son, never forget my dying words. This country holds your father’s body. Never sell the bones of your father and your mother.”

With those words, young Joseph became Chief Joseph and promised to uphold his father’s stance.

“A man who would not defend his father’s grave,” he said, “is worse than a wild beast.”

Chief Joseph’s reign would pick right up from the chaos that the end of his father’s leadership had left behind. While his father had forced a boundary and stood his ground, he had never faced quite as many settlers, among them greedy prospectors, as Chief Joseph now did.

Wikimedia CommonsChief Joseph

As the prospectors raided the Wallowa Valley and demanded land for farming and raising livestock, Chief Joseph came to verbal blows with them, made several concessions, and suffered through threats of violence and injustices against his people.

But he never allowed violence in retaliation for he feared the U.S. Government. Instead, the Nez Perce would simply stand their ground and intimidate the white settlers into leaving without violence.

In 1873, it seemed that the struggle was over at last. A new treaty was drawn up, once again, that ensured the safety of the Nez Perce’s home in the Wallowa Valley. Unfortunately, four years later the treaty was overturned, and the Native Americans were faced with a more formidable opponent: Army General Oliver O. Howard.

Wikimedia CommonsChief Joseph meets with a white settler in the Wallowa Valley.

General Howard had been granted permission to evict the Nez Perce from the Wallowa Valley this time with violence if they didn’t comply. Chief Joseph offered some parts of the land but not others in a compromise and offered that some Nez Perce leave but not all. He also attempted to reason with General Howard by telling him that he didn’t believe “the Great Spirit Chief gave one kind of men the right to tell another kind of men what they must do.”

In the end, though, Howard and Joseph couldn’t agree. In June of 1877, General Howard told Chief Joseph and two other band leaders within the Nex Perce tribe, White Bird, and Looking Glass, that their cordial negotiations were over and that from that day forward, the Army would consider any Nez Perce presence in the valley after 30 days an act of war.

Chief Joseph realized non-violence and peace were no longer options. Rather than face more bloodshed, he asked that his people to move quietly to the reservation.

The Nez Perce War

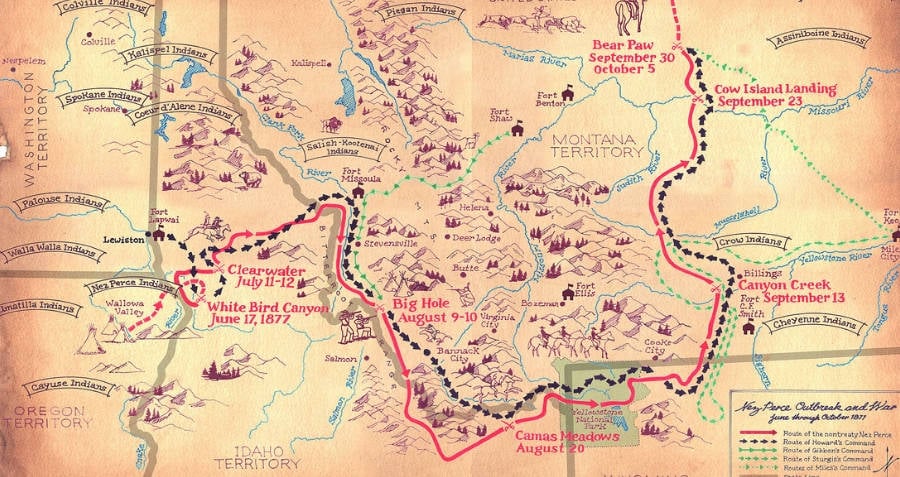

Wikimedia CommonsA map showing the migration and battle sights of the Nez Perce tribe.

Though his people did not actively participate in a physical battle, Chief Joseph was a key player in what would become known as the Nez Perce War. As other Nez Perce tribes clashed with General Howard’s army, Chief Joseph managed to herd his people out of the Wallowa Valley and into Idaho.

For more than 1,170 miles across present-day Oregon, Washington, Idaho, Wyoming, and Montana, Chief Joseph’s people successfully avoided the aggressive white pursuers.

His retreat has been remembered as a brilliant military maneuver, but in truth, it was a desperate attempt at a peaceful end to the violence facing his people. Only once was his tribe engaged in a full battle where they emerged victoriously – with 34 white soldiers killed and only three Nez Perce men wounded.

Eventually, unable to bear his people participating in violence, Chief Joseph sought an accord. He had lost more than 100 of his men and his people were hungry and tired. On Oct. 5, 1877, Chief Joseph conceded to Howard, with a speech that went down in history, and even gained the respect of several U.S. Army generals.

“I am tired of fighting. Our chiefs are killed…I want to have time to look for my children, to see how many I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever.”

Life For Chief Joseph After The Battle

Nez Perce tribal leaders Lean Elk, Looking Glass, and Joseph’s brother Ollokot were all killed in the final battles against the U.S. government.

Following his surrender, Chief Joseph and his people were carted away by rail car to Oklahoma where many of his people died from exposure to new diseases. But he continued to advocate for his people. Eventually, tired of discussing moving arrangements with generals, Chief Joseph traveled to Washington, D.C. to meet with President Rutherford B. Hayes.

It was not until 1885 that Joseph and other Nez Perce were returned to the Pacific Northwest, though half of them, including Joseph himself, were taken to a reservation in northern Washington that was not a part of their ancestral lands. They were thus separated from the rest of their people.

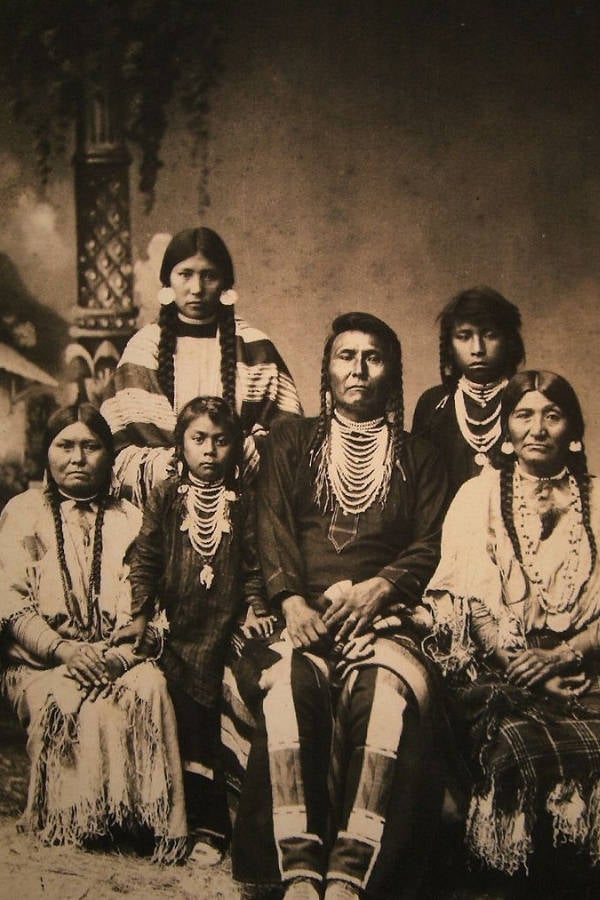

Wikimedia CommonsChief Joseph and his family.

For the next 30 years, Chief Joseph would continue to fight for his people’s homeland through speech and diplomacy, though never successfully. Finally, on Sept. 21, 1904, Chief Joseph died. His doctor claimed it was of a broken heart, and his people agreed.

Some blamed his peaceful tactics and claimed that had he fought harder or longer or used more violent tactics, he would have won — but his legacy disagrees. Where other chiefs fought for blood, Chief Joseph fought for peace and has thus remained a beacon of hope and an icon of non-violent resistance.

After this look at Chief Joseph, check out these stunning Edward Curtis photos that capture Native American culture in the early 20th century. Then, check out these amazing Native American masks.