The British Library's new project of digitizing children's books has led to the discovery of a 1480 text that reveals what was unacceptable for kids back then. Turns out, these rules hold true today.

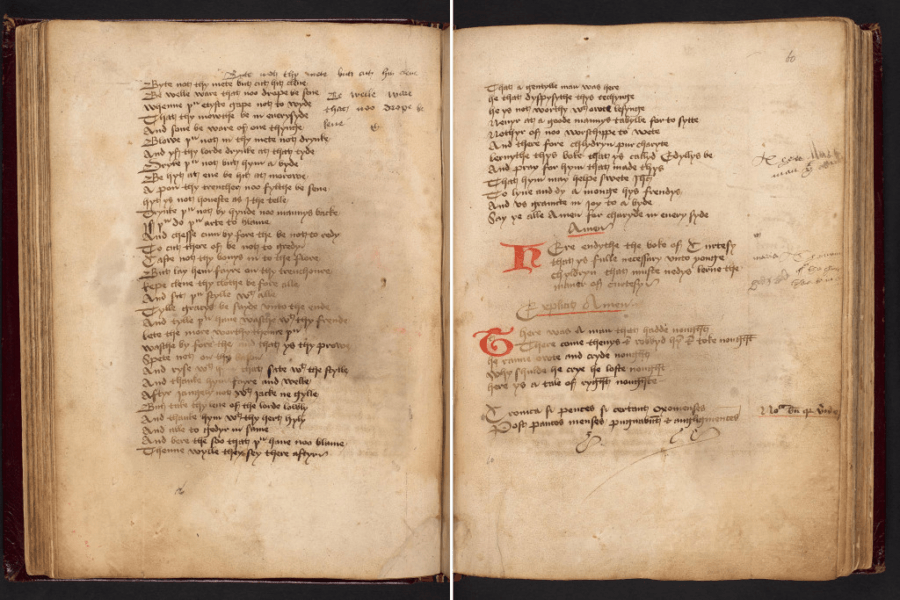

British LibraryThe manuscript was written in 1480 and aimed to help families refine their children’s social skills.

Nursery rhymes and fables have always aimed to teach children invaluable morals and life lessons, but this newly-unveiled 15th-century manuscript reveals just how similar the fundamental rules of children’s conduct 500 years ago are to today’s.

The British Library has just posted a digitized version of The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke online, revealing what was considered ill-behaved in the 15th century. The British Library’s new project intends to publish original manuscripts like these — as well as drafts and interviews with authors like Lewis Carroll — on their new children’s literature website.

As the library explained, “by listing all the many things that medieval children should not do, it also gives us a hint of the mischief they got up to.” A quick glance at some of the rules within show that respectable behavior hasn’t really change too much.

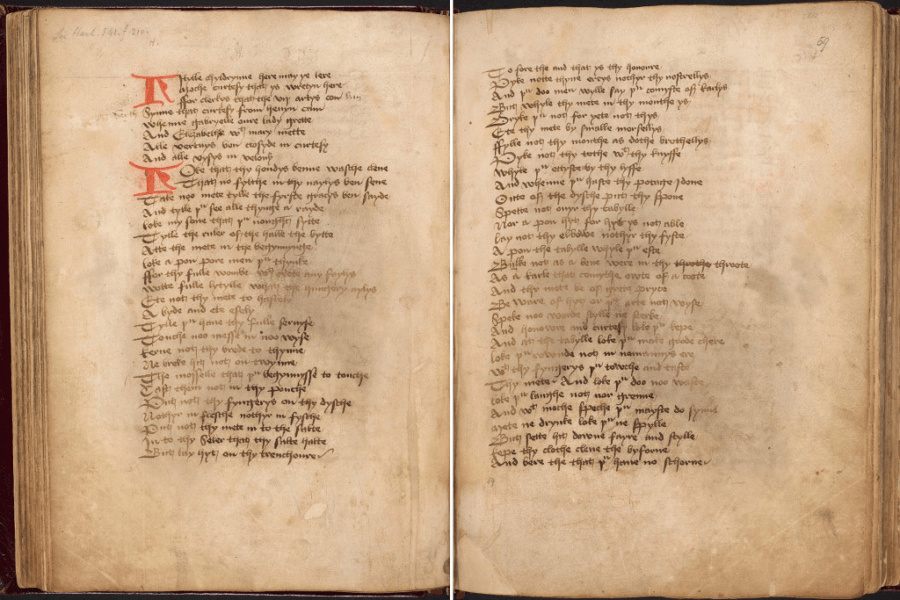

“Pyke notte thyne errys nothyr thy nostrellys” and “spette not ovyr thy tabylle” for instance, are two pieces of advice just as valuable today as they were in the 1400s. Chances are if you pick your nose or spit over the dinner table while on a date, there won’t be a second one.

So what exactly were the rules?

British LibraryFrom “don’t pick your nose” and “don’t spit over the table” to “don’t burp,” the advice in here is fairly timeless.

The Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke manuscript was meant to be what is known as a courtesy book. These were very popular across Europe from the 13th to 18th centuries, as people hoped their sophisticated manners and public behavior would help them climb the socioeconomic ladder.

For families wishing for better lives for their children, this kind of book might help them join noble families — or at least be considered for work at the royal court. The text also establishes how interlinked religion, manners, and social rank were at the time.

Here are some of the highlights from the text:

- “Pyke notte thyne errys nothyr thy nostrellys”: Don’t pick your ears or nose.

- “Pyke not thi tothe with thy knyffe”: Don’t pick your teeth with your knife.

- “Spette not ovyr thy tabylle”: Don’t spit over your table.

- “Bulle not as a bene were in thi throote”: Don’t burp as if you had a bean in your throat.

- “Loke thou laughe not, nor grenne / And with moche speche thou mayste do synne”: Don’t laugh, grin, or talk too much.

- “And yf thy Lorde drynke at that tyde / Dry[n]ke thou not, but hym abyde”: If your lord drinks, don’t drink. Wait until he’s finished.

- “And chesse cum by fore the, be not redy”: Don’t be greedy when they bring out the cheese.

Wikimedia CommonsThe courtesy book contains words spelled in a variety of ways, as the rules of Middle English had not yet been established. Only with William Caxton introducing printing to England (as seen above in Daniel Maclise’s painting), would spellings be agreed upon.

The manuscript’s author argued that “courtesy” stemmed directly from “heaven,” and that displaying ungraceful behavior was in opposition to God’s wishes. For Anne Lobbenberg who’s spearheading the library’s digital learning program as producer, the endeavor has been thoroughly insightful.

“These older collection items allow young people to examine the past close up,” she said. “Some of these sources will seem fascinatingly remote, while others may seem uncannily familiar despite being created hundreds of years ago.”

This particular text was clearly written in Middle English. Some of the words have since fallen by the wayside, while others used to denote different things entirely. “Meat,” for instance, was used to mean “food.” In terms of spelling, standardized rules were yet to be implemented.

The British Library has three different versions of the Lytille Childrenes Lytil Boke. This one included advice on hunting, carving meat, medicine, English kings, and blood-letting. Ultimately, it provides those of us living in the 21st century with both a familiar look and shocking whiplash at the past.

After learning about the 15th-century children’s etiquette book telling kids not to be greedy with the cheese or pick their noses, read about Psychopathia Sexualis, the 19th-century book experts used to explain sexual deviancy. Then, learn about the lost languages discovered in one of the world’s oldest libraries.