“The specific aim of the research program was to examine the possibility of controlling the behavior of a dog, in an open field, by means of remotely triggering electrical stimulation of the brain."

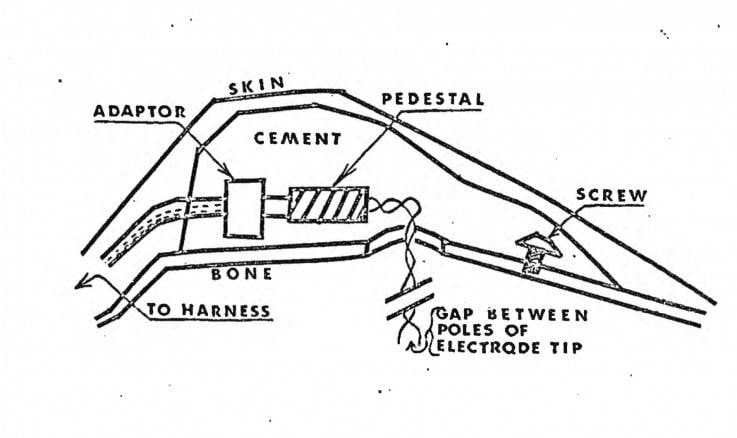

CIAA diagram of the electrode harness device used to control the dogs.

It’s been widely speculated that the CIA has dabbled in human mind control projects in the past, especially during the Cold War. But now, newly uncovered documents reveal that humans weren’t the only test subject of interest.

The infamous “behavior modification” (a.k.a. mind control) experiments carried out under the banner of Project MKUltra employed the likes of psychotropic drugs, electrical shocks, and radio waves to control human minds. However, the documents from 1967 now available thanks to the Freedom of Information Act paints a much broader picture of what the CIA was trying to accomplish with the notorious MKUltra.

According to Newsweek, the documents were handed over at the request of John Greenewald, founder of The Black Vault, a site specializing in declassified government records. And one letter reveals that animal mind control was not off the table at the CIA.

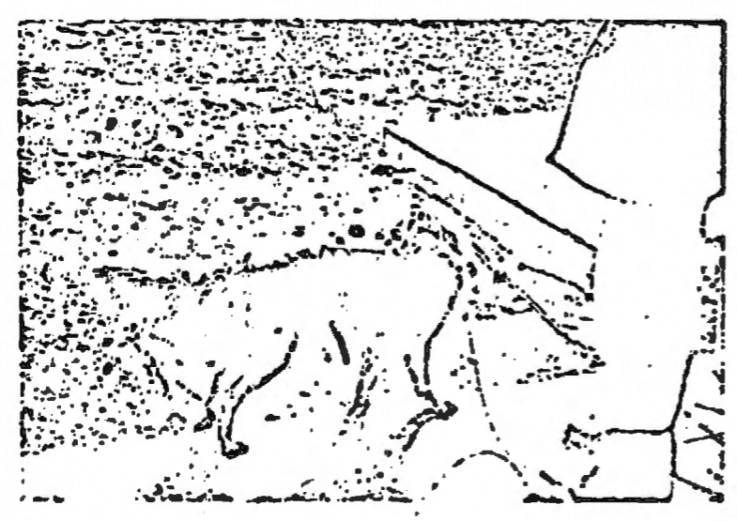

CIAA rendering of one of the six remote-controlled dogs.

The unidentified author of the letter stated that they had already created six remote-controlled dogs that had the ability to run, turn, and stop. Attached to the letter is a report that likewise states that the CIA undertook a project to hack into the minds of dogs and control their motor functions.

The report states:

“The specific aim of the research program was to examine the possibility of controlling the behavior of a dog, in an open field, by means of remotely triggering electrical stimulation of the brain.

“Such a system depends for its effectiveness on two properties of electrical stimulation delivered to certain deep lying structures of the dog brain: the well-known reward effect, and a tendency for such stimulation to initiate and maintain locomotion in a direction which is accompanied by the continued delivery of stimulation.”

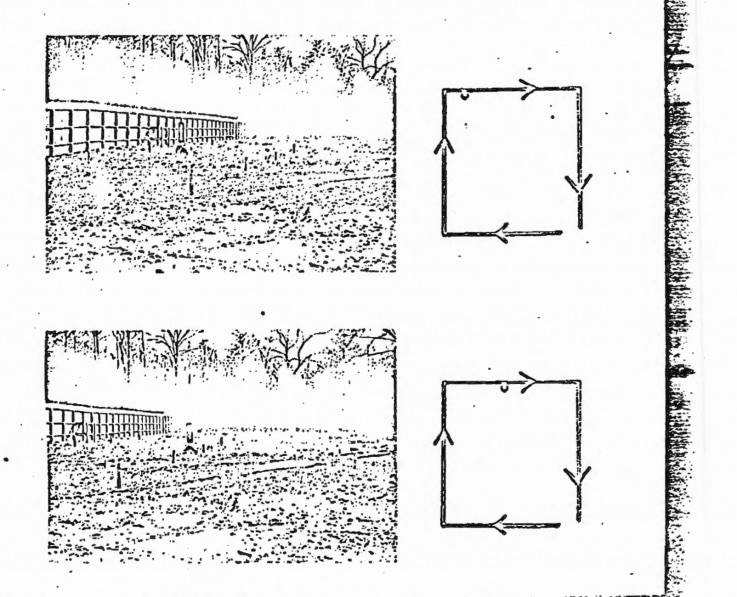

CIAThe patterns in which the remote-controlled dogs ran.

Furthermore, the report states that the CIA employed some pretty horrific methods in attempting to control the minds of dogs, one of which was described as follows: “embedding the electrode entirely within a mound of dental cement on the skull and running the leads subcutaneously to a point between the shoulder blades, where the leads are brought to the surface and affixed to a standard dog harness.”

This meant that dogs were forced to undergo surgery to have a device implanted into their brain that would then control their basic motor functions through the use of remote control and electric shock wave signaling.

“The stimulator had to be reliable and capable of sufficient voltage output to be usable in the face of expected impedance variation across individual dogs,” the report stated.

The CIA actually had some success with this project. The same report states that “behavioral control was limited to distances of 100 to 200 yards, at most.”

These remote-controlled dogs never wound up being used in actual field operations, however, at least from what these documents indicate. There were a lot of issues that got in the way of making remote-controlled dog operatives a reality.

Officials couldn’t find a space large enough to test the full capabilities of these dogs and the wounds that the dogs suffered from when they effectively underwent brain surgery hindered their performance as well.

And what the CIA wanted to do with these mind-controlled dogs had their experimentation been fully successful likewise remains unclear.

Next, learn about Soviet scientist Vladimir Demikhov’s creation of a two-headed dog during the Cold War. Then, read about how the CIA tried to use cats to spy on the Soviet Union.