On December 7, 43 B.C.E., Roman orator Marcus Tullius Cicero was murdered on the orders of Mark Antony — but his ideas didn't die with him.

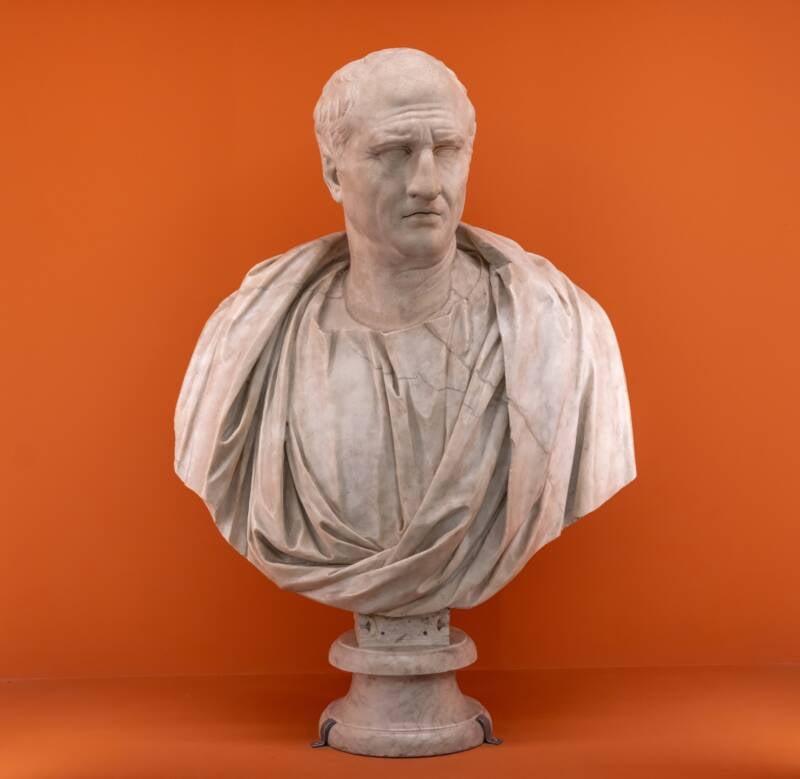

Wikimedia CommonsA bust of Cicero at the Musei Capitolini in Rome.

“If we are not ashamed to think it, we should not be ashamed to say it.”

So said Marcus Tullius Cicero, the great Roman orator, philosopher, and writer. Though more than 2,000 years have passed since he walked the Earth, his words are often still cited for their wisdom and candor.

He helped introduce Greek philosophy to Roman culture and created a Latin vocabulary for philosophical concepts. His work, covering subjects such as rhetoric, politics, and ethics, would go on to influence Renaissance thinkers, Enlightenment philosophers, and the founding fathers of the United States.

To say Cicero was an influential figure would be an understatement, but unfortunately for him, influencing Western culture for over two millennia posthumously could never be a guarantee of safety. While he achieved great things during his life and helped lay the groundwork for modern thinking, Cicero was still just a man, with all of the risks that entails. Most detrimentally, it meant he could make enemies — powerful ones, at that.

Amidst his turbulent relationship with Julius Caesar, Cicero cast his support in favor of Pompey during the men’s civil war. In the unstable period after Caesar’s death, Cicero greatly opposed Mark Antony, believing he was a threat to the Roman Republic’s restoration and survival, and he encouraged the Roman Senate to support Antony’s rival Octavian instead.

Cicero’s gamble backfired. Octavian and Antony reconciled, along with Lepidus, to form the Second Triumvirate — and Antony demanded Cicero’s execution, never forgiving him for the propaganda. Thus, his fate was sealed.

Cicero’s Early Life, Education, And Rise To Power

Marcus Tullius Cicero was born on Jan. 3, 106 B.C.E., likely in the town of Arpinum, located to the southeast of Rome. Though his family was wealthy and part of the equestrian order, they had no strong ties to the senatorial elite. As such, Cicero was considered a novus homo, or “new man,” the first in his family to pursue the highest offices of the Roman Republic.

Public DomainThe Young Cicero Reading by Vincenzo Foppa (1464).

Gifted with an extraordinary intellect, he studied law, rhetoric, and philosophy under some of the most renowned teachers of his day, including Greek philosophers and rhetoricians. He immersed himself in these teachings and completed military service in 89 B.C.E. under Pompeius Strabo — the father of Pompey. In 81 B.C.E., Cicero established himself in the courts, but his first major case came about a year later.

Around 80 B.C.E., Cicero defended Sextus Roscius, who had been falsely accused of parricide. In taking on the case, Cicero also challenged allies of the dictator Sulla, while ensuring he didn’t directly implicate Sulla himself.

Cicero’s successful defense was a display of his courage and gift for argument, cementing his reputation as a promising speaker.

Over the next decade, Cicero rose through the cursus honorum, the sequence of public offices pursued by ambitious Romans. His prosecution of Gaius Verres, the corrupt governor of Sicily, in 70 B.C.E. brought him even more acclaim. Verres had plundered Sicily and mistreated its people, and Cicero’s orations against him helped expose his corrupt actions and poor character, eventually leading him into exile. Cicero said:

“Since the whole of our poorer class is being oppressed by the hand of recklessness and crime, and groaning under the infamy of our law-courts, I declare myself to these criminals as their enemy and their accuser, as their pertinacious, bitter, and unrelenting adversary… I here issue this warning, this public notice, this preliminary proclamation: To all those who are in the habit of depositing or receiving deposits for bribery, of undertaking to offer or offering bribes, or of acting as agents or go-betweens for the corruption of judges in our courts, and to all those who have offered to make use of their power or their shamelessness for these purposes: in this present trial, take care that your hands and your minds are kept clear of this vile crime.”

Through cases like this, Cicero endeared himself to the citizens of Rome. After some time, this paved his way to the consulship.

Consulship And The Catiline Conspiracy

Public DomainCicero Denounces Catiline by Cesare Maccari.

In 63 B.C.E., Cicero was elected as consul, the highest of the ordinary magistracies in Rome. His election was a triumph for a novus homo and testified to his popularity. His consulship, however, coincided with one of the most dramatic periods of the late Republic: the Catiline Conspiracy.

Lucius Sergius Catilina, or Catiline, was a patrician burdened by debts and frustrated by politics. He assembled a coalition of impoverished nobles, veterans, and desperate debtors to seize power by force, promising debt cancellation and a radical break from the political order.

When the growing plot to overthrow the Roman Republic ultimately came to light, Cicero famously denounced Catiline in the Senate:

“When, O Catiline, do you mean to cease abusing our patience? How long is that madness of yours still to mock us? When is there to be an end of that unbridled audacity of yours, swaggering about as it does now? … Do you not feel that your plans are detected? Do you not see that your conspiracy is already arrested and rendered powerless by the knowledge which everyone here possesses of it?”

Over the course of his four Catilinarian Orations, Cicero rallied senators and exposed the growing conspiracy, forcing Catiline to flee the city. Catiline’s fellow conspirators in Rome were captured, and Cicero, faced with the Senate’s indecision over their fate, authorized their execution.

The people of Rome celebrated Cicero for his decision, hailing him as pater patriae, the “father of his country.” But this veneration was not universal. Some critics accused Cicero of violating the rights of Roman citizens, since he put the revolutionaries to death without a trial, and as he later fell out of favor among political elites, the decision became a weapon for his enemies.

Exile, Return, And The Civil Wars

In the years following the conspiracy, Cicero’s fortunes shifted greatly. The rise of the First Triumvirate — Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus — reshaped Roman politics, and Cicero, while still widely respected, was mostly sidelined as a result. In 58 B.C.E., his rival Publius Clodius Pulcher, serving as tribune of the people, passed a law targeting anyone who had executed citizens without trial. His intention in doing so was not subtle.

Cicero was soon forced into exile. His house was destroyed, his property was confiscated, and he wandered Greece in despair.

Around a year later, popular demand and the intercession of Pompey secured his recall. He returned to Rome in 57 B.C.E. to a hero’s welcome, but his political influence was weakened at that point. From then on, he increasingly retreated from direct politics, focusing instead on his writing and philosophical reflection. He never fully abandoned public life, though.

Public DomainCicero at His Villa at Tusculum by J.M.W. Turner.

As the Republic fell into greater instability throughout the 50s B.C.E., Caesar continued to amass power in Gaul. His eventual crossing of the Rubicon in 49 B.C.E. plunged Rome into civil war. Cicero initially hesitated, but ultimately sided with Pompey and the senatorial caucus against Caesar.

Pompey was subsequently defeated at Pharsalus, prompting Cicero to once again return to Rome. In a surprising gesture of respect, however, Caesar pardoned him, allowing him to live in relative safety.

Caesar’s dictatorship still angered Cicero, however, and he largely withdrew from politics and dove back into his writings. During this time, he produced many influential works, such as the Brutus, Paradoxa Stoicorum (Paradoxes of the Stoics), and Tusculanae disputationes (Tusculan Disputations).

Meanwhile, he helped preserve Greek philosophy, using his skills as a translator to make it accessible to Latin leaders, which would later lead to him influencing Western philosophy for centuries.

But as he tirelessly worked, the future of Rome once again became uncertain. Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C.E.

The Assassination Of Caesar And The Philippics

Wikimedia CommonsThe Death of Julius Caesar by Vincenzo Camuccini (Circa 1804).

Caesar’s death marked a major turning point in Rome’s history — though not, perhaps, in the ways that many had hoped. Cicero initially took the dictator’s death as a sign that the Roman Republic might be restored.

“Our tyrant deserved his death for having made an exception of the one thing that was the blackest crime of all,” Cicero later wrote of Caesar’s assassination. “…here you have a man who was ambitious to be king of the Roman People and master of the whole world; and he achieved it! The man who maintains that such an ambition is morally right is a madman…”

But he soon realized that Caesar’s death created more chaos than stability.

Cicero was particularly worried about the influence of Mark Antony, who, as consul, positioned himself as Caesar’s political heir, while Caesar’s adopted son Octavian entered the fray. Cicero placed his faith in Octavian — a move met with criticism by one of Caesar’s assassins, Marcus Junius Brutus.

Wikimedia CommonsThe Death of Caesar by Jean-Léon Gérôme.

“Upon my honor I do not think that all the gods are so hostile to the safety of the Roman people, that we need entreat Octavius for the safety of any citizen…” Brutus wrote in a letter to Cicero.

He continued later in the letter, “…if we had remembered that we were Romans, these dregs of mankind would not have conceived the ambition of playing the tyrant with more boldness than we should have forbidden it: nor would Antony have had his ambition more roused by Caesar’s royalty, than his fears excited by Caesar’s death.”

Still, Cicero had placed his bet. And starting in September 44 B.C.E., he launched a blistering series of 14 speeches, known as the Philippics, modeled after Demosthenes’ attacks on Philip of Macedon. In these, Cicero accused Antony of corruption, tyranny, and debauchery, painting him as an enemy of the Roman Republic. It was a fatal miscalculation.

Cicero’s Death On The Orders Of Mark Antony

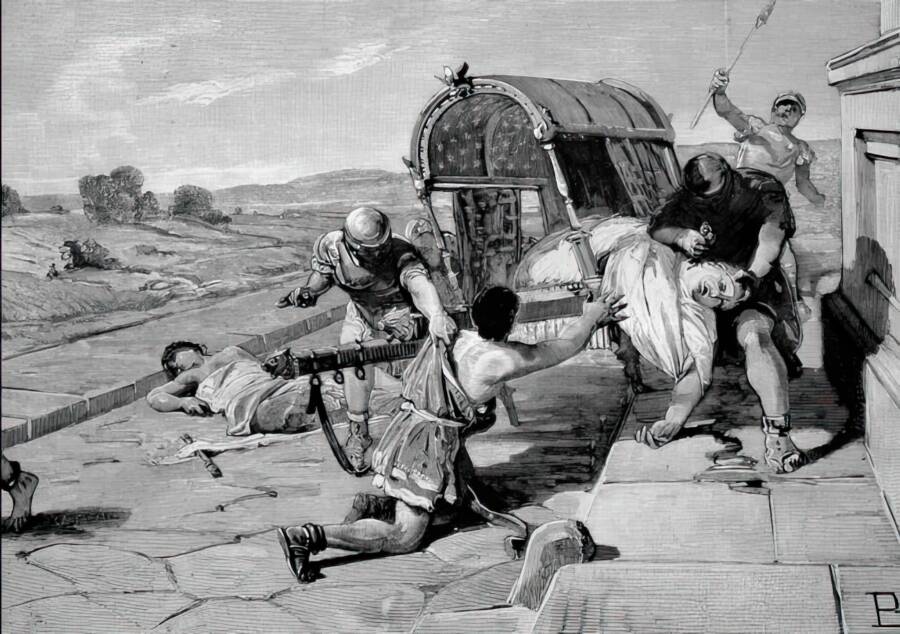

Wikimedia CommonsA 19th-century depiction of Cicero being captured and murdered at age 63.

Cicero had put all his energy into persuading the Senate to oppose Antony, but Octavian eventually allied with Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate. Antony, unlike Caesar, never forgave Cicero for the Philippics and demanded his death soon after forming the alliance.

In 43 B.C.E., Cicero attempted to flee Rome, but was captured by Antony’s men near Formiae on December 7th. Accounts of his final moments differ, but it’s been said that Cicero accepted his fate once he realized he could not escape. He reportedly told his executioner, “I go no further: approach, veteran soldier, and, if you can at least do so much properly, sever this neck.”

Indeed, Cicero was not only beheaded by the men, but his hands were also cut off, purportedly due to the soldiers’ anger that Cicero had once used his hands to write statements against Antony.

Public DomainThe Vengeance Of Fulvia by Maura y Montaner, depicting Mark Antony’s wife Fulvia examining Cicero’s severed head.

Antony’s soldiers presented him with Cicero’s head, after which Antony displayed Cicero’s head on the rostra, the speakers’ platform at the Forum in Rome. The gruesome exhibit also included Cicero’s severed hands. Perhaps the only person happier than Antony to see Cicero’s head was Antony’s then-wife Fulvia, who reportedly pierced his tongue with her hairpins.

With that, the last great voice of the Roman Republic was silenced.

Cicero once wrote: “The welfare of the people is the ultimate law.” However, during his time, that core principle was crushed under the weight of civil war, deadly power struggles, and dictatorship. But even though Cicero could no longer speak or write, his words lived on and continued to inspire generations far beyond the ruins of the Roman Republic.

After reading about the Roman orator Cicero, read about the tragic death of Antinous, the gay lover of Roman Emperor Hadrian. Then, learn about Pontius Pilate, the Roman governor who ordered Jesus’ crucifixion.