From his love affair with Cleopatra to his humiliating defeat by Octavian, Mark Antony left behind a memorable — and complicated — legacy.

Lanmas/Alamy Stock PhotoMark Antony was a Roman politician and general who played a pivotal role in the final years of the Roman Republic.

History is rife with tragic love stories, but few have the lasting impact of the story of Cleopatra and Mark Antony. While their relationship carried political weight, it was also romantic — and much like Romeo and Juliet, their love story ended with the two lovers taking their own lives.

But beyond his romance with Cleopatra, Mark Antony was also one of ancient Rome’s most influential figures. Following the assassination of Julius Caesar, Antony established himself as one of the most pivotal leaders in the final years of the Roman Republic, before it became the Roman Empire. However, his uneasy alliance with Octavian soon turned into a bitter rivalry, which eventually culminated in open conflict and the Battle of Actium. Unfortunately for Antony, Octavian’s forces emerged victorious.

Antony’s defeat and suicide ultimately paved the way for Octavian to ascend to the Roman throne as the emperor Augustus, fundamentally changing the course of history forever. Still, the ill-fated romance of Mark Antony and Cleopatra resonates strongly today, as evidenced by various adaptations of their story and the clear influence it had on famous works of fiction.

Mark Antony’s Early Life And Rise To Prominence

Born on Jan. 14, 83 B.C.E., Marcus Antonius, now known as Mark Antony, hailed from a respected Roman family. His father, Marcus Antonius Creticus, was a supporter of the populist politician Marius. After his father’s early death, Antony was primarily raised by his mother, Julia Antonia.

He showed great promise in his early years, but he also fell victim to the temptations of his young mind and regularly engaged in reckless behavior, especially when he became friends with Pubilius Clodius Pulcher and Curio. As the Greek writer and philosopher Plutarch chronicled:

“Antony gave brilliant promise in his youth, they say, until his intimate friendship with Curio fell upon him like a pest. For Curio himself was unrestrained in his pleasures, and in order to make Antony more manageable, engaged him in drinking bouts, and with women, and in immoderate and extravagant expenditures. This involved Antony in a heavy debt and one that was excessive for his years — a debt of two hundred and fifty talents.”

That debt of 250 talents would be equivalent to more than $5 million today — a significant debt, regardless of the time period or place.

Classic Image/Alamy Stock PhotoMark Antony was a talented general, but he also had a reputation for engaging in heavy drinking and promiscuity.

As he entered adulthood, Mark Antony pursued a military career, serving under Aulus Gabinius in various campaigns and expeditions as a commander of cavalry. Eventually, sometime around 54 B.C.E., Antony became a close ally of Julius Caesar, to whom he was related via his mother’s side. Antony served alongside Caesar, notably during Caesar’s conquest of Gaul.

This close allegiance followed the two men into the civil war that happened after that, when Pompey’s forces fought against Caesar’s. Antony offered Caesar his unwavering support and even fought in the campaign that forced Pompey to withdraw from the Italian peninsula — a move that impressed Caesar. In fact, Caesar’s faith in Antony was so strong that when he left for his Spanish campaign, he charged Antony with overseeing Italy.

After Caesar’s return, Antony became consul as colleague and a flamen, or priest, of Caesar. Antony was even the one to present Caesar with a diadem — a ribbon to symbolize royalty — at the festival of the Lupercalia. Caesar, however, did not accept the offering, sensing the people’s disdain for a monarch. Fatefully, Caesar would still crown himself “dictator in perpetuity.”

Not long after that, in 44 B.C.E., Julius Caesar was assassinated by the Roman Senate — and the future of Rome was suddenly uncertain.

Mark Antony’s Growing Rivalry With Octavian And The Second Triumvirate

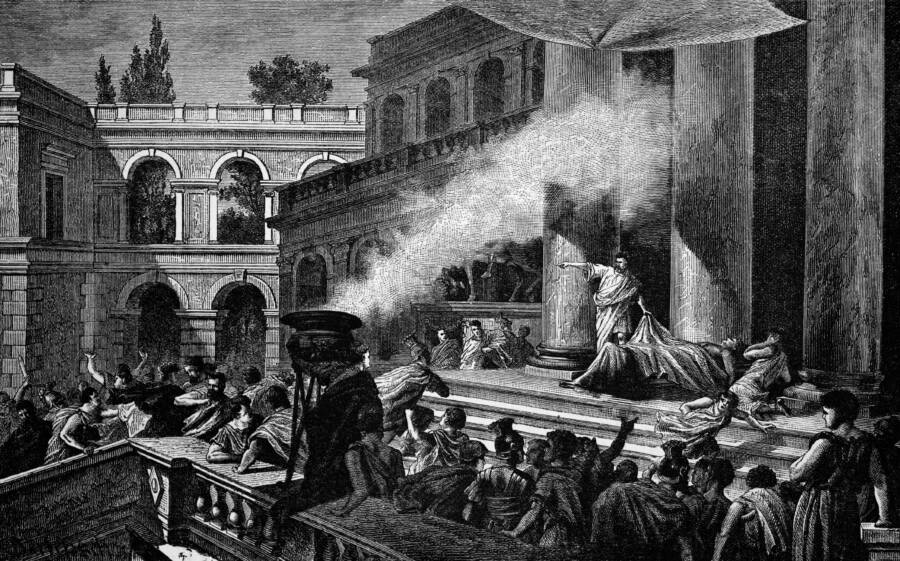

De Luan/Alamy Stock PhotoMark Antony showing the body of Julius Caesar after his assassination in 44 B.C.E.

Following Julius Caesar’s assassination, both Mark Antony and Octavian sought to position themselves as his political heirs. Antony gained possession of the Roman treasury and Caesar’s papers and initially pushed relatively moderate policies — though the transition was far from smooth.

In 43 B.C.E., Octavian made a move against Antony, joining forces with consuls and defeating Antony’s forces twice, forcing him to withdraw into southern Gaul. When the consuls died, their armies ended up breaking up.

Antony, meanwhile, was joined by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus and Lucius Munatius Plancus and their armies. In November of that year, Octavian, Antony, and Lepidus met in Bononia (located in modern-day Bologna) to discuss their conflict. They ultimately agreed to a five-year pact that would enter them into a joint autocracy known as the Second Triumvirate. Interestingly, the First Triumvirate had once included Caesar and Pompey.

Together, the Second Triumvirate consolidated their power to defeat Caesar’s assassins and opponents, but tensions were brewing among the men in the meantime. Antony viewed Octavian as inexperienced, and the two men had very different visions for the future of Rome. Factoring in their own personal ambitions, the stage was set for even more conflict.

Still, they had agreed to split control of the empire, with Antony taking charge of the eastern provinces. Antony sought to root out anyone in his territory who would aid his enemies, and so, following up on rumors that one leader had done so, he summoned the Egyptian queen Cleopatra to meet him in Tarsus in Anatolia (located in modern-day Türkiye) in 41 B.C.E.

But Antony was bewitched by Cleopatra’s charms, and the two became lovers, setting in motion one of the greatest tragic romances in history.

An Ill-Fated Romance With Cleopatra

Public DomainDepictions of Cleopatra (left) and Mark Antony (right) on two sides of an ancient coin.

Mark Antony fell for Cleopatra shortly after their meeting in 41 B.C.E. At the time, Cleopatra was seeking a close alliance to secure her throne and Egypt’s independence. So it’s no accident that she arrived in a grand display, presenting herself as the human embodiment of the goddess Aphrodite.

As the American author Stacy Schiff writes in Cleopatra: A Life, “She reclined beneath a gold-spangled canopy, dressed as Venus in a painting, while beautiful young boys, like painted Cupids, stood at her sides and fanned her. Her fairest maids were likewise dressed as sea nymphs and graces, some steering at the rudder, some working at the ropes. Wondrous odors from countless incense-offerings diffused themselves along the river-banks.”

Peter Horree/Alamy Stock PhotoThe arrival of Cleopatra in Tarsus, where she met with Mark Antony.

Antony and Cleopatra quickly became lovers, and by 40 B.C.E., Cleopatra had already given birth to the couple’s twins: Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II. But Antony didn’t meet his new children right away, as he had returned to Rome for another three years before reuniting with Cleopatra.

In the meantime, however, Mark Antony continued to increase Cleopatra’s territorial possessions, allowing her to retain Egypt’s independence and meet her other political goals. Egypt likewise provided Antony with enough wealth to fund his military campaigns, particularly against Parthia.

Shortly after Antony returned from seeing Cleopatra in Alexandria, Egypt, the consul Lucius Antonius rebelled against Octavian in Italy — with support from Antony’s then-wife, Fulvia. Octavian quickly squashed the rebellion, and after a few small skirmishes, he and Antony eventually reconciled at Brundisium. Fulvia, meanwhile, had died, opening Antony up to a new union. But it was not Cleopatra who would become Antony’s next wife.

Rather, it was Octavian’s sister, Octavia, who married Antony in 40 B.C.E., once again securing an uneasy alliance between the two men (despite Cleopatra giving birth to Antony’s babies that same year). Once again, control of Rome would be split — Antony ruling the east, Octavian ruling the west.

When Antony attacked Parthia in 36 B.C.E., however, this alliance proved fruitless. He suffered an embarrassing defeat — the first major military defeat of his career — and he turned once again to Cleopatra. Unfortunately, this time, Octavian would use their relationship to his own advantage.

How Rumors Of Cleopatra’s Death Led Mark Antony To Take His Own Life

20th Century Fox/Wikimedia CommonsMark Antony and Cleopatra’s doomed romance has been dramatized countless times, including in the famous 1963 movie Cleopatra, starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

Having sent Octavia away when she came to meet him with troops in 35 B.C.E., Mark Antony then launched a more successful military campaign in Armenia. He eventually annexed it to Rome. However, it was not Rome he would return to for his celebration. Antony chose, instead, to celebrate his victory in Alexandria with Cleopatra by his side. He then formally ceded several Roman territories to Cleopatra and their young children. He also declared Cleopatra’s eldest son Caesarion, who was thought to have been fathered by Julius Caesar, the legitimate heir to Caesar’s throne.

Clearly, Antony and Cleopatra wanted to make sure that all of Cleopatra’s children (including Ptolemy Philadelphus, another son fathered by Antony) had as much power as possible. But by uplifting Caesarion, they also made a public challenge to Octavian’s claim that he was the true heir.

Wikimedia CommonsOctavian, also known as Augustus, the first emperor of the Roman Empire.

Octavian was enraged by Antony’s continued political and romantic alliance with Cleopatra, especially since Antony had left Octavian’s sister for Cleopatra. So he worked quickly to discredit Antony. Octavian launched a propaganda campaign against his rival, reading a troubling document in the Senate that was supposedly Antony’s will. Furthermore, Octavian claimed that Antony and Cleopatra were making preparations to take over Rome.

Shortly after Antony officially divorced Octavia, Octavian dropped any remaining alliance he had with Antony and declared war — not against Antony, but against Cleopatra, as Octavian knew that some members of the Senate would be hesitant to go up against Antony directly.

Antony and Cleopatra’s forces met Octavian’s powerful army at the Battle of Actium in 31 B.C.E. In the end, Octavian’s General Agrippa ultimately defeated Antony and Cleopatra’s troops. However, this prompted a series of smaller skirmishes that would pull Antony further away from Cleopatra.

This distance allowed a rumor to reach Antony in 30 B.C.E.: Cleopatra, he was told, was dead. Upon hearing this, Antony was so distraught that he stabbed himself with his own sword and was brought dying, to his surprise, to a still-alive Cleopatra. He died in her arms, and shortly after that, Cleopatra took her own life, purportedly with the help of a venomous snake.

incamerastock/Alamy Stock PhotoA depiction of Mark Antony dying in the arms of Cleopatra.

Octavian, having eliminated his rivals, saw to it that no one else could challenge his claim to the throne. He had Caesarion executed, then paraded Cleopatra’s children Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II in Rome near an effigy of their dead mother. (Ptolemy Philadelphus’ fate remains unknown, but many believe he died after he was taken captive by the Romans.) After the humiliating parade, Octavian decided to spare Cleopatra Selene II and Alexander Helios, leaving them in the care of his sister, Octavia.

And finally, in 27 B.C.E., Octavian was given the new name Augustus and became the very first emperor of the Roman Empire.

After learning about Mark Antony, read about the search for Cleopatra’s tomb. Then, go inside the stories of the worst Roman emperors.