Clyde Tombaugh's legacy hinges on his discovery of Pluto. But both before and after that moment, his story is extraordinary. Meet the man behind Pluto.

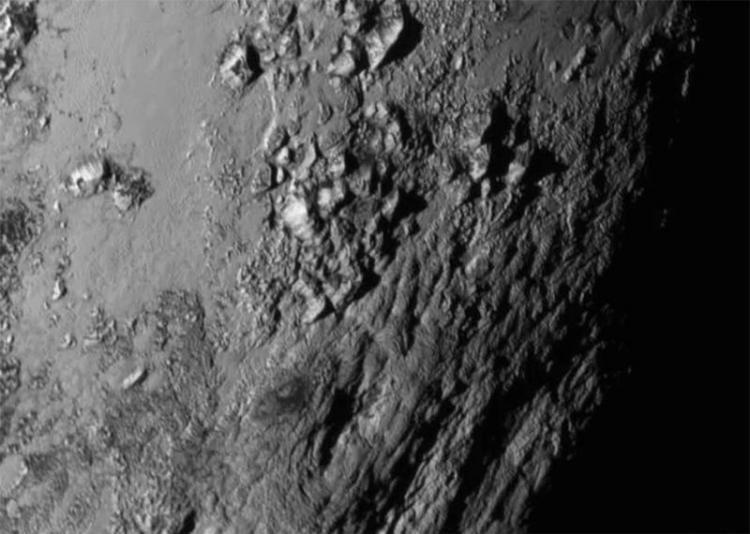

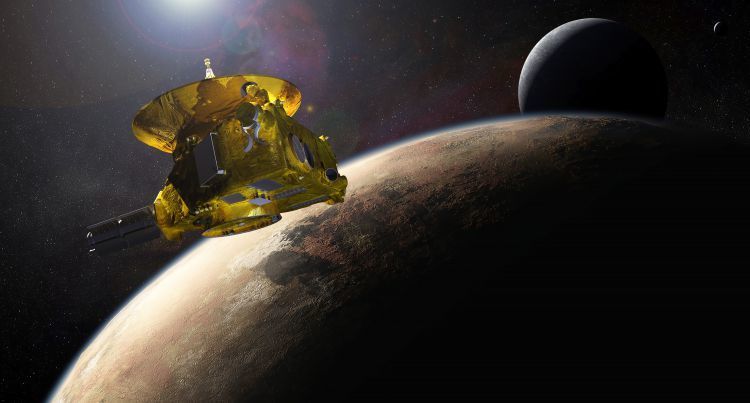

Recent New Horizons photo of Pluto’s icy mountains. Source: NASA

Beyond the rocky planets neighboring Earth and both the outlying gas and ice giants, sits the dark and icy dwarf planet, Pluto.

Until July 14th of this year, when the New Horizons spacecraft made the closest-ever flyby, Pluto had never truly been explored. It was out of reach, nestled deep in the third zone of our solar system, the Kuiper Belt, a circling mass of frozen, asteroid-like objects whose inner edge is about 2.8 billion miles from the sun.

Until now, our perception of the dwarf planet has been shrouded mostly in mystery.

The New Hoirzons spacecraft launches from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on January 19, 2006. Source: Forbes

Yet there is one man aboard New Horizons without whom we wouldn’t be here at all.

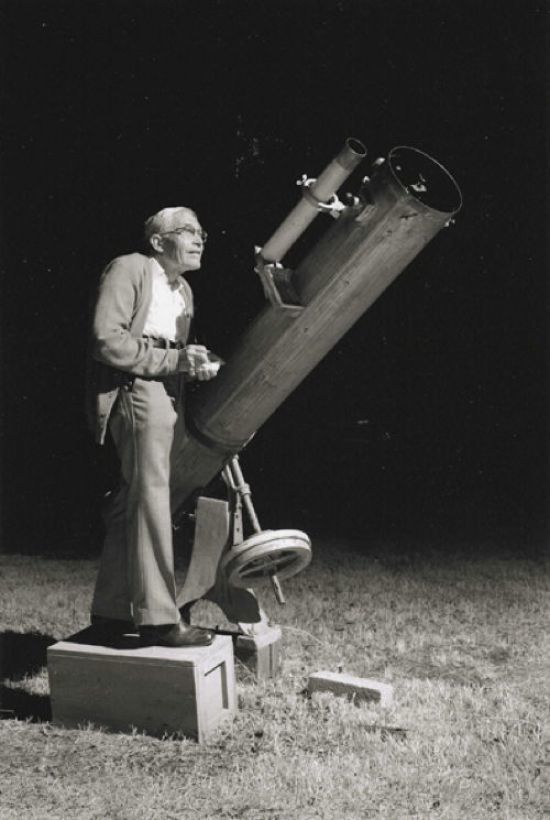

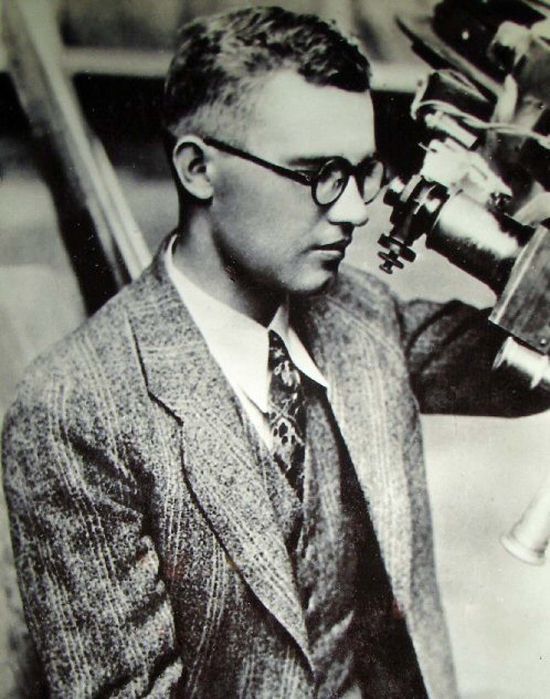

Clyde Tombaugh. Source: Blogspot

On February 18, 1930, at only 24 years of age, Clyde Tombaugh made a historic discovery. A young astronomer fascinated with the stars, Tombaugh found what was then believed to be the 9th planet of our solar system.

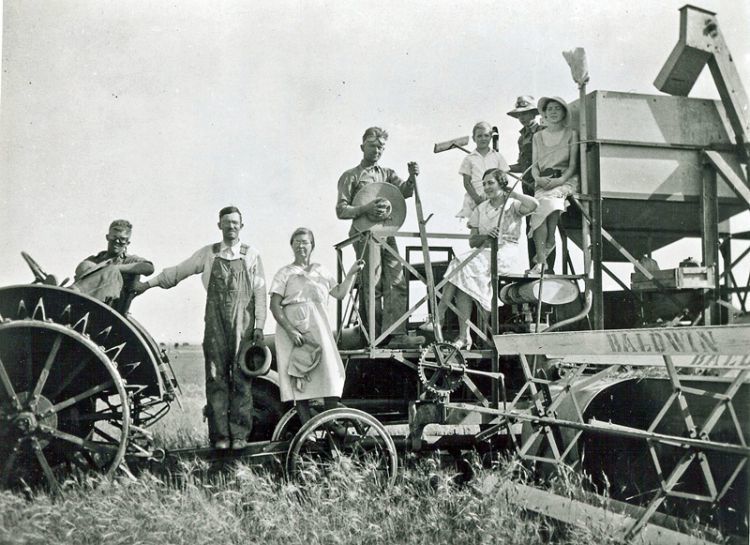

Clyde Tombaugh (second from left) with his family at their farm in Kansas in 1935, five years after his discovery of Pluto. Source: Slashgear

Coming from humble beginnings, Tombaugh didn’t always have such good luck. Born and raised in Streator, Illinois, his family packed up and headed to Kansas in hopes of nurturing a bountiful farm. After the move, however, a terrible hailstorm ruined most of the crops, eradicating any hopes Tombaugh had for attending college.

Despite his family’s economic turmoil, Tombaugh continued to study on his own. Geometry and trigonometry became his afternoon delight. But it was after peering at the night sky through his uncle’s telescope that Tombaugh knew what he wanted to do with his life.

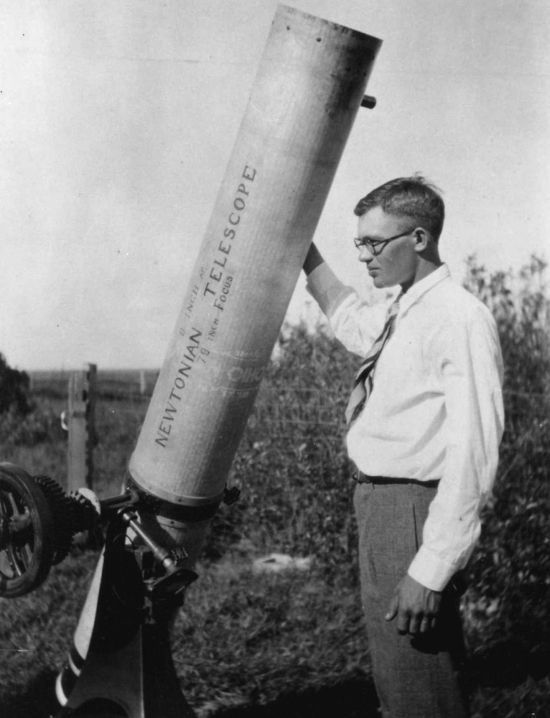

At 20 years old, Tombaugh built his first telescope. But he wasn’t satisfied. He built one or two more, using makeshift parts from around the farm, anything he could get his hands on–even a crankshaft made from a 1910 Buick.

Source: Popular Science

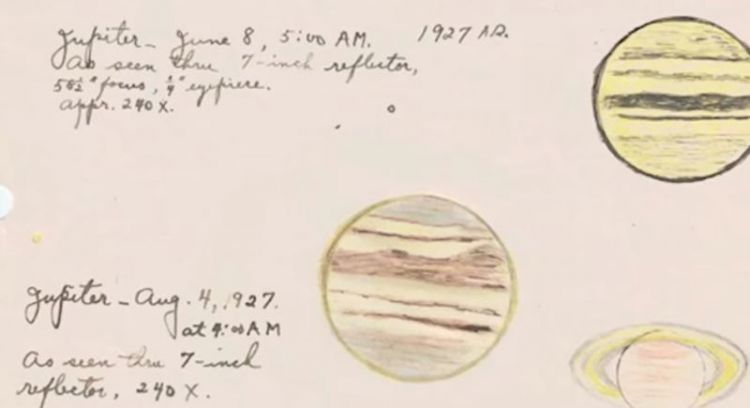

Tombaugh stayed up most nights looking through his homemade telescopes. He spent a whole night craning his neck back and forth between the telescope and a drawing pad, meticulously sketching out the details of the surfaces of Jupiter and Mars.

Some of Clyde Tombaugh’s early planet sketches. Source: Business Insider

He sent the drawings to the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, hoping the astronomers there would give him advice on how to build a better telescope. Instead, they offered him a job.

Lowell Observatory.

Tombaugh headed to the Lowell Observatory in 1929 with just a high school degree, a few belongings, and a keen eye.

Source: Pluto Safari

Percival Lowell. Source: Wikipedia

Before Tombaugh’s arrival, famed astronomer Percival Lowell had spent years at the observatory looking for the mysterious “Planet X.” Lowell knew there was something on the outskirts of our solar system, but he couldn’t seem to pinpoint the proof.

Tombaugh’s persistence and attention to detail brought the science fiction of Planet X into the light of scientific discovery. Residuals, the meager irregularities of Uranus and Neptune’s orbits due to the gravitational pull of another celestial body, indicated the existence of a large mass nearby–only a small blip on a map of stars.

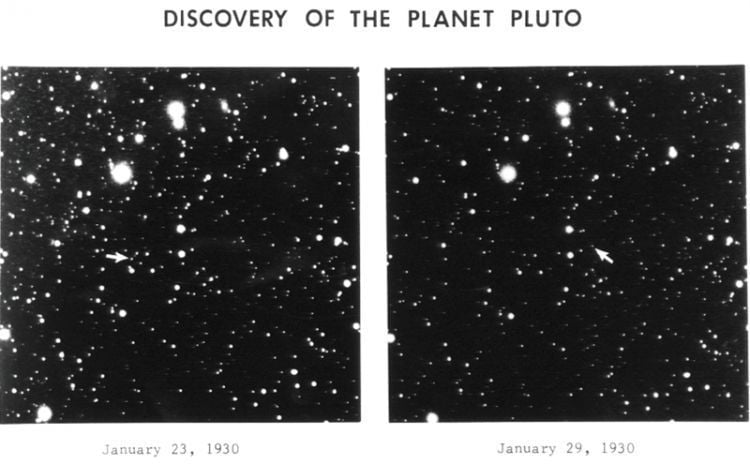

Using a blink comparator, Tombaugh compared photographic plates of the night sky taken several days apart. The device allowed him to alternate between plates to see if any noticeable change in the star pattern had occurred.

A large mass that appeared to jump a significant distance between plates would be one that was much closer to earth than the rest of the stars on the plate. That is, it could very well be a large, previously unidentified mass within our own solar system: most likely a planet. Tombaugh eventually spotted one such mass and, within moments, he knew he had made a tremendous discovery.

After confirming his observations with the analysis of a third plate, Tombaugh went and told the assistant director across the hall. The director came up and had a look, and everyone was in awe.

The two photographs that allowed Clyde Tombaugh to discover Pluto on February 18, 1930. Source: Wikimedia

Because this new dark planet was farthest from the sun, it was named Pluto, after the god of the underworld.

The suggestion came from Venetia Burney, an eleven-year-old girl from England, whose father, an employee of Oxford University, had the connections to get his granddaughter’s suggestion into the right hands. Coincidentally, as well, the first two letters of Pluto also made out the initials of of Percival Lowell, the founder of the observatory. The name was a perfect fit for the new planet.

Source: City of Las Cruces

Tombaugh’s discovery secured him a steady job at the observatory for the next 16 years, and a scholarship to the University of Kansas so that he could earn the degree he never had the chance to earn before. While there, he wanted to take beginner’s astronomy, but the professor wouldn’t let him, seeing it unfit for someone who had discovered a planet.

Tombaugh got his bachelor’s degree in astronomy in 1936 and his master’s in 1938, working at the observatory in the summers, and returning there full time soon after obtaining his master’s.

Back at Lowell, he made dozens of discoveries: asteroids, comets, star clusters, and even a supercluster of galaxies.

After WWII—during which Tombaugh taught navigation to U.S. Navy personnel—Lowell had to let him go. A shortage of funds left Tombaugh without a job, and so began his nine-year career in ballistics research for the military at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico.

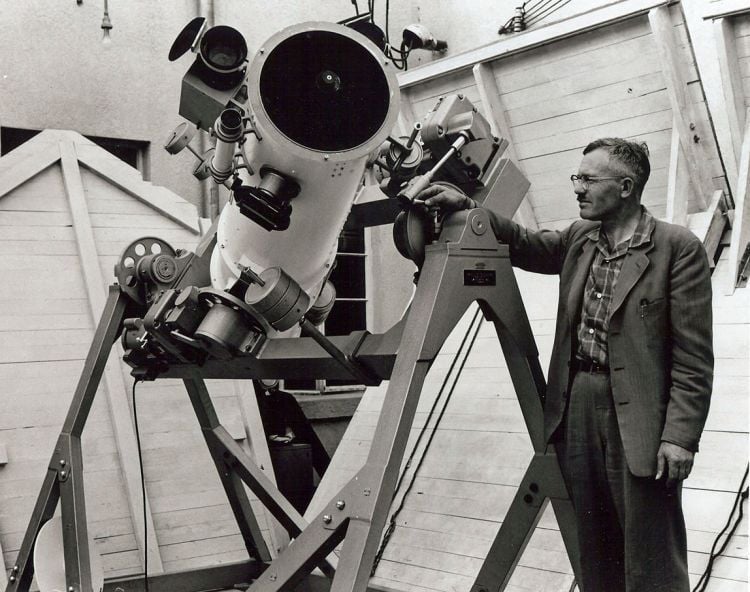

Tombaugh always knew how to make an impression. At White Sands, he designed the super camera IGOR (Intercept Ground Optical Recorder), which tracked the movements of rockets as they soared through the skies. This device was used for 30 years before new technology overtook it.

The IGOR tracking telescope.

Tombaugh never stopped working. In 1955, he joined the faculty of New Mexico State University where he taught astronomy for almost 18 years.

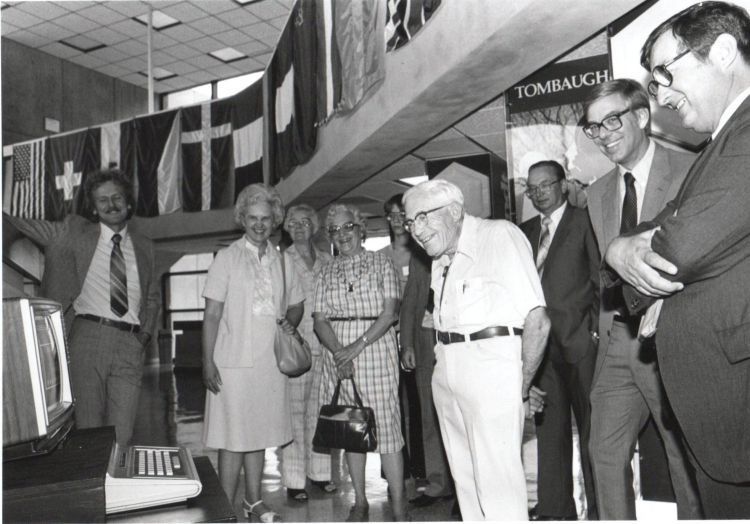

Clyde Tombaugh (center) being inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in New Mexico in 1980. Source: Etsy

Source: Chicago Tribune

In 1992, 19 years after Tombaugh retired and 62 years after he discovered Pluto, Robert Staehle, from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, called Tombaugh to ask him for permission to explore his planet. Tombaugh gave him the go ahead, while later remarking that it would be “one long, cold trip.”

Staehle’s phone call unleashed a series of events that culminated in the announcement of the New Horizons mission. Staehle’s persistence and the dedication of an eager team sparked the creation of a preliminary mockup spacecraft, Pluto Fast Flyby (PFF). The early models eventually led to an increased interest in the idea, and with the discovery of KBO’s beyond Pluto, the plan for Pluto’s exploration was set in stone.

Clyde Tombaugh passed away on January 17th, 1997 in his home in Las Cruces, New Mexico. Before his passing, he requested his ashes be sent into space. A small, inscribed container holding his ashes was attached to the bottom of New Horizons upon its completion.

This canister mounted on the New Horizons contains a small amount of Clyde Tombaugh’s ashes per his request. Source: Business Insider

Clyde Tombaugh’s life revolved around exploration. Now, he’s billions of miles away from Earth exploring the new frontier and discovering new horizons.

A NASA simulation of the New Horizons. Source: NASA

“I always wanted to reach out and extend my horizons. I always wanted to know what’s on the other side of the mountain. Never got over that.” – Clyde Tombaugh