Oluale Kossola, or Cudjo Lewis, was abducted by illegal slavers in 1860 and enslaved in Alabama, where he later began a self-contained African community once he was freed.

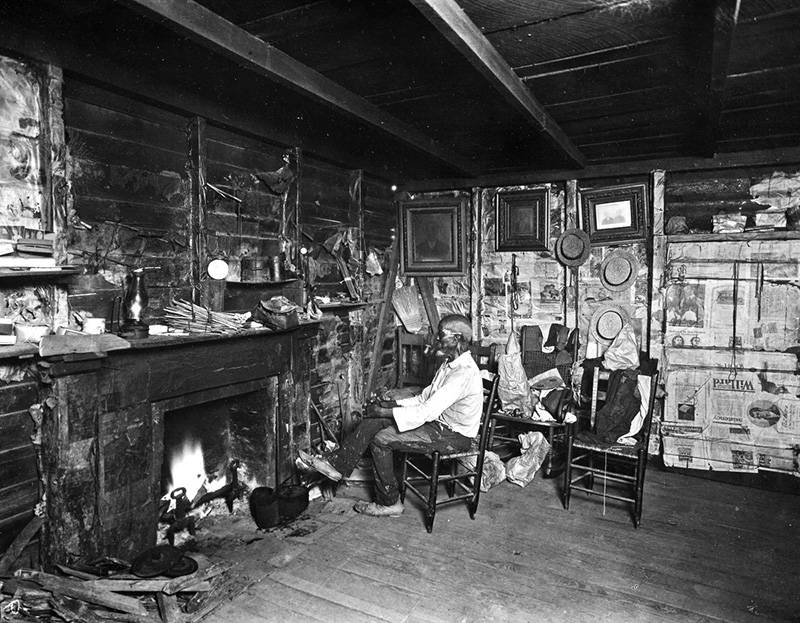

University of South AlabamaCudjo Lewis at his home in Africatown, which was a West African settlement based in Mobile, Alabama.

Over the course of nearly 400 years, more than 12 million Africans were abducted by slavers and shipped to Europe and North America. The process, known as the Transatlantic Slave Trade, was legally outlawed in the United States in 1807, but in 1860, one slaver violated that law — and shipped about 160 West African captives to Mobile, Alabama.

Among them was Kossola “Cudjo” Lewis, who is now known as one of the last known survivors of the Transatlantic slave trade. In 1927, Lewis was famously interviewed and filmed by author Zora Neale Hurston about his traumatizing experience as a slave and his attempt to recreate his West African homeland in Mobile.

He is considered the “only known African deported through the slave trade whose moving image exists,” and his story illuminated to Americans the full cruel story of the Transatlantic slave trade.

Cudjo Lewis Was Sold Into Slavery By A West African King

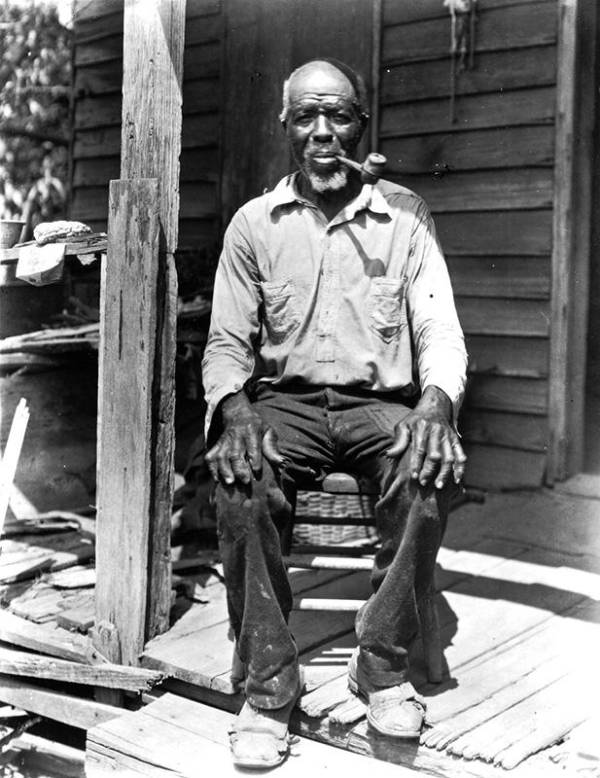

University of South AlabamaCudjo Lewis lived to the ripe old age of 95, making him the last-known man forced into slavery when he died in 1935.

Cudjo Lewis was born Oluale Kossola in 1841 in the Banté region of West Africa that is today encompassed by the nation of Benin. He grew up in a Yoruba community in a large family of 17 siblings.

In the spring of 1860, Kossola’s peaceful life was interrupted when he was abducted by the army of the African Kingdom of Dahomey and sold by them to slavers at the port Ouidah.

By this time, the importation of slaves had been illegal in the United States for nearly 60 years, and British and American ships had already set up a blockade around West Africa to prevent slavers from kidnapping any more people.

However, slave traders still attempted to illegally bring slaves to the United States due to the immense profit they stood to make by flouting the law. Furthermore, at that time, slave traders who had been charged with piracy were acquitted by a jury in Georgia, leading many to believe they could smuggle slaves into the U.S. without consequences.

Kossola was consequently sold to Captain William Foster of the Clotilda, the last slave ship to dock in the United States. Aboard were 115 to 160 more African men and women forced across the Atlantic to Mobile, Alabama.

Lewis Endures Four Years Of Slavery

When Kossola and the other captors arrived in Alabama, they were sold to businessman Timothy Meaher. Though Meaher was charged with the illegal possession of captives, by the time the authorities arrived on his property to execute his arrest, he had hidden away his captives and had erased all trace of them having been there.

Meaher was able to conceal over 100 slaves because he owned an area of land outside Mobile called Magazine Point which was surrounded by swamp and only easily accessible by boat.

Without the physical evidence of the captives, the case was dismissed in January 1861, and Cudjo Lewis and his fellow captives were forced to work on Meaher’s mill and shipyard as slaves.

For the next four years, Kossola toiled as a slave and was renamed “Cudjo,” a name given by the Fon and Ewe peoples of West Africa. Meaher was also simply unable to pronounce “Kossola.” Kossola’s new last name, “Lewis,” was likely derived from his father’s name, Oluale.

In 1863, slavery was made illegal through Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, and five years later, the passage of the 14th Amendment made all former slaves American citizens, but Cudjo Lewis was not included as he was not born in the United States. It was only months later when Lewis was nationalized that he became an American citizen.

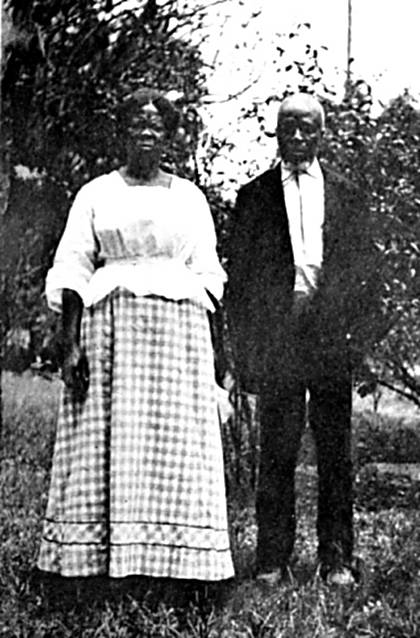

Wikimedia CommonsCudjo Lewis with Abache, another survivor of the Clotilda.

Following the end of legal chattel slavery in the United States, Cudjo Lewis met a young woman named Abile who also had been on the Clotilda. Together with many other freed Africans, they attempted to raise enough money for a voyage back home to their respective communities.

However, with the few economic opportunities afforded to former slaves in the South, many found that it would be impossible for them to raise enough money to return home. Cudjo Lewis decided that if he couldn’t go home, then he’d create a new one right there in the South.

Cudjo Lewis Creates A Home Away From Home In Africatown, Alabama

Like many freed slaves, Cudjo Lewis continued to work for the family to whom he once belonged for meager pay after his emancipation. Lewis took a job in Meaher’s lumber mill, where he eventually raised enough money to buy a two-acre plot of land in Magazine Point for $100 in 1872.

At this point, many of the Africans brought over on the Clotilda began to band together and buy out land in the area in order to create a self-contained community. Here, they spoke their regional African languages and partook in traditions that may have otherwise stayed lost to them back home. To outsiders, this area became known as Africatown.

While they continued practicing most of their West African traditions, many in Africatown did adopt Christianity and built a church. The community took a chief, named Charlie Poteet, and a medicine man, who went by Jabez.

Cudjo Lewis officially married Abile in 1880, and the two of them lived on their land, which Cudjo Lewis farmed and organized like a Yoruba family compound. They had two sons together, one of who continued to live in a house on Cudjo’s property when he married and started a family, in typical Yoruba fashion.

Even when his son died in 1908, Cudjo Lewis allowed his daughter-in-law and grandchildren, and eventually her second husband, to continue to live on his compound.

Cudjo worked as a farmer and a laborer to provide for his family until he was injured when his buggy was hit by a train in 1902. After that, he became the caretaker of the community’s Baptist church.

In the 1910s, a writer from Mobile name Emma Langdon Roche interviewed Cudjo for her book Historic Sketches of the South. As one of the few remaining ex-slaves who had actually endured the horrors of the transatlantic journey, and who had memories of their lives in Africa, Cudjo’s story became a sensation within the tight-knit community of anthropological writers at the time.

By the time pioneering American author and folklorist Zora Neale Hurston met him, Cudjo Lewis was already known as one of the last survivors of the Clotilda, and with the exception of a woman who died in 1940, the last person alive to have been brought to America from Africa as a slave.

Cudjo Lewis died on July 17, 1935, at the age of 95, outliving his wife and all of his children by 27 years.

His life is an intimate look at the horrors of the slave trade and how the process was a cultural genocide to the traditions of those forced to the United States from Africa. Despite the efforts of slave-era America to stamp out his heritage, Cudjo Lewis continued to live by his born traditions and create a flourishing community in a country that wanted to erase it.

Enjoy this article on Cudjo Lewis, the last slave brought to the United States? Next, read the story of the slave who escaped George Washington’s estate. Then, see footage of a modern-day African slave market that sparked outrage around the world.