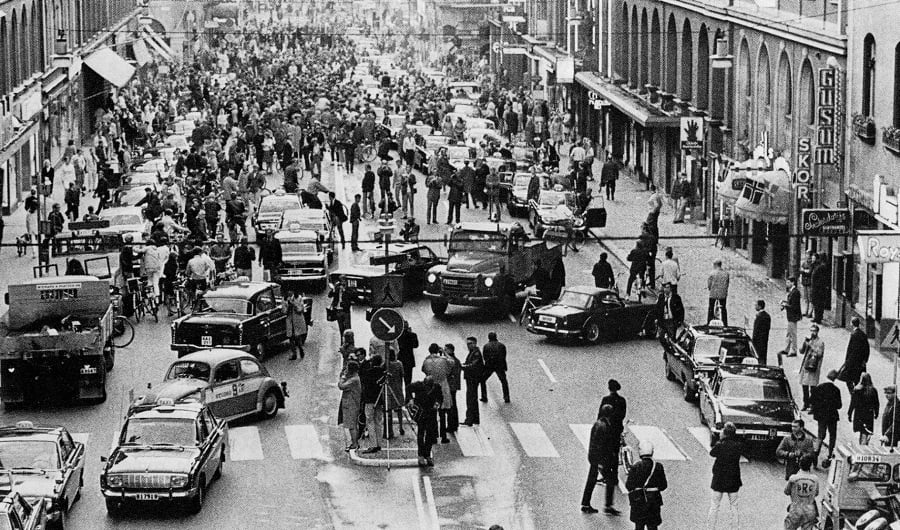

On Dagen H, the day Sweden switched its driving lane from the left to the right, chaos ensued — and the cost of the change was staggering.

Nobody likes change. Take, for example, Sweden’s Dagen H on September 3, 1967, when all of Sweden’s drivers had to make a simultaneous switch from driving on the left side of the road to the right.

This certainly wasn’t an easy switch to make, but if anyone can be counted on for organization and planning, it’s the nation that gave the world Ikea. The government hired psychiatrists to speak with citizens about their fears and concerns. A massive PR campaign raised awareness. Specially commissioned songs, clothing, and billboards were used to spread the message. Men were walking the streets wearing shorts with a giant “H” on the butt (for “Dagen H”), and signs with the date of the switch plastered public spaces.

The cost to the government for all this? A whopping $120 million, which amounts to somewhere around $930 million in today’s dollars.

Exactly why the Swedish had previously chosen to drive on the left isn’t completely clear. One theory connects it all the way back to the common use of right-handed swords (which would be more usable, when driving, if one were in the left lane). But whatever the reason, in common practice, horse and buggies had ruled Sweden’s left lane since at least 1734. The left then became the law in 1916.

But as soon after as 1920, the Swedish parliament started arguing that maybe using the left lane law wasn’t the brightest move — most of Europe was already driving in the right lane. The government continued to debate a switch until 1939, when an Austrian man with dreams of world domination and more than a few medical abnormalities gave Sweden’s leaders more pressing concerns.

The debate between right and left then resumed in 1955 with a nationwide referendum. But, remember, nobody likes change: 83 percent the Swedish population said they were against switching to the right side of the road. It took the work of lobbyists to convince the government to go against the tide of public opinion in 1963. The government then set a date to give the people (and their aggressive PR campaign) plenty of time: September 3, 1967.

Perhaps the most striking part of this whole story is that, despite the photo above, Dagen H was largely a success. Thanks to a driving ban on non-essential traffic until 5 AM and civilian drivers being kept off the road until the evening, there were actually less automobile accidents than normal on Dagen H.

However, Alec Dunic, a visiting British traffic expert, wasn’t too optimistic: “We have only seen the bride and groom brought to the altar,” he told the AP. “The citizens of Sweden have now embarked on their honeymoon.”

Automobile accidents rose back up to normal levels six weeks after Dagen H and remained consistent with the rates before the switch thereafter. While the switch may have been a wash, in terms of safety, the massive PR campaign remains a stunning testament to what it truly takes to fight the fact that nobody likes change.