Before he became a Civil War general, Congressman Dan E. Sickles' scandalous murder trial changed our legal system forever.

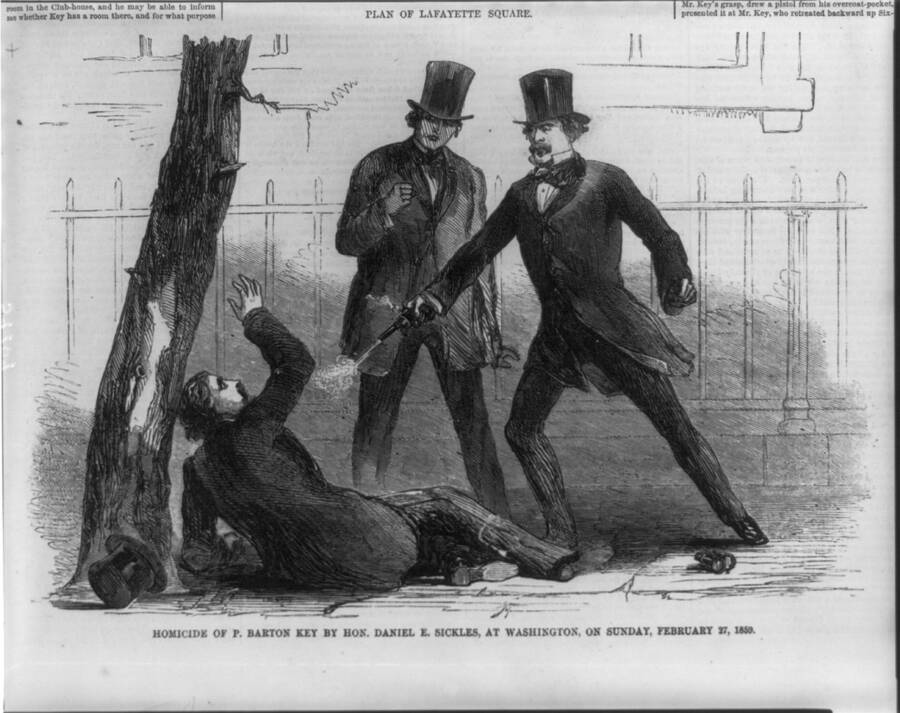

Harper’s Weekly/Library of CongressAn illustration of Daniel Sickles shooting Barton Key appeared in Harper’s Weekly.

In 1859, Congressman Dan Sickles pulled out a pistol and shot his wife’s lover. Standing in full view of the White House, Sickles screamed, “You scoundrel, you have dishonored my house — you must die!”

The shocking crime made headlines around the world, and Sickles became the first person in American history to plead temporary insanity to get away with murder.

The Affair That Sparked A Murder

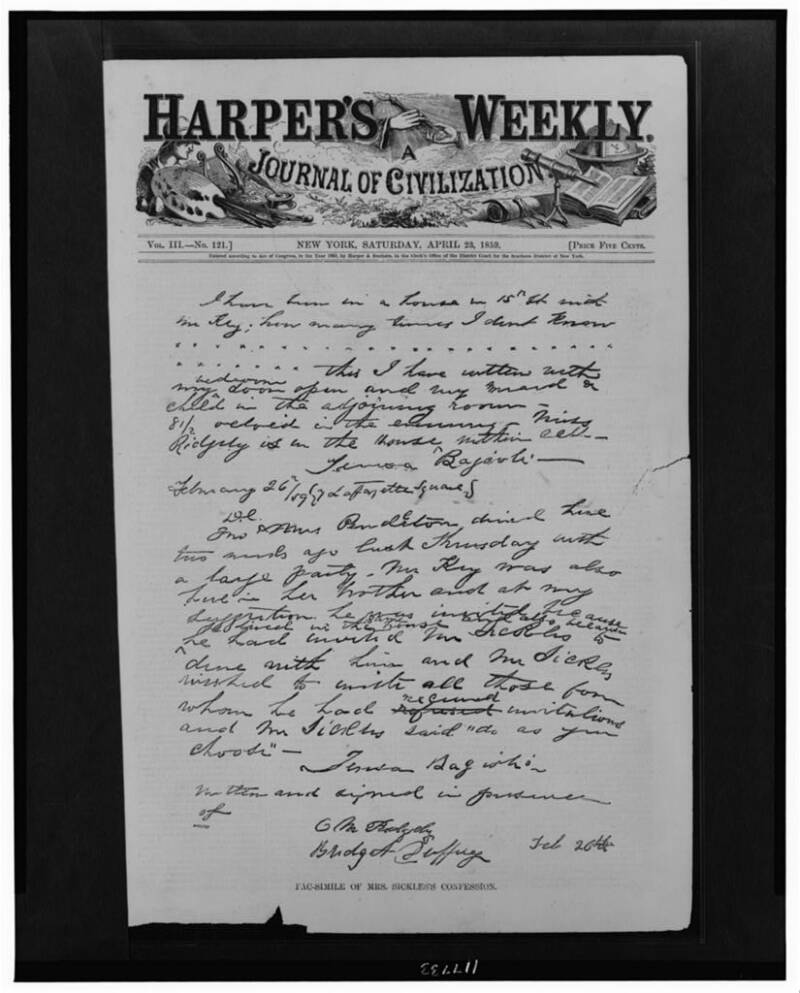

Harper’s Weekly/Library of CongressDan Sickles pressed Teresa to write out a confession after he learned of the affair.

The son of a wealthy New York family, Dan Sickles earned a law degree and seduced a teenager before he was elected to Congress.

Sickles was 33 when he married 16-year-old Teresa Bagioli. When he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1856, the couple took Washington, D.C. by storm, becoming fixtures in high society.

Both Dan and Teresa pursued affairs. Dan also had a reputation for visiting brothels – but only Teresa’s dalliance raised eyebrows.

In the 19th century, a wife’s affair transformed her husband into a cuckold, undermining his masculinity, while a husband’s affairs were simply business as usual.

According to Dan Sickles, Teresa’s affair drove him to murder.

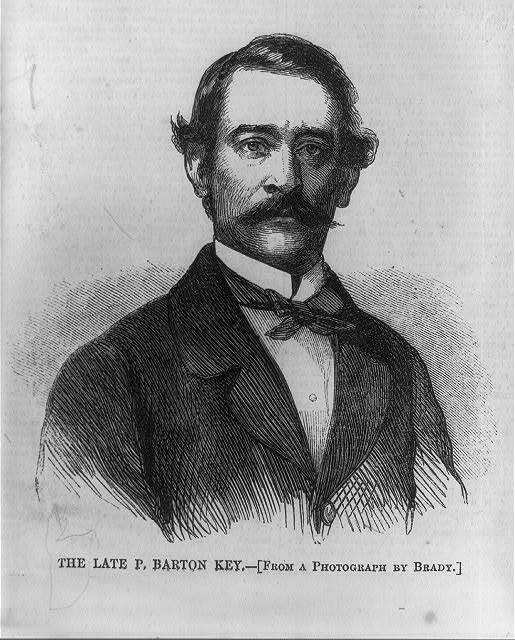

Beginning in the spring of 1858, Teresa carried on an affair with Barton Key, a close friend of Congressman Sickles and the son of Francis Scott Key who penned the lyrics to “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Library of CongressPortrait of Barton Key, known as “the handsomest man in all Washington society.”

One D.C. gossip columnist called Key “the handsomest man in all Washington society.”

Key signaled Teresa by waving his pocket-handkerchief on the street. The pair would meet at an abandoned house only steps from the White House, where Teresa confessed, “I did what is usual for a wicked woman to do.”

Everything changed on Feb. 24, 1859, when Sickles received an anonymous letter. The enraged congressman confronted Teresa and forced her to write a confession.

Three days later, Sickles spotted Key outside his home, waving his handkerchief to signal Teresa. “That villain is out there now making signs,” Sickles raged. Grabbing three guns, Sickles rushed out to confront Key.

Sickles fired his pistol before Key could say a word. Key threw a pair of opera glasses at Sickles and tried to hide behind a tree, but Sickles continued to fire until a bystander wrestled him to the ground.

Sickles had gunned down Key in Lafayette Park on a sunny Sunday afternoon. With no chance of escape, Sickles took a carriage to the home of Attorney General Jeremiah S. Black where he surrendered.

The Media Firestorm

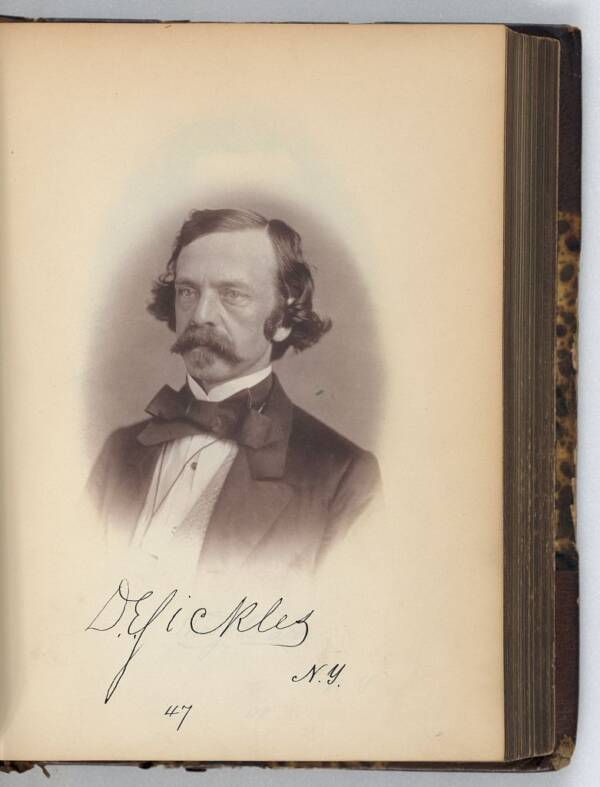

Julian Vannerson/Library of CongressA portrait of Congressman Dan Sickles from the year he shot Barton Key.

The sensational murder became front-page news.

“The tragic affair produced a great sensation,” reported the New York Herald. “In the streets, the law courts, public houses, private dwellings, and, in fact, everywhere, it was the prominent topic of conversation.”

Even President James Buchanan took sides in the sensational case. He sent a letter of support to the imprisoned congressman.

From jail, Sickles gave interviews with the press. “He has dishonored me, and we could not live together on the same planet,” Sickles told one paper.

Harper’s Weekly judged the outcome before the trial began. “The public of the United States will justify him in killing the man who dishonored his bed.”

Dan Sickles, who admitted firing the shots that killed Key, hoped the jury would agree.

The Trial of Dan Sickles

Harper’s Weekly/Wikimedia CommonsTeresa Bagioli Sickles stayed with her husband after the trial.

Congressman Dan Sickles hired eight defense attorneys to represent him during his trial. One of them, John Graham, spent a full two days on his opening statement defending Sickles.

Adultery was evil, Graham intoned, quoting Shakespeare’s Othello to justify Sickles’s actions. Discovering the affair had made Sickles temporarily insane.

Temporary insanity was a new concept in American courts. While defendants had pleaded insanity before, no one had claimed to be insane only temporarily.

But Graham relied on the jury’s sympathy toward Sickles to justify the murder. “It may be tragical to shed human blood; but I will always maintain that there is no tragedy about slaying the adulterer,” Graham argued.

The trial also painted Teresa Sickles as a prostitute and murderer.

A wife who “surrendered to the adulterer” longed for her own husband’s death, one defense attorney argued, either “by the cup of the poisoner or the dagger or pistol of the assassin.”

Another attorney added that the affair pulled Teresa toward “the horrid filth that is common prostitution.”

Dan Sickles painted himself as “the avenger of the invaded household.” His wife was an immoral woman. And Key deserved to die.

The Verdict

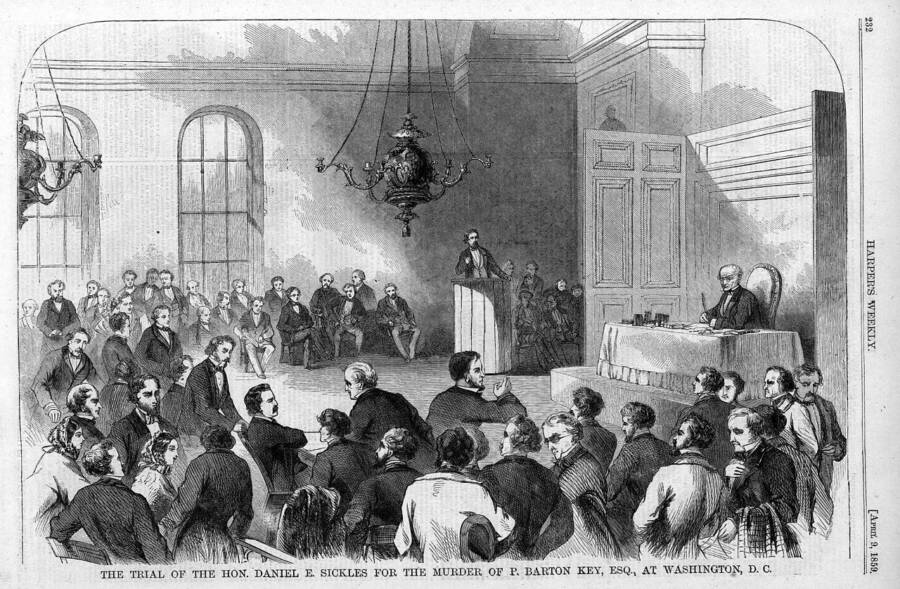

Unknown/Library of CongressThe courtroom during the murder trial of Dan Sickles.

Was the murder of Key justifiable homicide or temporary insanity? Dan Sickles’s attorneys argued both at the same time.

The presiding judge didn’t put much stock in the temporary insanity defense. In his jury instructions on April 26, Judge Crawford warned the jurors that a gap between Sickles learning of the affair and killing Keys weighed the scales toward premeditated murder – and, in fact, Sickles had spent three days plotting his revenge after receiving the anonymous note.

Yet it only took the jury an hour to declare Dan Sickles not guilty by reason of temporary insanity.

The packed courtroom burst into applause and 1,500 people led Sickles through the streets in an impromptu victory parade.

From the start, many predicted Sickles would walk for his crime. During jury selection, 72 of the first 75 prospective jurors were excused for sympathizing with the murderer.

“We regard this as a most mistaken and most mischievous verdict,” declared the Tribune. “It is a verdict which carries this country a long stride backward toward the age when Might was Right, and all wrongs were redressed by the red hand, or not at all.”

Dan Sickles After The Trial

Unknown/Library of Congress

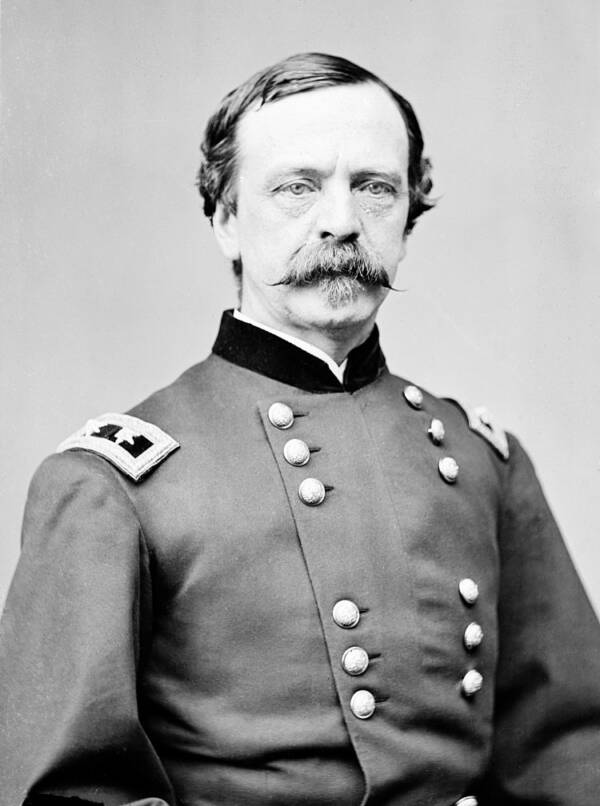

After his acquittal, Dan Sickles became a Civil War general.

The trial turned Dan Sickles into a nationally known figure. But his actions after the trial kept Sickles in the headlines for decades.

Shortly after his acquittal, Sickles and his wife Teresa publicly reconciled, drawing criticism from their peers in Washington and in the press.

“We hope the sympathizers with Mr. Sickles at Washington, and especially the jury who exalted him into a great champion of the sanctity of marital relations will be satisfied with this result,” the Baltimore American wrote.

Next, Sickles left his congressional seat in 1860, quickly turning around to raise a brigade of men for the Civil War. As a general, Sickles led troops at Gettysburg, where he ignored his superior officer’s orders and lost a leg to a cannonball.

Library of CongressAfter the trial, Dan Sickles went on to become a Civil War general who fought at Gettysburg and died in 1914.

As an ambassador to Spain after the war, Sickles seduced the Queen, and in his final years, Sickles was accused of stealing public funds.

The legacy of Dan Sickles’s trial outlived Sickles himself. While his case represents the first successful temporary insanity plea, the jury almost certainly didn’t buy that defense.

Instead, Victorian moralists decided that Key had it coming. Even a notorious philanderer like Sickles could claim righteousness if cuckolded.

Yet even though Dan Sickles’s trial says more about 19th-century views of masculinity and women’s sexuality, the ruling still broke new legal ground. In the past 150 years, the temporary insanity defense has become a mainstay in the American legal system.

Dan Sickles was the first to argue temporary insanity, but he wasn’t the last. Learn more about how Lorena Bobbitt and Charles Manson’s henchman Tex Watson claimed temporary insanity.