De-Extinction: The Why…And Why Not

Some claim that conservationist efforts, like those that fight deforestation (above, in Brazil), could suffer if time and resources are allocated to de-exinction efforts. Image Source: WIRED

Besides suggesting we owe it to the endangered and extinct species, advocates for de-extinction say we should delve into de-extinction as a means to preserve biodiversity, restore diminishing ecosystems, and improve the science of preventing extinctions.

In an article he wrote for National Geographic, Stewart Brand (president of the Long Now Foundation, a nonprofit that addresses extremely long-term cultural and societal issues, like the Year 10,000 Problem) discusses the need for de-extinction research.

We could, Brand says, reverse what we thought was irreversible and allow the current generation of children to experience a great return of extinct species, possibly altering their perceptions of the natural world. De-extinction zoos will inevitably become wildly popular, Brand claims, helping to raise awareness and fund conservation efforts. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, he claims that de-extinction will allow us to repent for our wrongdoings.

A boy touches a mammoth carcass outside the Shemanovsky Museum in Russia.

Furthermore, Brand and other advocates believe that further examination of genomes will provide us with useful information that will help detect genetic weakness and allow for the prevention of the extinction in species currently plagued by disease.

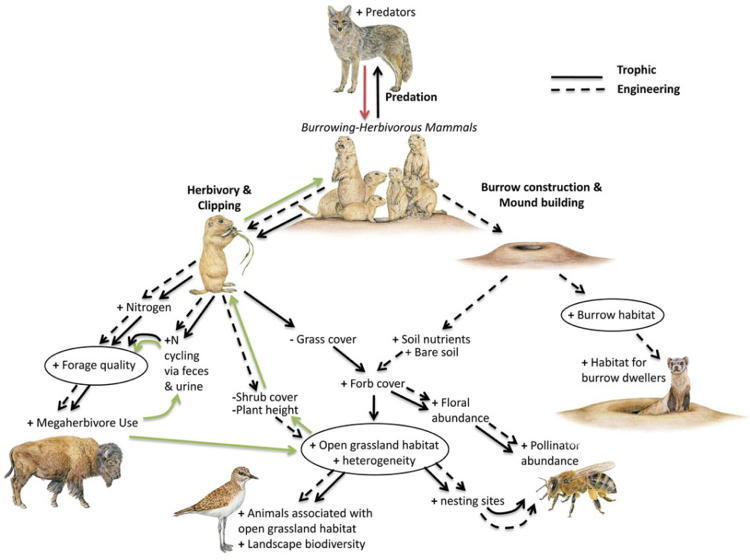

In addition, if successful, resurrecting “keystone” species could also restore the ecosystems from which they came, which would in turn help the extant species currently occupying those ecosystems.

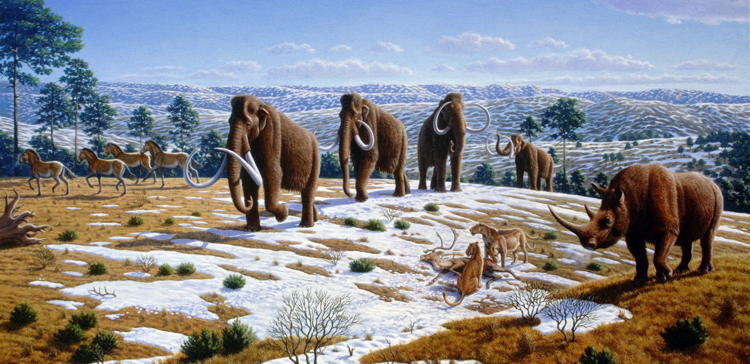

Certain species indeed have disproportionately huge roles in maintaining the ecological richness of their ecosystems. Woolly mammoths, for instance, were the dominant herbivore of the “mammoth steppe,” previously the largest biome on earth.

Since their demise, the grasslands they helped sustain have reverted to tundras and boreal forests. The woolly mammoths’ presence would hypothetically restore those ecosystems, returning carbon-fixing grass and reducing emissions of greenhouse gases in the thawing tundra.

An artist’s rendering of the mammoth steppe. Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

Many, however, don’t agree with Brand’s positive outlook on de-extinction science. Paul R. Ehrlich, a professor of population studies at Stanford University, wrote a spirited paper against de-extinction. Setting aside the question of whether or not the process is even practical, Ehrlich states that it is a misallocation of effort and resources. All available resources, he claims, should be put into conservation and preventing extinctions of current species by halting their causes, such as habitat destruction, climate change, pollution, and over-harvesting. He argues that the reintroduction of a few long-gone species is of little use to us at this point.

Ehrlich also addresses the issue of “moral hazard.” Coined by economists, this term refers to situations in which a person becomes more willing to take risks because the potential cost will be partly burdened by another party. In the case of de-extinction, the argument is that if people know we can resurrect species, then less will be done to stop mass extinction.

The mutually dependent relationships that make up a typical ecosystem. Image Source: environmentalstudiesblog.wordpress.com

Ehrlich also notes that we are, dangerously, thinking in terms of species, rather than species populations. Animal populations contribute to the biodiversity of their ecosystem and provide crucial services within that ecosystem. Obviously, as more populations disappear, the entire species becomes more rare.

But, at the point at which an entire species becomes endangered, their specific ecosystems have already been damaged by the decreased populations and, unless the populations can be reintroduced in sufficiently large numbers, the small populations of an endangered, or even resurrected, species holds little value for its ecosystems.

Finally, and unsurprisingly, the moral issues behind being genetic puppet masters and our eternal fear, and love, of playing God must be considered. There is a consistent pattern of public unease with the advancement of genetic science. As our understanding of the genome gets better, we’ll have more and more chances to alter it, for animals and humans alike.

At this point, we have the ability to read and manipulate DNA. It is no longer a question of whether or not we can. The questions now are if we should take on this power, and what consequences, if any, will be awaiting us on the other side.