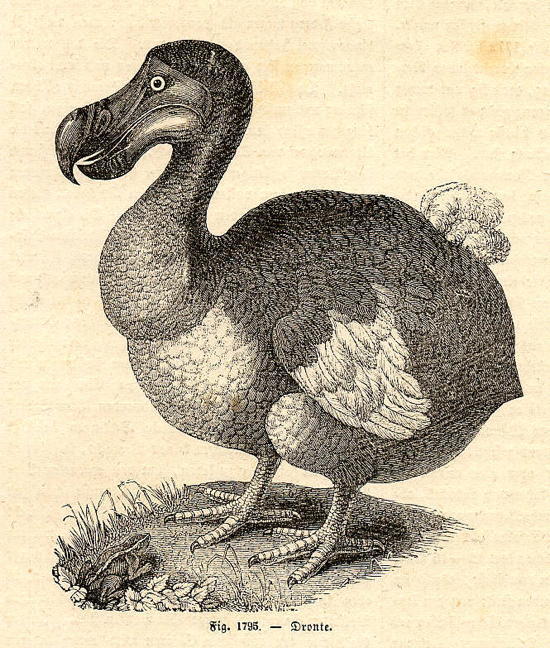

In 1598, the Dutch landed on the island of Mauritius, just off the coast of Madagascar in the Indian Ocean. Here, they were met by a massive population of flightless, naive, meaty birds. Salivating, the sailors happily began killing them, kindly bestowing the name “dodo” upon the shell-shocked animals. Over the next several decades, humans, and the rats, pigs, monkeys and other animals they brought with them, made short work of the small island and the entire species of the dodo, rendering it extinct by 1662.

This isn’t exactly a unique story, as far as extinction goes. Colonizers move in, and the indigenous animal (as well as human and plant) populations begin to dwindle. But, what if we could apologize for our pillaging ways and resurrect these extinct species?

De-Extinction: The How

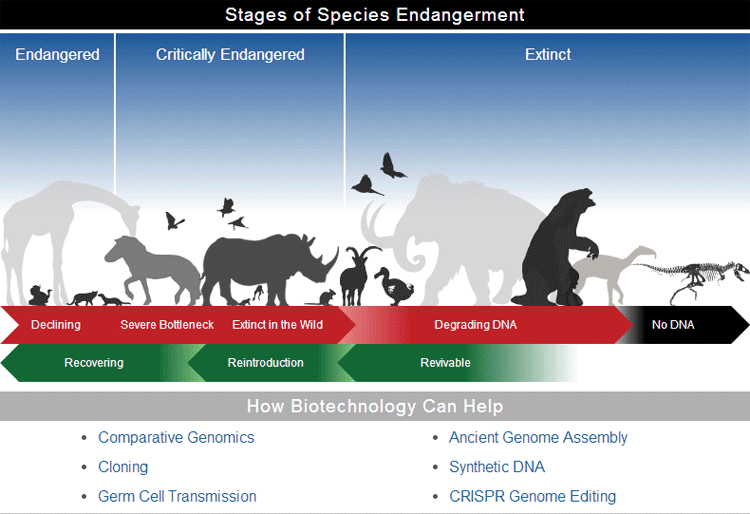

Image Source: The Long Now Foundation

De-extinction, or resurrection biology, is the process of bringing an extinct species back to life. And it’s now a reality. The process involves several lengthy and sophisticated procedures including gene transfer, interspecies cloning, and surrogate birthing and parenting, all of which, have genetic engineers’ and biotechnicians’ toes tingling.

I know what you’re thinking: So, when do the gates to Jurassic Park/World/Universe open?

Unfortunately, I must put your (borderline bloodlust) dreams to an end. Viable DNA is needed to recreate a species. The oldest DNA sequence to date is about 700,000 years old. Also, even under the best conditions, DNA will only survive for 1.5 million years, and the dinosaurs went extinct 65 million years ago. Alas.

To resurrect a species from extinction, we must have a closely related living species and DNA from specimens and fossils of the extinct species. Then, genes can be transferred from the extinct species into the genome of the living relative. The outcome is the start of an interspecies clone, closely resembling the extinct animal. Creating healthy offspring will take countless attempts, but the technology is getting there.

De-Extinction: The Who

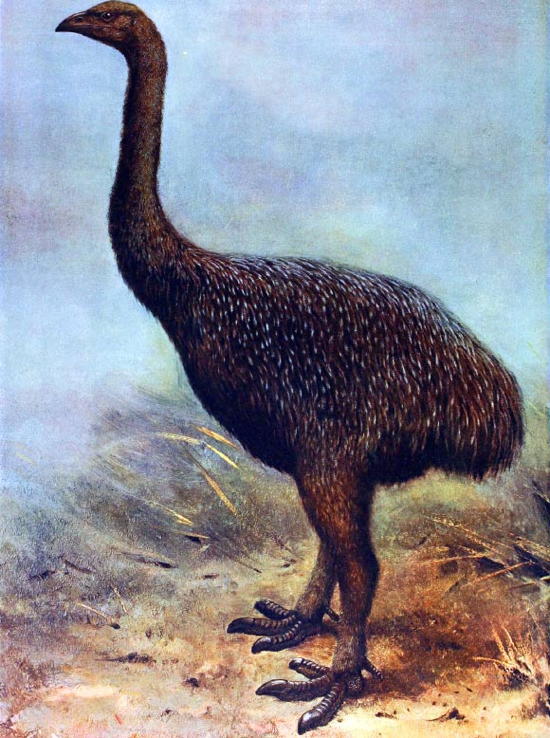

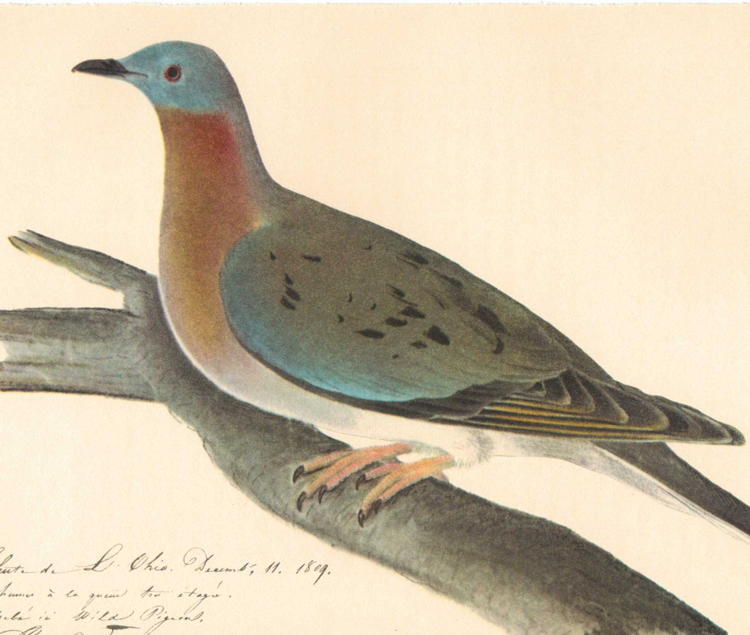

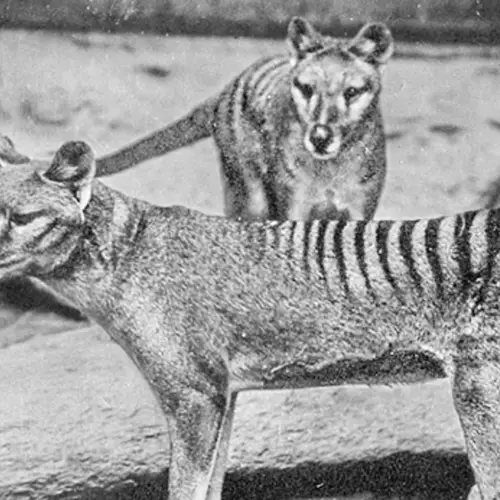

While dinosaurs are not eligible, there are still some great candidates up for de-extinction. Sitting at the top of the list are the dodo, woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros, passenger pigeon, gastric-brooding frog, Pyrenean ibex, Carolina parakeet, moa, and Tasmanian tiger.

DNA from all of these animals has been preserved and there are species living today which are genetically close enough to help create a complete genome and provide surrogacy. In the future, any of these species could possibly reach the ultimate goal of de-extinction research: they could become a naturally reproducing species, reintroduced into their former environment.

But why do this?