Physicists Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin both suffered agonizing deaths after making minor slips of the hand while working on the plutonium orb known as the "demon core" at Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

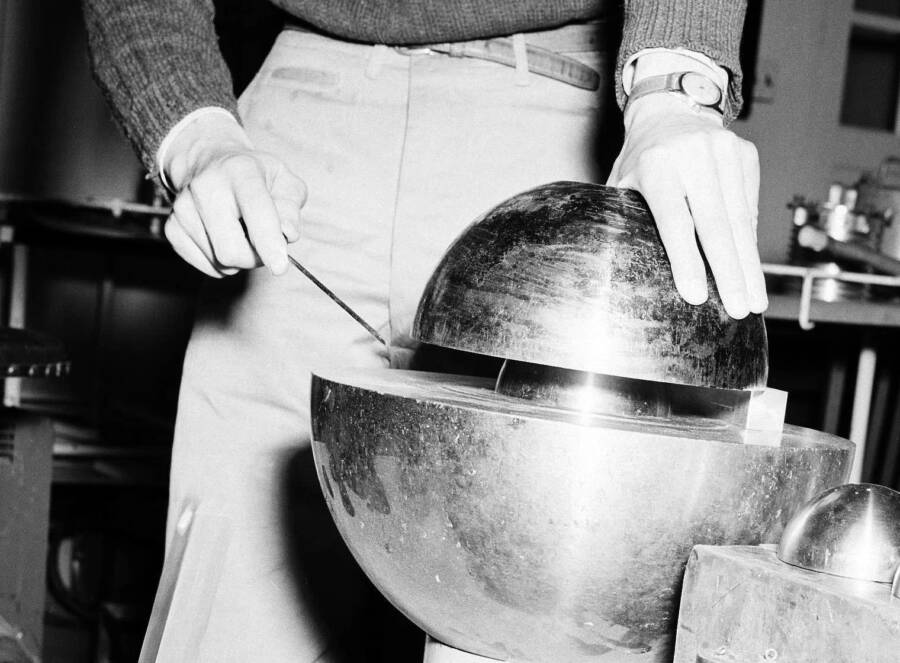

Los Alamos National LaboratoryA reconstruction of the 1946 experiment with the demon core that killed physicist Louis Slotin.

To the survivors of the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki near the close of World War II, these unprecedented explosions were nothing short of hell on earth. And though another plutonium core — meant for use in an atomic bomb if Japan didn’t surrender — was never deployed, it still managed to kill two scientists who were working on it at the Los Alamos laboratory in New Mexico. The excruciating circumstances of their deaths soon earned this orb the nickname “demon core.”

Both scientists, Louis Slotin and Harry Daghlian, were conducting similar experiments on the core, and both made eerily similar mistakes that proved fatal nine months apart in 1945 and 1946.

Before these fateful experiments, scientists had simply called the core “Rufus.”

But after these horrifying deaths, it needed a new name, and “demon core” was chilling enough to fit the bill. But what exactly happened to the two scientists who died while handling it?

The Heart Of A Nuclear Bomb

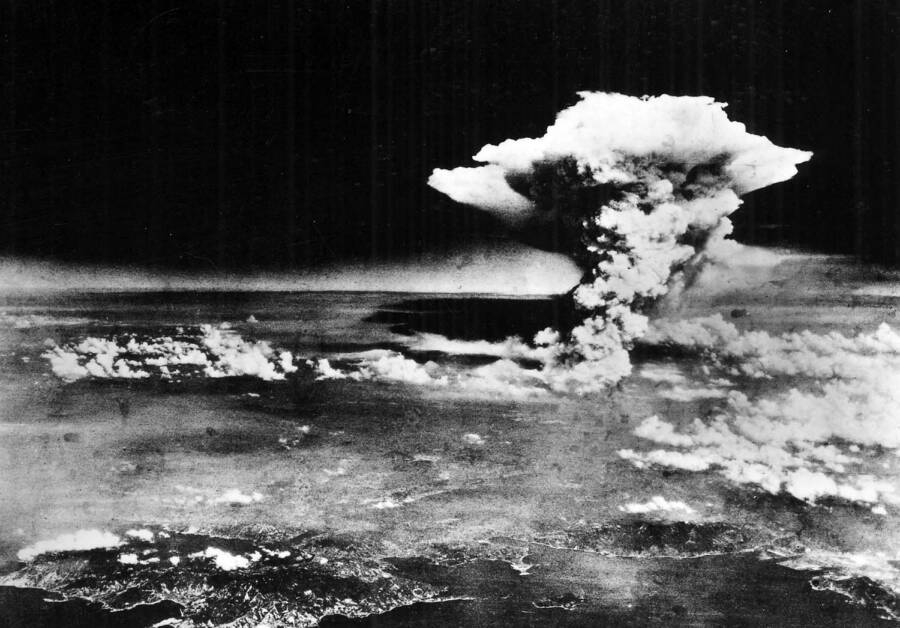

In the waning days of World War II, the United States dropped two nuclear bombs on Japan. One was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and one was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9. In case Japan didn’t surrender, the U.S. was prepared to drop a third bomb, powered by the plutonium core later called “demon core.”

It weighed almost 14 pounds and stretched about 3.5 inches in diameter. And when Japan announced its intention to surrender on August 15, scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory were allowed to keep the core for experiments.

The scientists wanted to test the limits of nuclear material. They knew that a nuclear bomb’s core went critical during a nuclear explosion, and wanted to better understand the limit between subcritical material and the much more dangerous radioactive critical state.

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty imagesAn aerial photo of a nuclear bomb exploding over Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945.

But such criticality experiments were dangerous — so dangerous that a physicist named Richard Feynman compared them to provoking a dangerous beast. He quipped in 1944 that the experiments were “like tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon.”

And like an angry dragon roused from slumber, demon core would soon kill two scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory when they got too close.

How The Demon Core Killed Two Scientists

Los Alamos National LaboratoryHarry Daghlian’s burnt and blistered hand after his experiment with the demon core went awry.

On August 21, 1945, about a week after Japan expressed its intention to surrender, Los Alamos physicist Harry Daghlian conducted a criticality experiment on demon core that would cost him his life. According to Science Alert, he ignored safety protocols and entered the lab alone — accompanied only by a security guard — and got to work.

Daghlian’s experiment involved surrounding the demon core with bricks made of tungsten carbide, which created a sort of boomerang effect for the neutrons shed by the core itself. Daghlian brought the demon core right to the edge of supercriticality but as he tried to remove one of the bricks, he accidentally dropped it on the plutonium sphere. It went supercritical and blasted him with neutron radiation.

Daghlian died 25 days later. Before his death, the physicist suffered from a burnt and blistered hand, nausea, and pain. He eventually fell into a coma and passed away at the age of 24.

Exactly nine months later, on May 21, 1946, demon core struck again. This time, Canadian physicist Louis Slotin was conducting a similar experiment in which he lowered a beryllium dome over the core to push it toward supercriticality. To ensure that the dome never entirely covered the core, Slotin used a screwdriver to maintain a small opening, though he had been warned about this method before.

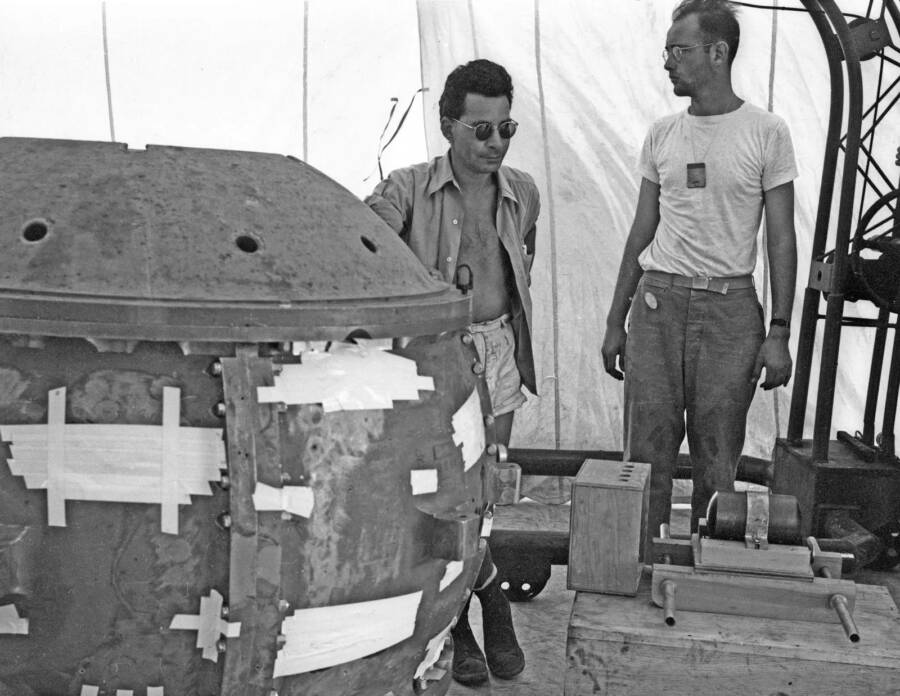

Los Alamos National LaboratoryLouis Slotin, left, wearing sunglasses, with the partially assembled first nuclear bomb.

But just like the tungsten carbide brick that had slipped out of Daghlian’s hand, Slotin’s screwdriver slipped out of his grip. The dome dropped and as the neutrons bounced back and forth, demon core went supercritical. Blue light and heat consumed Slotin and the seven other people in the lab.

“The blue flash was clearly visible in the room although it (the room) was well illuminated from the windows and possibly the overhead lights,” one of Slotin colleagues, Raemer Schreiber, recalled to the New Yorker. “The total duration of the flash could not have been more than a few tenths of a second. Slotin reacted very quickly in flipping the tamper piece off.”

Slotin may have reacted quickly, but he’d seen what happened to Daghlian. “Well,” he said, according to Schreiber, “that does it.”

Though the other people in the lab survived, Slotin had been doused with a fatal dose of radiation. The physicist’s hand turned blue and blistered, his white blood count plummeted, he suffered from nausea and abdominal pain, and internal radiation burns, and gradually become mentally confused. Nine days later, Slotin died at the age of 35.

Eerily, the core had killed both Daghlian and Slotin in similar ways. Both fatal incidents took place on a Tuesday, on the 21st of a month. Daghlian and Slotin even died in the same hospital room. Thus the core, previously codenamed “Rufus,” was nicknamed “demon core.”

What Happened To The Demon Core?

Los Alamos National LaboratoryA recreation of the Louis Slotin’s 1946 experiment with the demon core.

Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin’s deaths would forever change how scientists interacted with radioactive material. “Hands-on” experiments like the physicists had conducted were promptly banned. From that point on, researchers would handle radioactive material from a distance with remote controls.

So what happened to demon core, the unused heart of the third atomic bomb?

Researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory had planned to send it to Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands, where it would have been publicly detonated. But the core needed time to cool off after Slotin’s experiment, and when the third test at Bikini Atoll was canceled, plans for demon core changed.

After that, in the summer of 1946, the plutonium core was melted down to be used in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. Since the United States hasn’t, to date, dropped any more nuclear weapons, demon core remains unused.

But it retains a harrowing legacy. Not only was demon core meant to power a third nuclear weapon — a weapon destined to rain destruction and death on Japan — but it also killed two scientists who handled it in similar ways.

Was the plutonium core cursed, as other scientists darkly suggested by giving it a new nickname? Perhaps, perhaps not. What’s certain is that this strange footnote from U.S. history embodies the grave stakes that came with nuclear power, and the devastating consequences of “tickling the dragon.”

After reading about demon core and the scientists it killed, see how Hisashi Ouchi was kept alive for 83 excruciating days following a nuclear accident at Japan’s Tokaimura nuclear power plant in 1999. Then, read up on the Little Boy bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.